My folks can tell the tales of the blues the classics...and no matter the situation – somewhere, somebody was always singing about a maintenance man, a clean-up woman, and old low-down Jody Ryder.

When I was younger, I spent every weekend in my mother’s hometown of Utica, Mississippi, a small, rural community located just south of Vicksburg. We drove thirty-two miles up Highway 18 until we reached the Spanish moss trees that masked dirt roads, shotgun houses, and the old-country-store-by-day turned hole-in-the-wall-juke-joint-by-night. Then we headed to Aunt Maxine’s house, where all the magic began.

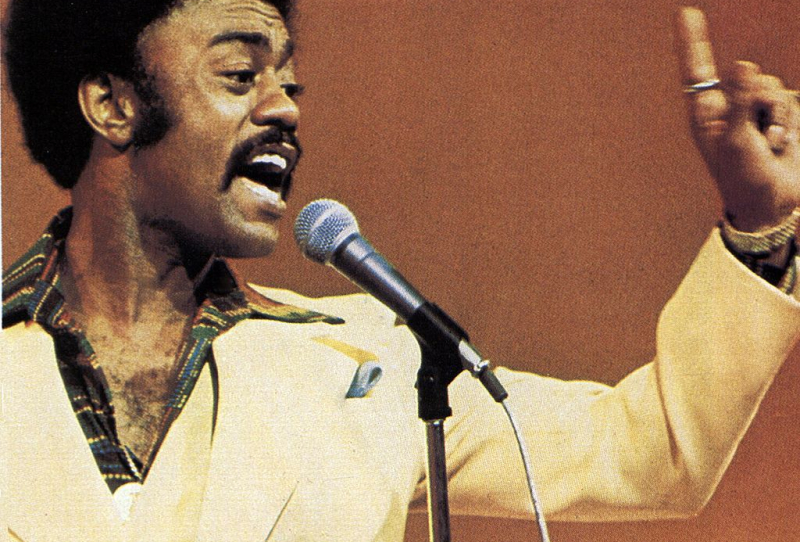

When we arrived, Aunt Maxine and my other aunts, uncles, and cousins would be sitting in the shade under an old Mimosa tree, eating pigfeet and neck bones flavored with onions, garlic, and hot peppers, drinking whiskey, cussin’, laughing loud, and listening to the soul blues. My folks can tell the tales of the blues: the classics were always Johnnie Taylor, Betty Wright, Mel Waiters, Marvin Sease, and T.K. Soul. And no matter the situation – somewhere, somebody was always singing about a maintenance man, a clean-up woman, and old low-down Jody Ryder. While I did not always understand ‘exactly’ what the bluesmen and women were talking about, I knew three things: that the maintenance man would fix your woman, the clean-up woman would take all the love another woman left behind, and Jody would get your girl and be gone! I watched as the grown folks would swing out, their silhouettes illuminated by sweat and lightning bugs, grooving and juking with the fictional characters of the soul blues, until night fell.

Together, all of those characters introduced me to the soul blues – an experience, a feeling, the culture of a place.

Chapters:

Jody's Got Your Girl and Gone

Jody is perhaps the most mysterious and influential figure within the southern soul-blues genre. He often creeps into black men’s homes while they’re hard at work and does “who knows what” with and to their wives. Jody is the contemporary of “Joe De Grinder,” a black man who would steal the wives of black soldiers and prisoners during WWII. Bruce Jackson writes that Alan Lomax recorded a man named Irvin “Gar Mouth” Lowery signing Joe de Grinder in 1939. The man in the song is bellowing out:

He call me Joe de Grindarrrrr

oh baby, I’m going home

Folklore suggests that it was African American soldiers who introduced the Jody chant into the U.S. Army. In one military running cadence simply titled, Jody, men are heard in the background chanting:

Ain’t no sense in going home (x2)

Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone (x2)

Ain’t no sense in feeling blue (x2)

Jody’s got your sister too

Although Jody’s origins are obscure, he remains a dominant figure in contemporary blues mythology.

