Introduction

In the wake of 9/11, Willie King & The Liberators recorded the song “Terrorized,” which placed the seemingly new state of political reality in historical perspective. “You talk about terror/People, I've been terrorized all my days,” sings King in the opening stanza, and over the next eight minutes he addresses the countless acts of terror faced by African Americans over the centuries—“You know you took my name, and you know you left me in chains,” “You wouldn’t let me go to school, you know I couldn’t read or write,” and “You know they hung me from the tallest oak tree/Well, you talk about terror, I’ve been terrorized all my days.”

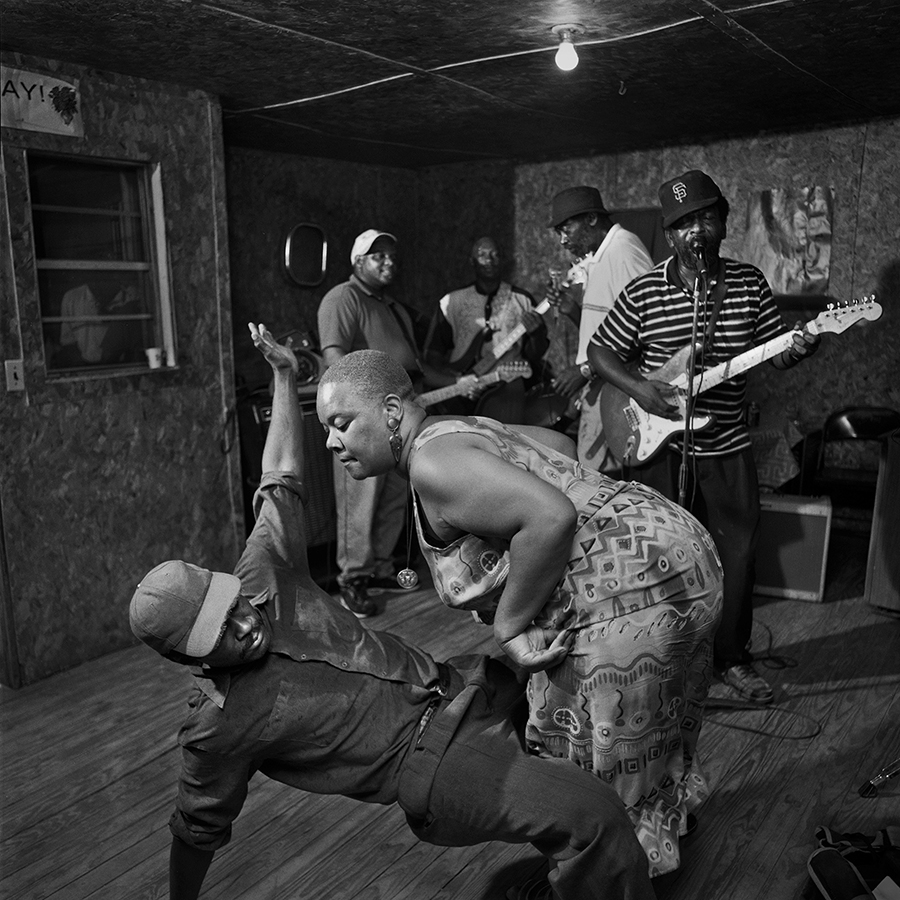

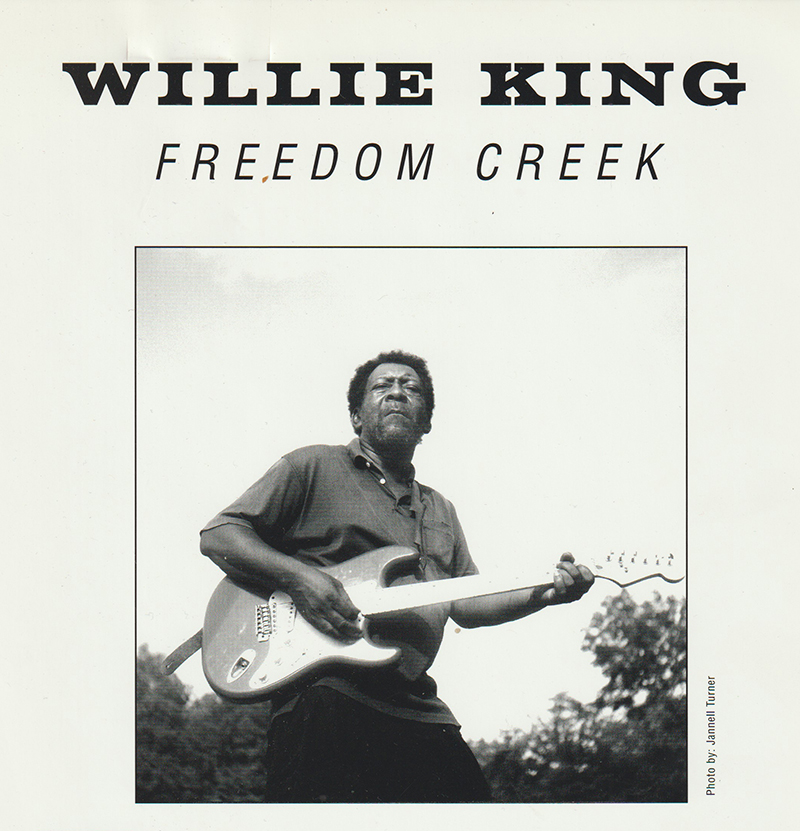

The song was released on King’s 2002 album Living in a New World, which along with Freedom Creek from 2000 (both issued on Rooster Blues) introduced King’s politically-charged blues to an international audience. His fearless approach to issues of racial oppression might appear relatively novel for the blues, stereotypically known more for songs about romantic troubles. The appeal of King’s music, though, extended beyond his earnest lyrics. His songs also had a raw and infectious musical character that had much to do with King playing them regularly for dancers at Bettie’s Place, a juke joint in rural Prairie Point, Mississippi.

By the time King (1943-2009) recorded these albums he’d been engaged with protest songs—what he called “struggling blues”—and political activism for several decades. While some songs—such as “Terrorized” and “Is It My Imagination (Looks Like I’m Still On That Plantation)”—addressed general issues of oppression, others commented on specific grievances in Pickens County, Alabama, where King lived most of his life, and across the Tombigbee River in Noxubee County, Mississippi, where he was born.

“If you don’t participate in the blues then the blues will ride you,” said King.

