In an unassuming strip mall on the east end of Tupelo is a shop that serves as an oasis for one of Northeast Mississippi’s flourishing communities. There’s nothing quiet or demure about this space—the store announces itself boldly, its contents spilling out into the parking lot.

Above: Matt Robinson, owner of Change Skateboard Shop in Tupelo, stands in front of a wall of skateboards inside the store.

Left: A grind rail sits in front of an organ outside of Change Skateboard Shop.

Article Photography by Nicole Musgrave

To the right of the entrance sits a seven-foot long metal rail, standing about two feet off the ground. An organ decorated with painted skulls and bones and flowers is tucked behind the rail, and next to it is a large, handmade wooden sign. The sign is about five feet tall and six feet wide, covered in pink spray paint. In white lettering it reads, “Tyre Nichols Forever.” 1 To the left of the entrance is a two foot tall wooden platform with a metal rail attached to one side. Behind it stands another large wooden board, covered in brightly colored, bubbled graffiti lettering. The front door is peppered with stickers that boast names like Vans, Fallen, and Thrasher, along with statements such as “END RACISM” and “Keep Tupelo Rad.”

The outside of Change Skateboard Shop in Tupelo.

If it’s not totally obvious from all the cues on the outside, it becomes crystal clear when you walk through the door—this is a skateboard shop. The left-hand side of the store is packed with rows of helmets, shoulder and knee pads, hooded sweatshirts, flat-soled shoes, and polyurethane wheels. To the right sits an impressive indoor wooden skate bowl, surrounded by metal fencing. The walls in the back-right corner are a veritable art gallery, lined floor-to-ceiling with colorful skateboards that feature bold graphics.

Robinson put in an indoor bowl at Change Skateboard Shop. People from the community often come in and skate here.

The name of the place is Change Skateboard Shop, and its founder and owner is Tupelo native, Matt Robinson. I met up with Robinson on a sunny Spring morning in May to interview him for the Northeast Mississippi Hill Country Folklife Survey, a project of the Mississippi Arts Commission.

There’s no way to do it better than somebody else. Except for this kind of unquantifiable element called "style."

The Aesthetics Of Skateboarding

“Art” might not be the first thing that comes to mind for everyone when they think of skateboarding. To the outside observer, it's easy to corral skateboarding into the sports category. While skateboarding is definitely about physical skill, there are also elements of creativity and artistic expression that are inseparable from the practice. Robinson gave me a crash course in the aesthetics of skateboarding. He explained that in part, it has to do with a skateboarder’s style.

“There’s no way to do it better than somebody else. Except for this kind of unquantifiable element called ‘style,” Robinson said. “They just look cool, right? They just look like they're effortlessly doing this thing that they could—at any moment—have an arm torn off their body or whatever. And they just don't care. So it's unquantifiable what style is, but you know it when you see it.”

While visiting Robinson, he explained to me that skateboarding has an improvisational quality to it. Like dance or jazz, skateboarding is an outlet for individual expression. It’s less about the repertoire of technical moves you can execute, and more about how you look when you’re doing, say, a kickflip or frontside air.

“You can't score more goals than the other team. And yet, we're in the Olympics now, right? And there are contests,” Robinson said. “And I think it's just one of those things where you have to—you almost have to look at it like it's martial arts and dance, and gymnastics on a skateboard. I mean, it takes an incredible amount of physical strength and training and commitment. And you can recognize that and celebrate that. But in the end, do you look good doing it or not?”

What constitutes style in skateboarding goes deeper still. “It’s your whole aesthetic that you're putting out there. It's fashion, it's the kind of art that's on your board. It's what you do to your grip tape, right? I mean, most people, they're putting their grip tape on top of the board and they take paint pens and put stuff on top of it, or write their name on it, or whatever. There's a lot of graffiti,” Robinson said. “So the way that it looks is inseparable from the actual doing of the thing.”

Several skateboards that have been decorated with graffiti art.

The bathroom at Change Skateboard Shop is adorned with graffiti art.

Skateboarders also embody the spirit of improvisational creativity in the way they play off of their physical surroundings. “You have skateboarders who are interacting with their environment. Like where you live, there may be a lot of parking blocks. Where another person lives, there may be a lot of empty swimming pools. You know, where somebody else lives, there may be parking garages or a lot of really great granite ledges and marble ledges in your downtown,” Robinson said. “So skateboarders are interacting with their environment. And each individual is going to interact with that environment in a different way.”