Johnnie Taylor’s 1970 hit, Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone, is one of the earliest soul-blues representations of Jody, and Taylor depicts Jody as a complex and ambiguous figure. Taylor opens the song with:

Every guy I know / trying to get ahead / working two jobs till you’re almost dead (you tell ‘em!) / work your fingers / right down to the bone / there’s a cat named Jody / sneaking around in your home.

This image of a black man working hard to provide for his family reflects black men’s frustrations with hard labor and the realities of black working-class life, and it suggests then men are anxious and suspicious about what goes on their homes while they’re off providing for their families.

If a man such as Jody is skilled enough to sneak into a man’s home and steal his woman and everything he’s worked so hard for, then what is the point in working so hard in the first place?

Jody appears, in some instances, as a Southern human-fusion of black and white masculinity.

In the next verse, Taylor sings:

There’s a cat named Jody / in every town / spending lots of cash / and just riding around.

This verse functions in two ways: first, it serves as a warning to black men about “Jody’s type,” and second, the image of Jody spending lots of money and “just riding around” suggests that a man with enough money to “just ride around” apparently has the means to get what he wants, when he wants, and how he wants it, including other men’s women. Jody’s agency is clearly demonstrated in Taylor’s next verse:

Jody leave ashes / in your ashtray / footprints on your carpet / while you work all day / he even got the nerve / to sleep in your bed / sit down at the table / eat your bread.

Taylor continues:

When you get home / after working hard all day / Jody’s got your girl / and he’s gone away.

Jody’s entrance into and authority over any man’s house is emblematic of his ability to wrest agency from other men. Jody’s ability to come into a home and to take control over the masculine spaces – the ashtray, the bed, and the head of the dinner table – demonstrates his fearless, assured, and intimidating nature.

Jody’s ability to come into a home and to take control over the masculine spaces – the ashtray, the bed, and the head of the dinner table – demonstrates his fearless, assured, and intimidating nature.

What adds to Jody’s ambiguity is that he is never explicitly racially identified in soul-blues song lyrics. Audiences assume that Jody is black because he appears in the lyrics of songs sung by African American musicians. However, it is important to examine Jody exactly as he appears in the narratives. If Jody is read as “unraced,” then the ways that he functions in the narratives suggest that he represents a conflation of both white and black southern masculinities; that is, Jody is a black man who possesses the power typical of Southern white males: he can disrupt the lives of black men, possess their women, and take authority over their homes according to his own free will. The idea that these types of men may be lurking among us, in our communities, and are of our same race makes Jody that much more of a threat to black men.

The ironies within these soul-blues narratives emerge when men realize that if only they took care of their women "right," in the first place, Jody would have no reason to come in their homes to pick up their slack. In one of Taylor’s final verses, he sings:

When you discover / your gross neglect / it’ll be too late / to give your woman respect / you’ll hunt down Jody / dead or alive / ten thousand dollar reward / for Jody’s hide.

Taylor’s message is that while men have to work hard and long to provide for their families, hard work does not exempt them from “providing” for their wives romantically. In this vein, Jody serves the interests of women, and as we will see later, Jody works wonders as a rhetorical figure.

I'm Mr. Jody, I'm Doing My Job

Jody works in conjunction with black female agency in strategic ways, and black women often use their husband’s money to support Jody financially, and in return for his sexual favors.

Marvin Sease’s 1994, I’m Mr. Jody, is the most pertinent example of this relationship. In this song, Sease takes on the persona of Jody, and he reveals how Jody comes by his material things. The song begins with Sease narrating a call between himself and another man:

A man called me

And said, “Mr., Please let me speak to my wife.”

Sease / ”Mr. Jody” asks the man who he is, and the man responds:

You mean to tell me

You don’t know my name

After all I’ve done for you?

After Sease questions the man about his identity once more, the man replies:

…well / I’m the man / who bought that car you’re riding in / and um, I’m the same man / who bought all those clothes / that you wear.

The man continues:

…I know / you must think I’m a fool / but if that’s what it takes / to keep the little fine thang / …I don’t mind / I sho’ don’t mind.

Mr., I don’t mind / being your fool / but tell me one thing, Mr. / what is it you got that I don’t have?

And what do you do, / that I don’t do? / that make her stay out all night long? / all night long from me?