Blues was King’s platform for expressing his vision of social justice, and he was also adamant in testifying about how engaging with blues music was necessary to help alleviate problems associated with “the blues,” the melancholy emotional state. King was not unique in pointing to the cathartic qualities of blues music, but was particularly eloquent in describing its social necessity and sacred origin.

“If you don’t participate in the blues then the blues will ride you,” said King. “No matter where you come from, or how much money you have. They will take you under. But, now, you participate in the blues, it will help get the blues off of you, help get that worry off of your mind.” 1

Musical Upbringing

Willie King was born on March 18, 1943 in Prairie Point, Mississippi, and grew up moving from plantation to plantation with his mother and her parents. His grandfather sang gospel and blues and his grandmother ran a juke joint, and it was there King first saw blues performed live. His first instrument was a homemade one-string “diddley bow,” and at 13, he acquired his first guitar through the plantation owner, W.P. Morgan, who King recalled, was surprisingly supportive of his desire to no longer work in the fields after turning 16. Instead, King took on various odd jobs, and for a decade made moonshine.

King began developing his musical skills around 16, studying local blues artists including Jessie Daniel, Milton Houston, and Birmingham George Conner. King made his debut performing at twenty.

“I didn’t know but two songs at the time, two Jimmy Reed songs— “You Don’t Have to Go” [and] “Going to Get My Baby”—that’s the two I had. I started out by myself on acoustic. I made my first debut over in Mississippi at a little houseparty they had, they had nothing but lamp lights. Gambling in one room, trying to dance to the blues in one room. And I played all night and got two dollars, played till the sun rose the next morning. Had a guy singing for me, and I was on them two tunes. Oh yeah, it worked, man. They wanted me back. And I kept working, I got me a few more tunes. I kept building my repertoire so I started getting into a little Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, those type of guys.”