DIY Or Die

The way that Robinson has interacted with his environment says a lot. It’s not a stretch to claim that he is Tupelo’s biggest champion of skateboarding. Robinson—who’s in his 40s—first got into skateboarding when he was ten years old. Not long after, he stumbled upon the skateboard magazine Thrasher, where he discovered there was a whole culture surrounding skateboarding—a culture that included music, graffiti, fashion, and art. Eventually, he convinced his aunt to take him to the nearest skateboard shop in Memphis, Tennessee, called Cheapskates. "That was the first place that I actually touched this culture that I'd seen in the magazines,” Robinson said. "I knew, like, this is the coolest place in the world. And this is what I want. This is what I want to be.”

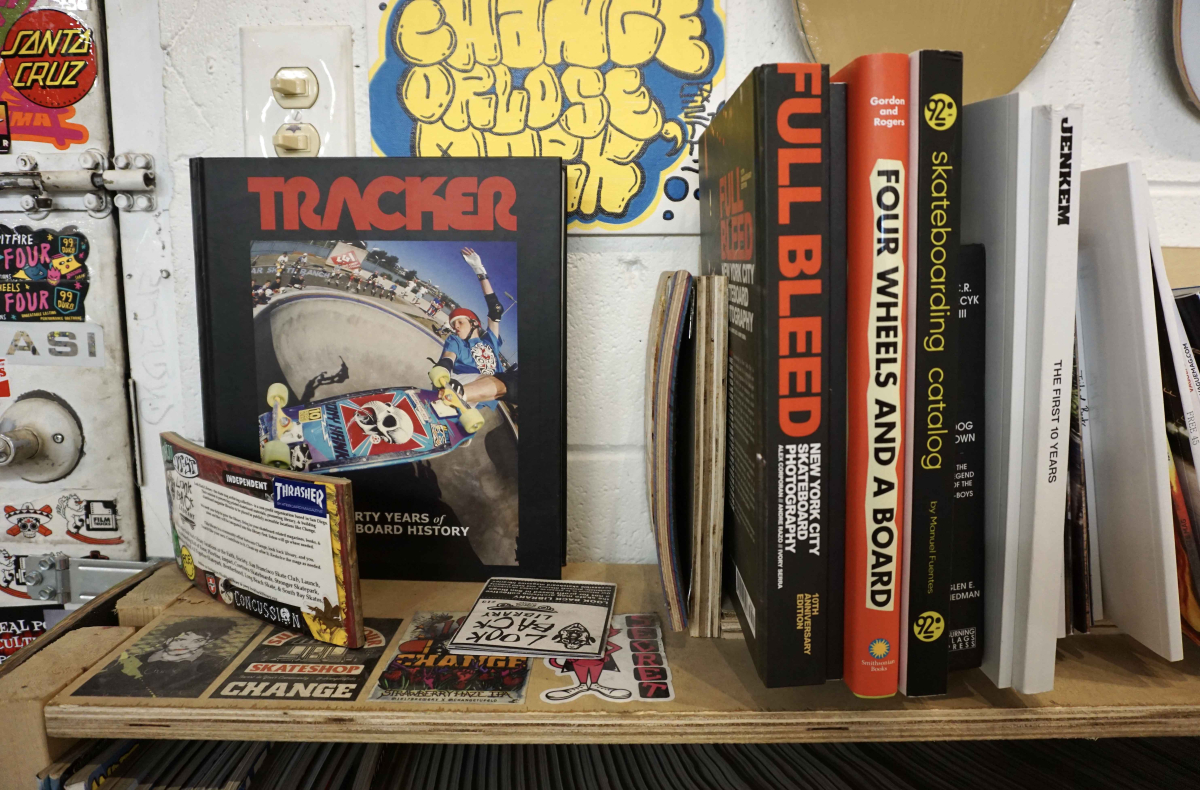

Robinson has a bookshelf at Change Skateboard Shop that features a variety of books and magazines about skateboarding. It serves as an archive for the community.

After graduating high school, Robinson opened his own skateboard shop in Tupelo called Sideshow Skateshop. It drew people in from all over northeast Mississippi. “They would be from Corinth, down to Columbus, over to Oxford, and Batesville, over the line into Alabama,” Robinson said. “This was just where people started coming on the weekends because they heard there was a skate shop. And that led to friendships, and that led to giant bands of skateboarders in the streets.”

