...Civil Rights traditions were passed on to the next generation

by words and actions.

The importation of enslaved Africans to the Americas--and the evolution of religion to validate the thoughts and procedures to nullify the humanity of Africans--has been massaged, dissected, discussed, homogenized, and ingested since the arrival of the African, both slave and free, into the worlds newly discovered by Europeans. From this dissected cacophony emerged the rules of engagement which focused on how to maintain the subjugation of this influx of humanity.

Through their solidarity and shared common experiences, the enslaved African would indeed save themselves and their cultures. They created a folklife.

While the importation of enslaved Africans and the economic evolution of the South, coupled with the industrialization of the North, remains somewhat of a romanticized and not fully explored conversation in some quarters, the more amazing and under-told story is that of the enslaved African. Surviving under the most inhumane conditions, the enslaved Africans gave birth to progeny who would become doctors, lawyers, business owners, educators, builders, inventors, judges, and presidents in a country which considered them less than human. The how of this deserves to be explored.

Now I realize that this may seem like old news to you but stay with me. The National Park Service Ethnography Program offers a snapshot of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. From 1519 to 1800, captured Africans were flung across the world by these carriers: Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain, the British Caribbean, the American colonies, Denmark, and Portugal. With the transition from tobacco to cotton in the Colonies, the economic benefits of the slave trade increased, and most of the slavers shipped their human cargo to the Americas.

The majority of the captured Africans came from the western region of Africa. These are just some of the countries which are included in this area: Senegambia (Senegal and Gambia), Sierra Leone, Gold Coast (Ashanti and the Fante states, known as Ghana, today), Old Calabar (Nigeria), West Central Africa (Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, et.al.) and Southeast Africa (Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe and more). These captured Africans, from so many countries, speaking a multitude of languages and clinging to their many customs, found themselves thrust together in the belly of a ship bound for a land they knew not where.

In the introduction to his book, The Half has never been Told, Edward D. Baptist writes:

Enslaved [Africans] chose many things. But perhaps most importantly, they chose survival, and true survival in such circumstances required solidarity. Solidarity allowed them to see their common experience, to light their own way by building a critique of enslavers’ power that was an alternative story about what things were and what they meant...For what enslaved people made together - new ties to each other, new ways of understanding their world – had the potential to help them survive in mind and body.

Through their solidarity and shared common experiences, the enslaved African would indeed save themselves and their cultures. They created a folklife.

In some form or the other, every society passes on their traditions, history, myths, and customs to each generation. Because of the extreme conditions in which the enslaved African was forced to live, they relied heavily on their African roots of passing on these traditions orally. By combining the art of storytelling with their demonstrated actions, the elders were able to pass on not only traditions, but survival techniques to each new generation, thereby ensuring their survival.

The modeling of behavioral courage by elders in adversarial situations, which is then exhibited in the actions of subsequent generations, we have termed “generational courage.”

Most people would like to believe that the Civil Rights movement arose out of the actions of the late 1950s and ‘60s. It was the result of generations of people of African descent, leading by example, preparing, and equipping each new generation for the challenges yet to come.

In his book I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, Charles Payne explores this very concept of the evolution of Black activism in Mississippi. As a part of his examination, Payne includes a quote by Erik Erikson which expresses the growth of clarity in each generation:

The values of any new generation do not spring full blown from their head: they are already there, inherent if not clearly articulated in the older generation.

This concept is further underscored in Payne’s interview with the Reverend Aaron Johnson:

“I think somehow you’ve always had families that were not afraid, but they had sense enough to hold their cool and they just talked to their immediate family and let them know, you know, ‘You’re somebody. You’re somebody. You can’t express it right now but you keep this in mind. You’re just as much as anybody, you keep it in mind.’ And then when the time for this came, we produced. And I think this has just been handed down.”

The modeling of behavioral courage by elders, in adversarial situations which is then exhibited in the actions of subsequent generations, we have termed “generational courage.” As a child I remember witnessing such courage in my mother, Dr. Jessie Bryant Mosley.

We had finished our shopping in a store located in downtown Vicksburg, Mississippi. Upon completion of payment, Mother wanted the item to be shipped to her in Edwards, Mississippi. The salesclerk asked my mother for her mailing address to which she responded by giving her name as Mrs. C. C. Mosley, Sr., and the mailing address.