"And this name that he gave me means 'servant of God.' That means you have to try to do the right thing all the time."

In 1967 King moved to Chicago for eight or nine months. Instead of finding the good life that friends had promised, King was disturbed by the high levels of crime and poverty there and longed to return home. Once back in Pickens County, he began reassessing the social conditions around him and rethinking his relationship to the blues. In doing so he drew upon early life lessons from his grandfather, a Muslim who secretly gave King the name “Abdullah.”

“My grandfather, he was Muslim. Back then he used to take me out in the woods and used to talk to me about it. He told me, ‘Now you can’t let them know about it right now,’ but he told me that there was gonna come a day when I wouldn’t have to hide it. And this name that he gave me means “servant of God”. That means you have to try to do the right thing all the time. I’ve taken it to heart. Help people, respect people, love people, try to help them in any way. So, that’s my reputation.”

King credits local musician Albert “Brook” Duck with teaching him the “secret code” of the blues.

“At the time you couldn’t just come out and talk about the whites, how they was doing you, how they was treating you, knowing that they wasn’t treating you right. So you had to use this woman for to get your message across. [Sings] ‘Oh, she ain’t treating me right.’

“But most of the time you’re talking about the woman and the bossman. But you’ve got to use the woman for to try to keep everything in peace. You just couldn’t come out and say that your bossman wasn’t treating you right. Even in some games they play, they’re talking about the white man. They use different kinds of animals, ducks, geeses, chickens.”

Although King didn’t start writing his own explicitly political blues until the early ‘80s, he began performing political songs that he encountered through commercial recordings.

"We all knew that this wasn't supposed to happen in America, that all we wanted was simple justice.”

“I was singin’ some of the old guys’ blues, like Lightnin’ Hopkins’ political songs, like when he was down on Mr. Tom Moore’s Farm, 2 some Howlin’ Wolf—’Coon On The Moon’, [sings the lyrics] ‘You gonna wake up one morning, and there’s gonna be a coon on the moon. You gonna wake up one morning, and there’s gonna be a Black man who’s president.’”

“Coon on the Moon” was issued as a Howlin’ Wolf single by Chess Records in 1973. The lyrics, by his saxophonist Eddie Shaw from Benoit, Mississippi, also makes references to school integration, George Washington Carver, and pioneering Arctic explorer Matthew Henson.

King formed the Liberators in the mid-‘70s and gained a broader audience after playing in 1976 at the Black Belt Folk Roots Festival in Eutaw, Alabama, founded in 1975 by social activists and folklorists Jane and Hubert Sapp as an outgrowth of work they conducted at Miles College-Eutaw. Carol Zippert, who operates the festival today, recalls that King was already performing topical songs at that first show.

