We often spent time together driving around and I quickly learned that there were She-Wolf rules of the road.

You could describe her music as rhythmic and at times haunting. Often, she matched drone-like guitar chords in one key to the beat of the tambourine she also played with her foot. This style harkened back to Africa—music from Mali, Congo and the Ivory Coast. To this day, if you mix in Jessie’s music with Amadou et Mariam (a blind musical couple from Mali), or any music from West Africa, you would find it almost interchangeable despite coming from different continents.

At that time, I tried to find out as much as I could about her. This was not such an easy feat before the era of the Internet, but I discovered that she was still alive and living in her native North Mississippi. This discovery was ultimately a catalyst for my move to New Orleans, for I felt compelled to seek her out. I had no clue what I was getting into, or where this would lead me.

Jessie came from a musical family in the Hill Country led by her paternal grandfather, Sid Hemphill, who Alan Lomax dubbed “The Grandfather of Hill Country Blues.” Sid was known for his homemade instruments, fife-and-drum music he composed and played with his string band. These songs usually told the story of the goings-on around the hills and countryside of his home, as well as old folktales and legends like John Henry, or the pesky Boll Weevil. He was a popular entertainer at picnics and was recorded by Alan Lomax during his 1942 fieldtrip to North Mississippi for the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song. Those recordings, now repatriated and available to explore along with photographs of the sessions at the Senatobia Public Library, are the very core of what Hill Country blues was and has evolved to be over time. Sid and his daughters Rosa, Sidney, and Virgie had a fife-and-drum band and Rosa was also a skilled blues guitarist. Jessie always said that her grandaddy taught her everything she knew.

Growing up in this environment and playing the picnics with her family was the foundation in creating the singer-songwriter and talented guitarist who ultimately became She-Wolf. Jessie Mae had several alter egos, but She-Wolf (also the title of her 1981 debut record) was the favorite. Although wolves are known to be pack animals, mythology cites the she-wolf as a determined huntress, nurturer, and survivor.

Jessie had no peers or other female contemporary musicians or guitarists she learned from or was inspired by; though it is possible she heard a few recordings of Memphis Minnie in passing. I wouldn’t doubt that, because if there was ever anyone similar to Jessie, it would be Memphis Minnie. They were both independent women out there in a man’s country blues world. There were male players like R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough, whom Jessie knew and performed with, though she was the lone She-Wolf.

There is nothing like being yelled at by Jessie Mae Hemphill.

In many ways, Jess became a grandmother figure in my life. She had a lot of wisdom and plenty of experience in her to share with this young white girl in New Orleans. Once I found her, we often spent time together driving around and I quickly learned that there were She-Wolf rules of the road.

One of her big mandates was about the right way to do railroad crossings. Coming from the city, I was used to crossing lights and barricades—wait until they they lifted, quickly look both ways, and then keep rolling if all was clear. On a drive with Jess, I proceeded across a railroad crossing the way I had always done since I started driving at 16. She yelled so loud I nearly jumped out of the sunroof of my car. She thought I almost killed us because I did not stop first, look both ways for trains—wait about 20 seconds more— look both ways again, and then cross over real fast. “Trains come hauling out of nowhere with no warning and kill people all the time,” she’d say.

There is nothing like being yelled at by Jessie Mae Hemphill. To this day, whenever I cross train tracks, I can hear her yelling She-Wolf directions at me.

Jessie had a hot red Cadillac she was very proud of parked in her driveway and occasionally she’d ask me to crank it, let it run a little and then cut off the engine. One early afternoon in the fall, she decided we were going to go for a drive, but this time she would take the wheel and drive the Cadillac. Honestly, I don’t recall the exact thoughts I had at hearing this declaration, other than a slight pang of terror and some disbelief—but there is no arguing with Jess when her mind is made up. The thought of having her drive us was daunting considering that she had a stroke 10 years prior to us meeting, leaving her paralyzed on her right side. Knowing this, it was a little surprising that she still held a valid driver’s license. But hey, what did I know? On the strength of her convictions, I decided to hope, hold tight, and hang on.

On the strength of her convictions, I decided to hope, hold tight, and hang on.

We managed to back out of her driveway and creep out of the trailer park where she lived, without incident. The turn onto the frontage road was also not too terribly eventful other than a few honks. She was not a fast driver. In fact, we were passed by several annoyed motorists, though this did not trouble me much at the moment. She did not tell me where we were going, we were just going. I soon realized we were cruising on Highway 4 heading west on our way to Who-Knows-Where. I saw the sign for Strayhorn, so I mused we were heading there because she wanted to see something—or someone. As soon as I settled on Strayhorn as our imagined destination, Jessie changed directions.

Jessie had somehow learned to drive with her left hand and foot to compensate for her right side being paralyzed from her stroke. This made a U-turn impossible. She found a nice long driveway she thought would do nicely for making a turn. She pulled into the driveway and kept on driving. All the way up. We suddenly approached a house, with its inhabitants sitting on the porch and enjoying a relaxing afternoon, or so they thought. Since Jessie could not U-turn, we began to make a big circle right through their yard, running over plants, a kiddie pool, toys, and whatever random things were in the path of She-Wolf’s Cadillac. The homeowners were none too happy about this disturbance. The head of household jumped up and came running down the steps of the porch towards us. I gripped the door handle tight in anticipation of how this scene would go down. We must have been some sight—a determined and hollering old lady and wide-eyed and petrified young girl in a big, red Cadillac plowing through his yard.

