Robert Kimbrough Sr. sold me a shirt on the day that I met him at the 2015 Juke Joint Festival in Clarksdale, Mississippi. The shirt was a pale-yellow and it had an image of Robert with his late father, the blues legend Junior Kimbrough, hovering above him, floating in the clouds alongside an assortment of other passed blues icons. Robert wore the shirt during his band’s set outside the Cathead Delta Blues and Folk-Art store that afternoon. It was printed in support of the release of Robert’s new single, “Packin’ up,” the lyrics of which were inscribed below the image. “Packin’ up” is an easy groove built on a direct quotation of one of Junior’s most well-known songs, “Meet Me in the City.” As he picked the familiar opening notes of the guitar riff, Robert explained that he had been inspired to write the song upon being visited in a dream by his father. As the rest of the band settled into the relaxed shuffle, Robert delivered the central message of the lyrics, that he was “packin’ up, getting ready to go up the city where daddy and them went.” In the original song, Junior calls on a lover to meet him in the city. Robert’s city is a more complex space, his trip remapped onto the specter of death and the promise of heaven. The song is built around a memory he shares of Junior telling him that he would someday pass away and be ‘packin’ up,’ headed to the city.

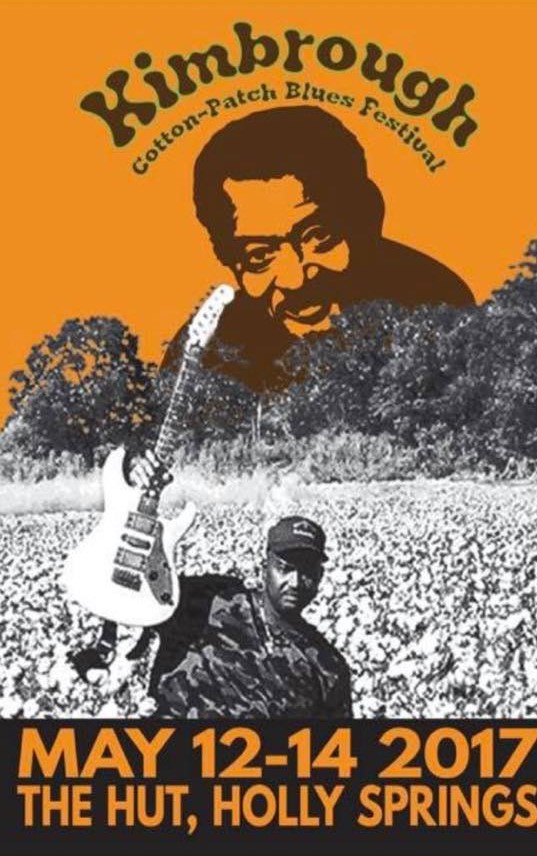

This song, like the shirts the Kimbroughs sold, is a lament for Junior Kimbrough, a personal negotiation of death and movement through time and space juxtaposed with the simple melodic saunter of one of Junior’s most beloved songs. The rest of Robert’s set that day was rife with direct and personal remembrances; the new album he was set to release, “Wiley Woot,” is almost fully devoted lyrically and sonically to grieving and remembering his late father. Robert’s music is different from Junior’s in a lot of important ways. It’s a more contemporary sound that definitively communicates the stylistic characteristics of what the Kimbrough family calls ‘cotton patch soul blues,’ a personalized subgenre that Junior claimed, and that Robert has taken on as a torch to bear. Across social media and other arenas of musical discourse, Robert is constantly standing up for his father’s claim that the Kimbrough sound is not adequately classified as Hill Country blues, and that those scholars and experts that would claim otherwise mischaracterize his family. Beginning in 2017, Robert inaugurated an annual blues festival in Holly Springs, Mississippi called the Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival. Held at a local VFW hall commonly known as ‘the Hut,’ the Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival is a multi-day event that is committed to carrying on family traditions, keeping the memories of Junior’s clubs and parties alive and educating fans about the cotton patch soul blues sound.

Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint is the stuff of legend in North Mississippi. Memories of partying at Junior’s carry a cultural currency that stretches across the region and across the international community of blues fans that celebrate his music. These memories have circulated in tall tales told first by local Holly Springs residents and the occasional Ole Miss frat boy, and later by music critics and the blues tourists, who by the 1990s had begun seeking out Junior’s regular Sunday night parties. The vibe of Junior’s all-night trance-like grooves was captured in the clip of his classic song “All Night Long” in Robert Palmer and Robert Mugge’s 1992 film “Deep Blues.” In that clip, filmed in 1990 at Sammy Grier’s Chewalla Rib Shack in Chulahoma, Mississippi, Junior is joined by Earl “Little Joe” Ayers on bass and Calvin Jackson, son of R.L. Burnside and father of Cedric Burnside, on drums. A couple years later Junior would release his debut full length album, “All Night Long,” on Fat Possum Records, accompanied by his son Kenny Kimbrough on drums and another of R.L.’s sons, Gary Burnside on bass. Junior’s Fat Possum releases earned him international recognition as one of the most exciting blues voices of the era. His juke joint became a destination for the growing numbers of blues fans making pilgrimages to North Mississippi as the turn of the century grew nearer and blues tourism began to take hold in the state. After his death in 1998, Junior’s sons continued to host parties under the auspices of Junior’s Place, until it burnt to the ground in the spring of 2000.

Kimbrough Brother's Band playing on Friday night at the Hut. Photo by Ben DuPriest.

Marquee sign outside the festival. A similar sign sat outside Junior's club, as seen in the iconic clip featuring junior in the film “Deep Blues.” Photo by Ben DuPriest.

Robert is Junior’s youngest son. His brothers David and Kenney had much more of a public musical presence at Junior’s place while their father was still around, performing with him and developing their own projects as prominent members of a younger generation of blues musicians based out of the North Mississippi Hill Country. Robert came to a professional career in music later in life, and quickly took up the responsibility of upholding his father’s legacy. He began the Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival in 2017 for this explicit reason. “The whole point of this festival,” he told me in a 2018 interview, “is to honor my father. I wanted to have a party he would have and make sure people recognize his music for what it is.” Organized and funded through work done by a group called ‘The Son and Friends of Junior Kimbrough,’ the festival spans three days and has maintained the same general schedule it used in the inaugural 2017 event. The weekend begins with a photo exhibit held at Rust College, a historically black college in Holly Springs, and continues with a series of open jam sessions, a guitar workshop, a guided historical tour, a ‘juke joint night’ featuring Robert and his brothers performing as the Kimbrough Brothers, and a proper day-long outdoor festival stage with artists representing a range of regional styles from Delta blues to Hill Country blues and beyond. Throughout the weekend a giant grill continuously burns, and local family and friends of the Kimbrough’s mingle with a crowd of regional, national, and international tourists and fans of cotton patch soul blues and Hill Country music.

The Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival is a multi-day event that is committed to carrying on family traditions, keeping the memories of Junior’s clubs and parties alive and educating fans about the cotton patch soul blues sound.

Festival Flier. Courtesy of The Son and Friends of Junior Kimbrough.

The festival is meant to be a long form recreation of the all-night jam sessions at Junior’s Place and the yard parties that Robert remembers from his childhood. While the basic notion of carrying on tradition is fundamental to this exercise, Robert’s motivations run deeper, into a defense of his own memories against the prevailing narratives surrounding his father’s music. He laid out the specifics of what he wants to communicate in a conversation we had about the festival: “see, my dad has been misrepresented… he never was a Hill Country blues player. They did interview him, and he did explain to them that he didn’t play that kind of music… He told them ‘I play cotton patch soul blues…’ But still everything has that he’s a Hill Country blues player... By them doing that, my daddy’s not being recognized right… So that’s what we’re working on trying to clean up.” Much of Robert’s time is spent combating what he sees as a historiographical misrepresentation of the Kimbrough sound. He is constantly debating with fans and experts on social media who identify Junior as a Hill Country blues musician. Many writers and critics have argued that Junior Kimbrough’s music was foundational to the codification of the Hill Country blues as it has been popularly conceived. To listen to many of his songs is to hear some of the best examples of those characteristics that have been used to describe Hill Country blues; the drone, the groove, the simple chord structures, etc. But in interviews that Robert has shared, including one with Jas Obrecht and Peter Lee, Junior specifies that he played cotton patch soul blues, and explicitly states that he was not a Hill Country blues musician. Robert’s own memories mirror this, he recalls his father describing his music to him as cotton patch soul blues, and never employing the Hill Country moniker. The cotton patch soul blues sound as described by Robert relies heavily on its relation to other genres, particularly soul blues, gospel, funk and rock. This is primarily born out in the rhythms, which do not borrow on the fife and drum traditions to which Hill Country blues is often connected. That these associations situate the Kimbrough’s music more within the realm of popular music rather than folk tradition is not lost on Robert and his music. Listeners are at least as likely to hear a cover of “Purple Rain” at a Robert Kimbrough concert as they are to hear the standards of the Hill Country tradition.

