Croom’s photographs encourage the viewer to become familiar with the Rowan Oak landscape and the plants that inhabit it, but at the heart of The Land of Rowan Oak is William Faulkner himself.

In 1930, just after marrying his wife Estelle, William Faulkner purchased the land and home that would become his beloved estate, Rowan Oak. Located in Oxford, Mississippi, where Faulkner’s family moved only a few years after his birth in 1897, the two story home was built in 1844 by an Irish planter from Memphis named Colonel Robert Sheegog. The home sits on 4 acres of manicured grounds that had fallen to ruin, and another 29 acres of un-manicured land, known to locals as Bailey Woods, after the property’s second owner Ms. Ellen Bailey who gave china painting lessons in the library. Many years had passed between owners before Faulkner purchased the home and property, and the house and grounds had fallen to disrepair. After several renovations, Faulkner almost doubled the floor plan of the home, added plumbing and electricity, and brought the grounds back to life while maintaining their romantically ruined state.

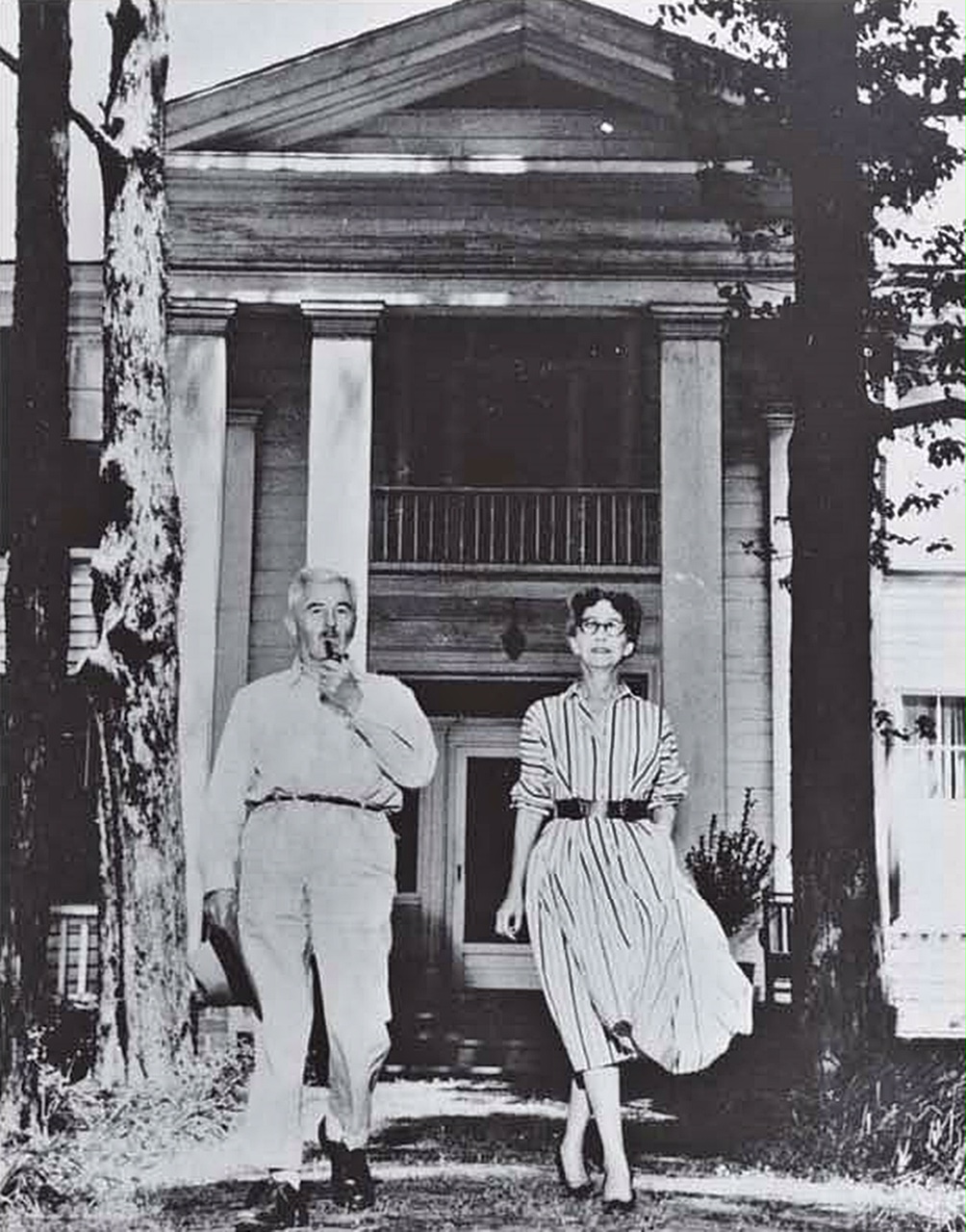

William and Estelle Faulkner in front of Rowan Oak featured in The Land of Rowan Oak. In 1955, after Faulkner won the Pulitzer for A Fable, he and Estelle posed in front of their home for this shot by UPI photographers (Cofield 164).

Photograph courtesy of the Louis Daniel Brodsky Collection of William Faulkner Materials, Special Collections and Archives, Southeast Missouri State University.Faulkner, who wasn’t always the most social man, established a reputation as a reclusive writer, and, possibly to be contrary, named the property after two trees that do not exist on the grounds. Rather, he named the property after the spirit of the trees. The Rowan tree is native to the United Kingdom and mythologically protects against evil spirits, like reporters and tax collectors, and the Live Oak symbolizes strength and solitude. Faulkner cared for Rowan Oak, both the home and the grounds, which include a stable, barn, detached kitchen which the family used as a smokehouse since the Bailey’s added a kitchen to the home, and servant’s quarters. Faulkner used the grounds for hunting, and often worked outside, with his typewriter perched on a small portable desk while he sat on an adirondack chair.