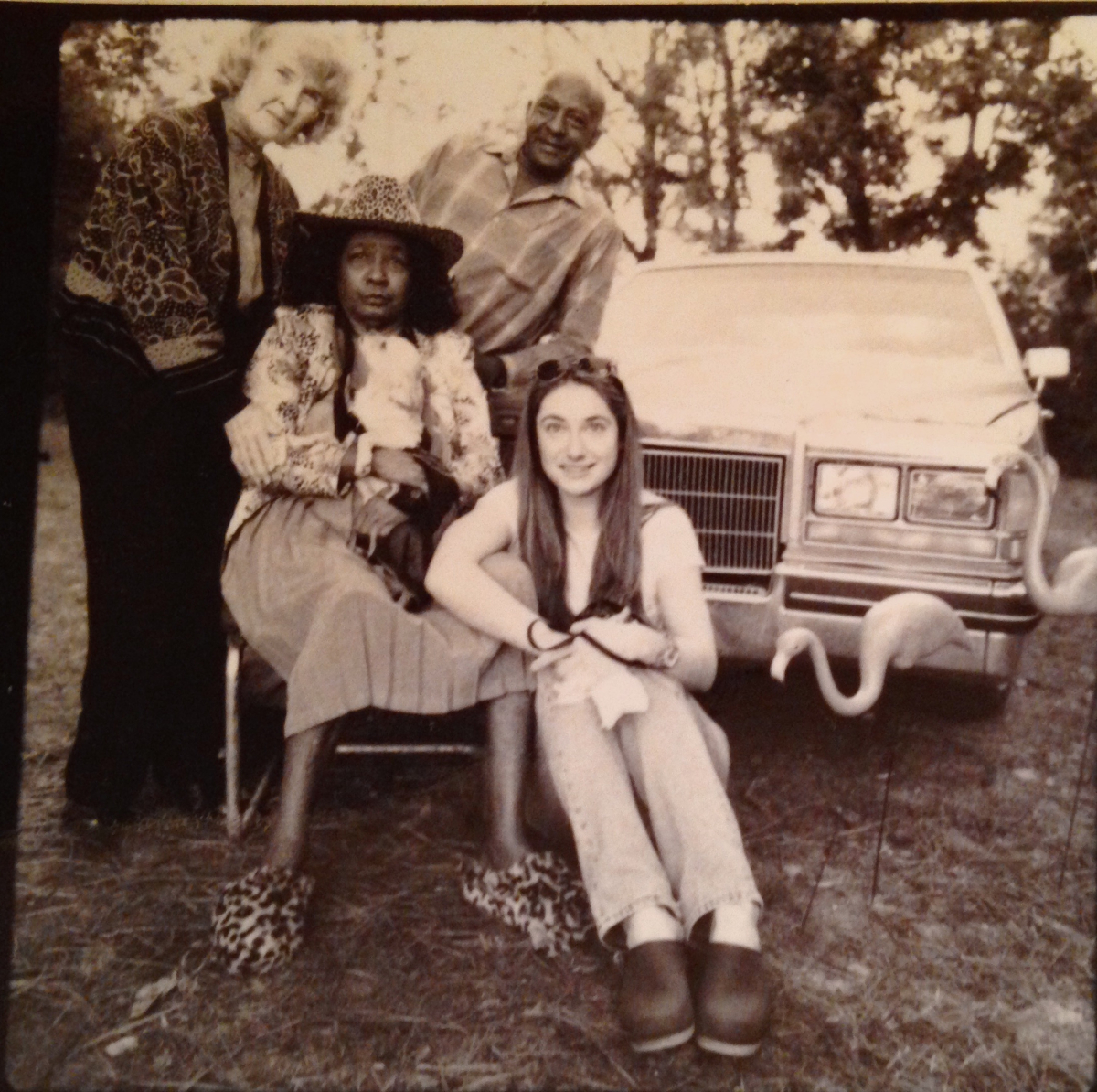

Jessie Mae and Olga with friends on their shared birthday, October 18, 2001. Photo by Steve Gardner.

Jessie suddenly got nervous (I was already panicked), and she hit the gas hard. We peeled out that yard like bank robbers on the run, kicking up a cloud of dirt while roaring back down the driveway leveling anything in our path. She didn’t bother to look both ways this time, ignoring her own She-Wolf rule as we tore a left turn onto the highway headed east at alarming speed.

We rode on in silence for a while, out of breath, thankful, and bewildered. Once we got some distance behind us and Strayhorn, she relaxed a bit and declared that maybe her story will still be on the TV when we get back. Her favorite “story” was The Guiding Light, which we watched every day together (she enjoyed yelling directions at the characters), the title of which seemed ever fitting on this day.

After her stroke, she was still She-Wolf. She was still passionate, fierce and determined to make it her way, whichever way it was. And she did.

Looking back and thinking about this, and other times we shared, I realized our meeting and connection was far beyond what either of us knew at the time. And yet somehow we knew that there was something more for us to do together, and that time would reveal those purposes and continue to do so, even after her passing.