In Mississippi’s blues tourism industry, personal memories and emotions are absorbed into a larger project of public history, engendering the collective memory of America’s musical roots and enriching the affective experience of blues fandom for festival attendees.

Plenty of musicological scholarship has shown how genre labels and stylistic boundaries are mapped onto musical categories ex-post facto by cultural brokers, frequently fitting the needs of discourse or marketing strategies as much as they do the form, function and social life of the musics they describe. Robert’s argument bears this out in the contemporary moment. Conversations we’ve had are effectively a practice in generic deconstruction; he explains to anyone that will listen that people came in after the fact and named the music what they did, more or less ignoring his father’s own words and the memories that he and his brothers treasure. It is these memories that form the basis for the festival. Robert’s musical dedication to and remembrance of his father is quite personal, but in performance and on public platforms, they are absorbed into a larger process of collective memory that forms the basis for the community of fans and families that is so valuable to this musical culture.

The festival, like so many of Robert’s songs, is about reconstructing and communicating memories.

Theories of collective memory, the presence of the past whereby a collective defines itself, help us to better understand the relationship of influence that exists between the community and the individual vis-à-vis historical consciousness. The collective is essentially a theory of agency in memory governance. Robert reconstructs his own past through musical memory as a means of communicating with listeners and fans. As visitors re-inhabit the affective experience of Junior’s Place, the Kimbrough family’s remembrance of the club is set in the context of cotton patch soul blues and family memories are able to prevail over popular and conventional narratives. This process of memory tending is one basis for the production of public historical consciousness; memories are mediated through collective experiences. At festivals where strangers celebrate in the personal remembrances of strangers, local knowledge is privileged.

Earl "Little Joe" Ayers, an original member of Junior Kimbrough's band, teaches a workshop class. Photo by Ben DuPriest.

This is why the festival workshop, a collective masterclass on cotton patch soul blues musical style and technique, is particularly dear to Robert. Beginning early Saturday morning of the festival weekend, Robert, his brothers, and Little Joe Ayers, an original member of Junior Kimbrough’s Cotton Patch Soul Blues boys, teach guitar and drum lessons. Fans who pay the VIP admission to the festival bring their guitars and amps and sit for masterclasses with these musicians, learning and discussing the specifics of the cotton patch soul blues sound, sometimes in relation to Hill Country and Delta blues styles. The cathartic product of this process comes later that night, when the Hut is transformed into a simulacrum of Junior’s club. A jam session takes place during which the Kimbrough Brothers hold court and various ‘students’ of the workshop sit in intermittently as long form versions of Junior’s hits are played. In this reconstruction of Junior’s juke joint, Robert and his brothers’ memories and nostalgia for the club are performed and experienced by all who attend.

Robert Kimbrough teaches a workshop class on cotton patch soul blues guitar style. Photo by Ben DuPriest.

In the most basic sense, these events and practices reflect the simple fact that these are living breathing communities, and their traditions and musics are no more of the past than the musicians themselves are, no matter how many of them head to the city.

One of the songs that Robert frequently includes in his regular sets is called “View the Remains”; in it he works through the grief he experienced when his father’s club burned down. The song is an interesting example of the frictions and slippages present in his project. To be sure, going by conventional theories, “View the Remains” is not a Hill Country blues song. There are multiple chord changes, a four-on-the-floor drum loop and background synth-pad harmonies. Nor does it bear much resemblance to Junior’s music. It is, however, an excellent example of Robert Kimbrough’s cotton patch soul blues. It represents his understanding of how the music and the traditions have lived on into the current moment. The festival, like so many of Robert’s songs, is about reconstructing and communicating memories. The rebuilding of past experiences creates a contemporary moment in which Robert can contest the histories that he takes issue with, rehearsing and performing the meanings and values that he holds dear in a performative memorial space that is easily situated within the heritage celebration of the festival context. In Mississippi’s blues tourism industry, personal memories and emotions are absorbed into a larger project of public history, engendering the collective memory of America’s musical roots and enriching the affective experience of blues fandom for festival attendees. The Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival is a way of carrying on and honoring tradition and tending to the perception of Junior Kimbrough’s music at the level of public memory. Robert is carrying on the traditions that he knows his father believed in: cotton patch soul blues and juke joint parties. These events may not resemble the material realities that Junior lived and performed through, but how could they, two decades after his death? Carrying on these traditions demands collective memorial practice, but living them in the contemporary moment forecloses on their precise resemblance to the past. In the most basic sense, these events and practices reflect the simple fact that these are living breathing communities, and their traditions and music are no more of the past than the musicians themselves are, no matter how many of them head to the city.