When we compare [Rowan Oak] to the rest of Oxford, I think it’s a kind of nature reserve, and historic landscape. All that, right here, there’s no other place like it.

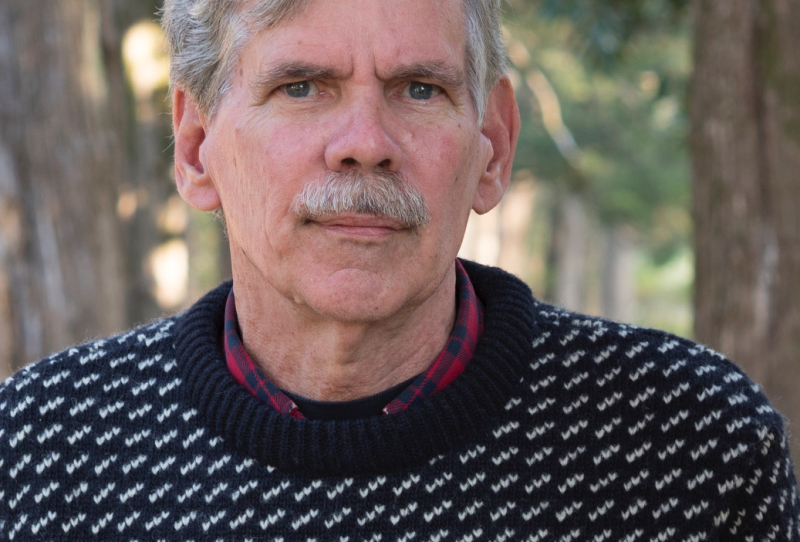

Today, the house and grounds are owned by the University of Mississippi, and operate as a historic museum. Thousands of visitors come to Rowan Oak to learn more about the Nobel Prize for Literature recipient, and even more hike the trail through Bailey Woods, or walk around the gardens where the scent of gardenia saturates the air through the summer months. One of these visitors is Ed Croom, a resident of Oxford since 1982 who is often the first visitor to Rowan Oak every day, carrying his tripod and photographing the grounds and surrounding woods in the early morning. The Land of Rowan Oak, published in 2016 by the University of Mississippi Press, is a collection of 147 original photographs, mostly in color, taken by Croom over more than ten years.

While Ed Croom found Rowan Oak to be a quiet sanctuary for him to spend time alone in nature, he noticed it was a similar place of refuge for others.

Croom has had a longtime interest in plants. He started working in ethno-botany in North and South Carolina around 1976 as a graduate student. Croom was particularly interested in documenting indigenous people’s relationship to plants through photography. When he left the Carolinas to become a full-time research professor in the School of Pharmacy at the University of Mississippi in 1982, he re-established its medicinal plant garden. Through his work, Croom dedicated himself not only to the research of medicinal plants, but the preservation of the knowledge of folk medicine practitioners as well as conservation of plants and nature.