How much younger than six years old I was, I do not remember, but since we still lived at Southern Christian Institute in Edwards, Mississippi, I know I was younger than six. It is my understanding that I began reading in first grade at the age of four; therefore, reading for me was not an issue.

As the salesclerk began to write my mother’s name, I noticed that she did not put “Mrs.” in front of her name, which of course I mentioned to my mother – children have no filters. “Mother, she did not put “Mrs.” in front of your name!” To which my mother responded, “That’s all-right Baby. When Daddy gets it, he will just send it back.” The salesclerk re-addressed the package.

I have never forgotten this incident and many other acts of courage modeled by my father and mother. Each of those teaching moments prepared me for the many difficult situations in life I would face as a black person.

During the month of March, for Women’s History Month, NMHS Unlimited Film Productions explored the concept of generational courage. Through the month-long series entitled The Legacy of Courage, which aired on The Women for Progress Network, the stories of five women, Gladys Noel Bates, Dr. Ollye Brown Shirley, Judge Patricia Wise, Oleta Garrett Fitzgerald, and Judge Constance Slaughter Harvey, were showcased. The panel discussion which followed each film included some of the women featured in the films, their daughters, and others. The subsequent results of this month-long discussion series are that indeed generational courage is the result of modeled behavior.

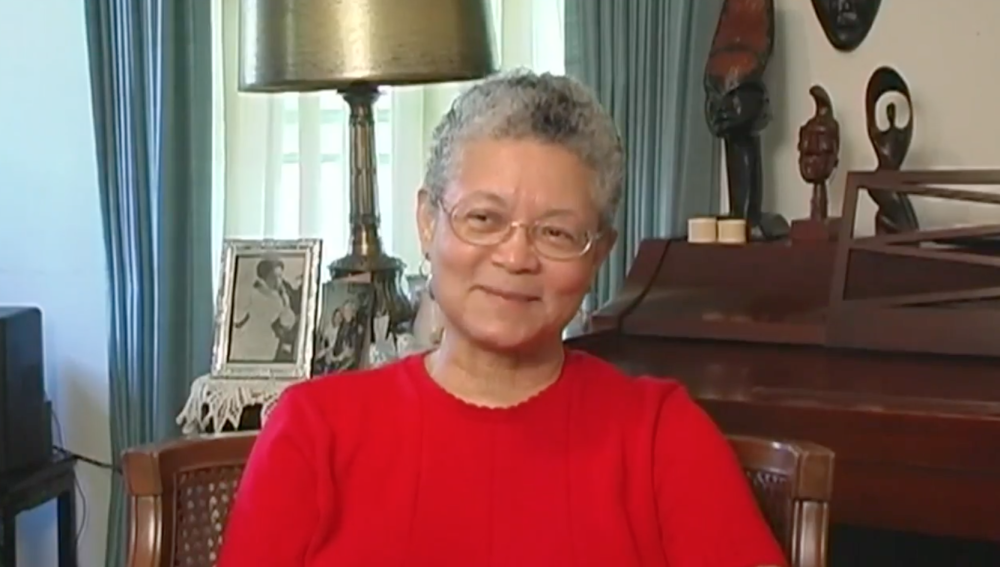

Let me take a moment to share with you excerpts from two works in progress which underscore this concept: (1) Conversations with Gladys and (2) I Remember My Father. Both films emphasize how Civil Rights traditions were passed on to the next generation by words and actions.

In the excerpt from Conversations with Gladys, Gladys Noel Bates mentions how her mother and father, both Civil Rights activists, shaped her life. Andrew J. Noel was a member of the Progressive Voters’ League and board member of the NAACP. In 1948, Gladys Noel Bates filed the first Civil Rights case in the state of Mississippi focused on equal pay for black and white teachers.

At this point I think it important to share with you Mrs. Bates’s remembrances of the conversation she had with her father about filing the case. Let me offer my apologies now for the quality of the audio. While conducting the interview, we were not able to locate a quieter setting. All efforts to clean up the sound were to no avail so we have added captions. The interview, which was conducted in March 2009, remains historically significant because it is the last video interview of her before her death on October 15th, 2010.