At this point Mr. Jody freezes and contemplates his reply. “Before [he] knew it…these words came to [his] mind”: He said:

It ain’t / what you got / it’s how you use it / it ain’t / what you do / it’s how you do it.

I said, if you can’t keep / your woman from me / it’s your fault, man leave me alone.

I told him leave me alone / I'm Mr. Jody (Jody, Jody) / I’m doing my job.

The wife of the man who called and interrogated Mr. Jody had been giving her husband’s money to Mr. Jody in return for sexual intercourse. To say, “it ain’t what you got, it’s how you use it,” or, “it ain’t what you do, it’s how you do it,” signifies a physical extraordinariness on the part of Jody. Regardless of how much money he has, he is never insufficient when it comes to sexual performance.

You Better Call Jody

While many male soul-blues singers view Jody as a threat, some of them use Jody as a rhetorical strategy to convince their women of their worth. Sir Charles Jones’ 1998 Better Call Jody begins with a dedication by the male narrator to “all the cheaters out there,” especially his former lover.

This song is for you

And ol' dirty Jody.

To the lady who did him wrong, Jones sings:

When you get hungry / You better call Jody.

When the bills get high / You better call Jody.

When you get sick, no insurance / You better call Jody.

‘Cuz I’ll be long, long gone / You better call Jody.

It is important to understand this song’s multiple layers. Jody is the cause of this man’s failed relationship, but instead of lamenting the relationship’s ending, the narrator uses Jody as a counterattack on his former lover. In other words, “although you left me for Jody, Jody won’t be able to take care of you like I can.” The narrator is also subtly telling his former that if Jody takes care of her sexually, he should be the one to take care of her financially and emotionally as well.

Looking for My Baby

Jody is often depicted as a trickster-figure in many soul-blues narratives, and he usually has access to other men’s women because he is, unbeknownst to the men, one of their close friends. T.K. Soul’s 2003 Where Jody Stay captures this relationship perfectly.

T.K. Soul begins by explaining that his wife had been having dealings with Jody, so he went looking for her all over town. He sings:

Can you tell me xxx? Jody stay?

I’m looking for my baby

Can you tell me where Jody live?

I’m looking for my wife.

He gets to a house, knocks on the door, and a man lets him in. To the man, T.K. Soul says:

You been my best friend

For going on twenty years

But I been all over town and they all say,

‘This is where Jody live.'

The man responds:

Man I don’t know what to tell ya

but you got me all wrong

She’ll show up sooner or later

You just need to gone on home.

T.K. Soul continues:

As I felt like a fool, y’all

And started to apologize

She walked out of the bedroom

Wearin’ nothin’ but a smile…

Jody was about to fool his friend into thinking that his woman was not there with him, but in a twist of fate, the woman walks out of the bedroom. What is remarkable about this narrative is that the narrator’s wife, like the wife in Sease’s I’m Mr. Jody, is complicit in the affair; both she and Jody are tricksters. This scenario reinforces the earlier notion that black men are, and in some cases have every right to be, suspicious about their women’s goings-on.

The Allusion of Jody

Jody also transforms into other figures, and like many soul, R&B, and rap artists, soul-blues singers create female versions of Jody to warn women of the potential of other women coming into their homes and stealing their men. T.K. Soul’s 2004 Jodette is the most pertinent example of this. He notes that Jodette “can’t be beat” when it comes to the love game; for this image to work as an allusion, it reinforces Jody’s omnipotence and universality.

An earlier variation of Jody is presented in Charles Wilson’s 1995 Old Man Jody’s Son. At the start of the song, Wilson introduces his audience to “a brand new fella” who is in “every town” “sneakin’ ‘round the block” and “workin’ ‘round the clock.” Because, according to Wilson, Jody had gotten too old, a cat named Jody Jr. has emerged to fill his daddy’s role.

Labor, for Southern black men, is both a means to an end and a heavy burden to bear, and Jody reflects this reality by appearing, in some instances, as a Southern human-fusion of black and white masculinity, in others as a pimp, but always as a manifestation of southern black male anxiety around status, power, control, women and work. To tell Jody to “Ride On,” as Johnnie Taylor does, is to both endorse and dismiss his status and power.