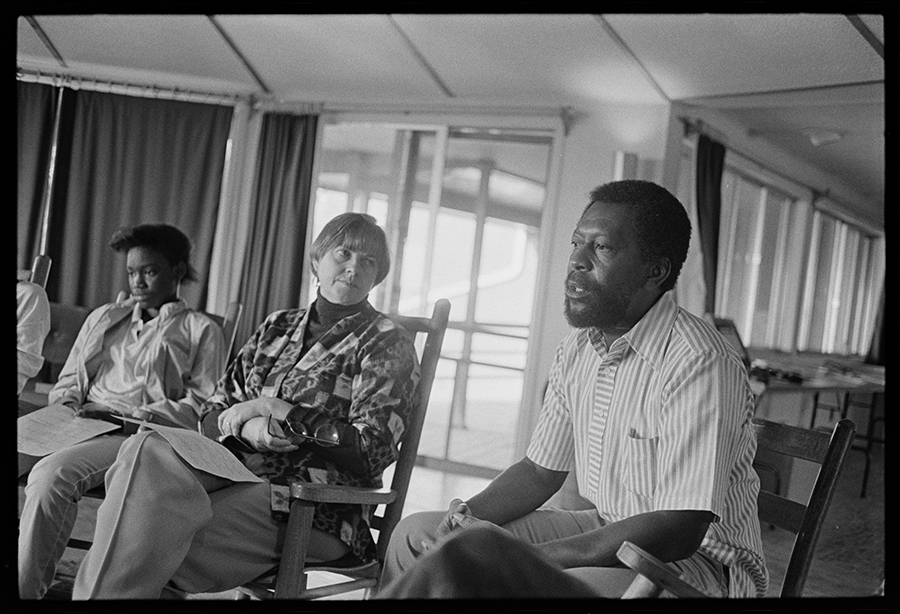

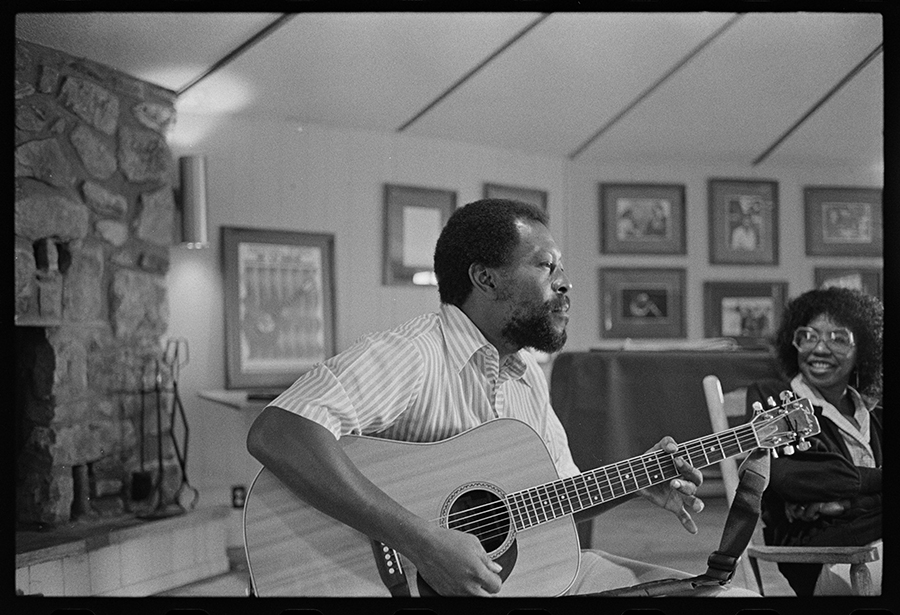

Highlander

King’s political consciousness was heightened after Jane Sapp brought him to the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee, where Sapp served as the Cultural Program Coordinator from 1983-89. Highlander, founded in 1932, played an important role in the civil rights movement. It was there the traditional spiritual I Shall Overcome was reworked into the civil rights anthem We Shall Overcome, that Rosa Parks attended a workshop on desegregation prior to her arrest in Montgomery for refusing to change her bus seat. Musical directors Guy and Candie Carawan taught many civil rights activists about freedom songs in the 1960s.

“I used to go up to the Highlander three or four times a month,” King recalled. “Guy Carawan, he used to get me to come up there. I think I was some kind of inspiration. ‘Cause I was singing out on a lot of problems that was happening and I begin to realize that we all was having the same kind of problems, a lot of the same problems that we’re having today.

“A lot of people—Martin Luther King [Jr.]—have been through Highlander. Pete Seeger, I played with him way up in Boston. We talked, and we did a closing song together, worked on it and got the music together. Great big church. That was the first time I cried, I couldn’t help it, by playing music. The people just stood up, man, gave me a big round of applause. Good God Almighty, man, I felt the power. That really inspired me to keep on.”

“He was a very important part of Highlander’s cultural work in the 1980s,” recalled Candie Carawan recently via e-mail. “He came to many workshops at Highlander and was very generous with his music and his reflections about his life and experiences. I know many workshop participants were moved and influenced by his presence (Including us!).”

"Pete Seeger, I played with him way up in Boston. We talked, and we did a closing song together, worked on it and got the music together. Great big church. That was the first time I cried, I couldn’t help it, by playing music."