In her paper, Gladys Noel Bates: No Shrinking Vine (2003), Catherine M. Jannik gives us a glimpse into the lives of the Noel family beginning with Gladys’ grandfather James Noel, born in 1855. He was a slave on the Edmond F. Noel plantation in the Mississippi Delta. Following the end of the Civil War, James remained on the Noel plantation, in the same capacity, as a free person. When he reached adulthood, Edmond B. Noel, gave him seven acres of land.

Through the examples of their father and mother, the Bates children also understood that it was important to stand up for one’s rights

even in the most adverse situations...

It is on this land that James Noel began his family. As each of his sons reached adulthood, he gave them part of his land, a horse, and a buggy. Of his four sons, only Gladys’ father, Andrew, asked for money instead. He wanted to attend Alcorn College where he met and married Susie Hallie Davis.

The day after their marriage, the Noels signed a contract and set the tone for their marriage and for raising their children. In this contract the Noels stated that they would make every effort to educate their children, teach them to fear God and uphold moral standards. Later contracts were prepared for each of the Noel children in which they committed themselves to the same principles. The Noels were ambitious for their children, expecting each of them to become educated and enter a profession.

It is obvious from the interview with Mrs. Bates that all of them were taught how to survive. Through the examples of their father and mother, the Bates children also understood that it was important to stand up for one’s rights even in the most adverse situations; and that is exactly what Gladys Noel Bates did – even in high school. Let’s take a look.

Another example of generational courage is highlighted in our next clip which contains excerpts of a conversation with Karen Kirksey Zander, the daughter of renowned Civil Rights activist Senator Henry Kirksey. Using the demographic and mapmaking skills Kirksey honed while serving in the United States Army during World War II, he documented the racial gerrymandering of voting districts in Mississippi. This paved the way for the election of black officials then and now.

Senator Kirksey was unrelenting in filing lawsuits against county-wide legislative elections in 1965. His successful one-man battle to open the legislatively sealed records of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission led to the arrests and convictions in several unsolved Civil Rights era murder cases. Don Manning-Miller, in his article “Another Unsung Civil Rights Hero Dies,” characterizes Kirksey as a “...courageous and outspoken leader and activist in virtually every Civil Rights and political campaign in [Mississippi] following his return in 1962.”

In this segment of I Remember My Father, Zander discusses her relationship with her father. It was such an honor to be able to interview Senator Kirksey’s daughter. As a child, I remember my father and mother discussing the Senator’s endeavors quite often. Throughout this segment of the interview with Zander, you will see her father’s sense of humor shine through and his desire to represent those who could not fight for themselves reflected in her life’s ambitions.

In closing, I think it essential to understand how the definition of folklife within the construct of the Civil Rights movement is inextricably connected. Having seen many definitions, I settled on the one offered by the North Carolina Arts Council as a starting point:

For the enslaved African this folklife was a way to pass on the needed traditions and survival tools, based on traditional African customs, in order for each generation to survive.

Folklife is an essential and enduring part of how communities form their identity, learn from their pasts, and decide their futures. Folklife is a living and dynamic experience expressed through art, music, dance, celebration, work, story, dress, sense of place and belief. No community is without it, and we are all carriers.

In the New World, when the enslaved Africans understood that true survival required solidarity, it allowed them to see their common experience, and it is upon this commonality they began to build a folklife. For the enslaved African this folklife was a way to pass on the needed traditions and survival tools, based on traditional African customs, in order for each generation to survive. When the time came, their progeny were ready to step forward, and the modern Civil Rights movement was born.

Resources

Baptist, Edward E. The Half has never been Told. Basic Books, New York, 2014, p. xxvi, xxvii.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, U. of California Press, Berkley, 2007.

Links

Atkins, Joe. Henry Kirksey:1915-2005. Mississippi Encyclopedia, Center for Study of Southern Culture. http://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/henry-kirksey/, May 11, 2021.

Manning-Miller, Don. Henry J. Kirksey (1915-2005): Another unsung Civil Rights Hero Dies. Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement, www.crmvet.org/mem/kirksey.htm, January 1, 2006.