As the skateboarding community around Tupelo grew, so did the need for safe places to skate. “Tupelo is a tiny island of concrete in a sea of pine trees and pastures,” Robinson says. “And so there's not a lot of concrete. And so the little bit that we did have was contested ground between us and the property owners.” Needing a sanctuary from the tensions that were forming between the skate community and police and businesses, Robinson rented out a warehouse and built the first indoor skatepark in the area, with DIY plywood ramps and hand poured concrete structures.

Eventually, Robinson started hosting local and national touring punk rock and hip hop acts at the warehouse space. It was a way for him to introduce younger people to the culture of skateboarding. "I don't know if I realized at the time, like, ‘Oh, this is helping shape a DIY, punk rock and art and music culture in the area.’ But I just knew that it was turning people on to things I'd been turned on to through skateboarding.”

Robinson stands inside the bathroom of Change, looking at an enlarged photo by artist Glen E Friedman. The photo is of people dancing at a show by DIY punk legends Minor Threat in New York City in December 1982.

One thing it was turning people onto was the DIY ethic of skateboarding. Through his scrappy initiative, Robinson demonstrated to others in Northeast Mississippi’s skate community the importance of self-sufficiency and a figure-it-out-as-you-go attitude.

Part of my work is working with people in the communities all around Mississippi to try to build public skate parks. Still, it's DIY or die.

“Nobody's going to build you a skate spot in your little town. If you go and tell your little town we need a skate park, they're gonna say, ‘Dude, we need traffic lights. We need to fix our potholes, and we need a lot of things,’” Robinson said. “Part of my work is working with people in the communities all around Mississippi to try to build public skate parks. Still, it's DIY or die. And so, we learn how to pour concrete pretty early on. Like, that's part of the culture. We have little secret DIY spots around town where—if a place burns down and there's a slab and nobody's using it? Well, we'll use it. You know, it's flat concrete, it's out of the way, nobody's really paying attention. And so the kids learn, instead of sitting around complaining that there's nothing to do, you got to go out and do it yourself and make something.”

Building The Next Generation Of Skaters

While Robinson exalts the importance of the DIY ethic of skateboarding and works to pass that on to young people in the community, he’s also found ways to work within more formal channels. He helped found the Tupelo Skate Board, a nonprofit under the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation that builds public skateparks around Tupelo. He has partnered with the Tupelo Convention & Visitors Bureau to put on the Change Festival, an annual Labor Day Weekend event that showcases the art and culture of skateboarding. Robinson has also done work in the community under the Change Tupelo Foundation, a special project of CREATE, which exists to create and maintain healthy and sustainable communities by providing and promoting the benefits of skateboarding and the arts to Northeast Mississippi.

The skate bowl at Change.

One of the benefits of skateboarding that Robinson spotlights is how inclusive the community around Tupelo is, how the practice draws in people of various gender and ethnic and racial identities. But he explained that within skateboarding’s history, this hasn’t always been the case. “Skateboarding was kind of this California white boy thing to do back in the 70s and 80s. Somewhere in the 90s, it started shifting out of the parks and more into the streets,” Robinson said. “Today, it's like the most effortlessly multicultural thing. I mean, nobody has to be like, ‘Let's start a multicultural initiative in the skate park.’ You just go out there and it's everybody.”

Skateboards line the wall near the steps that lead to the bowl.

After many years of planting seeds, the skate scene in Tupelo is flourishing. Through his current work at Change Skateboard Shop, Robinson tends to the continued growth of the scene. Robinson opened Change in 2020. It’s the most recent iteration in the long line of skateboard shops he’s owned and operated around Tupelo—places like Sideshow, TCBSK8SHOP, and Lifeblood. In addition to serving as a mentor himself, Robinson also encourages many of the community’s seasoned skaters to initiate the newbies into the culture. "It's just ingrained into the culture—this whole 'each one, teach one' thing. And to always be investing in the youth,” Robinson said. “Because if you don't do that then the scene goes away. The culture stops growing.”

Footnotes

- ^ Tyre Nichols, a Black man, was murdered by police in Memphis, TN in January 2023 at the age of 29. He is remembered as a passionate skateboarder, learning to ride in his hometown of Sacramento, California. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/29/1152387262/remembering-tyre-nichols