Another important aspect of Croom’s work, and something he feels very strongly about, is documenting people’s relationships to plants, which was also one of the main goals of his book. He started taking the photographs at Rowan Oak out of a personal desire for peace and quiet:

When I started this, I moved to Oxford in 1982. I always thought Rowan Oak was just a very special place [with] the land and the plants. But when I started seriously [taking pictures] in 2003 which is when we bought a house near here, it’s always been just for my enjoyment.

Where else can I go in the morning, and just be by myself?

But eventually Croom’s project attracted notice from the local art community, and he realized that his photographs could serve a greater purpose. While Ed Croom found Rowan Oak to be a quiet sanctuary for him to spend time alone in nature, he noticed it was a similar place of refuge for others. Thousands of families, couples, and University of Mississippi students hike the trail through Bailey Woods, or enjoy a picnic or a book on the Rowan Oak grounds. Croom wanted to foster a deeper relationship between visitors and the individual plants that inhabit the Rowan Oak landscape:

So for my theme, [Rowan Oak] was a place that’s a jewel and had all these aspects in the grounds, that just begged me to show people what this is like so they will see the beauty and the mystery.

There’s a reason that I think students and others come here to study sometimes, there’s no other quiet place they have to come.

When we compare [Rowan Oak] to the rest of Oxford, I think it’s a kind of nature reserve, and historic landscape. All that, right here, there’s no other place like it.

Croom wanted to capture the overall beauty and mystery of the landscape, and also create a private relationship between the viewer and individual plants:

I try to look at [each plant] as a portrait, that’s how I look at them. Even this little periwinkle, that could just as easily be a little person.

And to me it’s as if I could see these plants as they’ve made their place in the ground.

Croom’s photographs encourage the viewer to become familiar with the Rowan Oak landscape and the plants that inhabit it, but at the heart of the Land of Rowan Oak is William Faulkner himself. Croom’s own relationship to Faulkner developed while photographing Rowan Oak:

Now I’ve read many of [Faulkner’s] novels, I’ve read many of his short stories, but I came to know him through this place. [...] There are scenes in his books, even if they were someplace else, he walked past those same scenes or those same plants here everyday.

And so I think Rowan Oak was his muse. It gave him a sense of his own history.

Croom finds deeper meaning in the landscape by questioning how plants are used, why they are cultivated, and how they connect to history and memory.

Faulkner used the grounds around Rowan Oak for hunting, gathering nuts and fruit from the trees and vines, horseback riding, gardening, and writing. In the footnotes to The Land of Rowan Oak, Ed Croom wanted to identify the types of plants he photographed by their scientific name as well as the common name that Faulkner would have used to identify them. Croom also wanted to show how those plants were incorporated into the American author’s fictional landscape, using an extensive footnoted section at the end of the book to interpret his own photographs.

In his introduction to the book, Croom shows how Faulkner’s writing may have been influenced by the landscape of Rowan Oak:

Whether inspired by the plants and land at Rowan Oak or from some other southern location, Faulkner’s writing includes landscapes and plants still found at the home. “It was a summer of wisteria. The twilight was full of it...”; “what vow, what promise, what rapt biding fire has the lilac rain of this wisteria, this heavy rose’s dissolution, crowned?” he wrote in Absalom! Absalom!, expressing an elusive idea or memory with brief, evocative mentions of southern flora. Rowan Oak’s modern-day plants and vistas, which include the photographed flowering dogwoods, wild and cultivated grapevines, southern magnolias, honeysuckle, and the tall native eastern red cedar along the drive and front walk, appear frequently in Faulkner’s writings.

Rather than placing the contemporary landscape of Rowan Oak into a historical or literary context, Ed Croom’s photographs brings each plant to life by giving it a personality. In his book, Croom finds deeper meaning in the landscape by questioning how plants are used, why they are cultivated, and how they connect to history and memory.

Walking the grounds, often in the early morning, I find Rowan Oak a place of quiet contemplation, and yet it is also much else.

It is a place to witness the seasonal beauty of the plants, a living museum and repository of historical garden plants, and a reflection of a writer’s relationship to his personal land.