Folklorist Bill Ferris attended a workshop with King during a visit to Highlander, and has strong memories of political song workshops led there by Mississippi civil rights veteran, Hollis Watkins. “We sat in a circle of rocking chairs,” recalls Ferris, “and there was a linking in the circle both physically and in terms of the spoken and sung works. Hollis Watkins would start talking and that talk would flow into song. It was so beautiful.”

An organizer for SNCC in the 1960s, Watkins taught activists how to integrate song into their political campaigns, which both increased their effectiveness at spreading their messages and helped keep them mentally positive.

“Singing was the tool that let people get more active when they are downhearted and down in spirit. The next thing you know the energy level is up and they’re ready to move forward,” said Watkins.

Watkins also noted Highlander’s importance for networking. “Highlander was a place where activists who didn’t [regularly] see each other went, a place where you could keep up with what other people were doing.”

In an interview with journalist Geoffrey Himes, King said, “At Highlander I met a lot of people having the same problems we were, from coal miners to sharecroppers. We all knew that this wasn't supposed to happen in America, that all we wanted was simple justice.”

Political Songs and Activism

King recalled that his real entrance into composing original political songs stemmed from a political issue in Pickens County in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

“Well, I call them struggling songs. I got started with it down here in Aliceville. We was protesting on these two ladies, Miss [Julia] Wilder, Maggie Bozeman, here in Pickens County that they accused for voter fraud. But what they really didn’t like that they was going around getting people signed up to vote. A lot of the whites around there, they just couldn’t stand that. 3

King credits Birmingham-based civil rights attorney David Gespass, who represented Wilder and Bozeman, with inspiring him to write songs about specific political issues.. “He wrote that one [on Freedom Creek] about Pickens County—[sings a stanza] ‘If you Black, living in Pickens County, trying to stand up for your rights, you got to put up a hell of a fight’—for us. He said, ‘Well, I ain’t got no money to help y’all but I can give y’all a song.’”

“And that reflected back upon what my grandfather had taught me, that I always have to use what God give me. That I was blessed. He tried to influence me to stand and be a man. And to always try to be creative, to help yourself so that you could help somebody else.”

One of King’s first “struggling blues” song was Uncle Tom, a response to local African Americans who reported his civil rights actions to the authorities. “What happened there, the sheriff, he was working a lot of peoples in jail, putting them on different plantations, and he was keeping the money.” King and another social activist photographed the labor camps, and by the time they arrived back in town they were stopped by the police.

Blues scholar Jim O’Neal, who recorded Freedom Creek and Living In a New World, first encountered King at the Black Belt Roots Festival in Eutaw in 1987, and was impressed with his performance there of King’s political songs.

“He was always making songs about what was going on. I remember one of the songs that I heard at a festival [featured the lyrics] ‘We the people have the power to stop child sexual abuse.’ I think he said the child’s name. But he had very powerful songs and he wasn’t afraid to speak his mind.”

Back in King’s home community O’Neal observed that, “He would stop at people’s houses and I saw what a community organizer/activist he was. He would help people register to vote or with other issues, kind of like [bluesman Jimmy] Duck Holmes did in Bentonia—a go-to person who people would come to for help, because he knew what channels to go through.”

In addition to his more conventional political work, King channeled his energies into working with local youth, instructing them on “the basics.”

“[We] teach them about their heritage, and how to survive, survival skills. Along with the music, we show appreciation to the Lord for sending us the wild berries, wild plums, figs, pears. It helps to kind of settle their mind.”

His main outlet for such work was as the leader of the local Rural Members Association, and he also worked with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, which assists farm workers of color, and the non-profit Alabama Blues Project.

King also started the longstanding Freedom Creek Festival near his home in Old Memphis, Alabama, which became a popular destination after the release of Freedom Creek in 2000. Creeks were an important metaphor for King, who noted their importance in rural culture— for fishing, bathing, watering animals, and baptism, and he became financially independent making moonshine in creeks.

Willie King’s death at 65 on March 8, 2009 was a major loss to blues fans and his beloved community of Old Memphis, Alabama, but his years of proclaiming the gospel of the blues have had a lasting impact. His musical and political legacy is carried on by his students including Jock Webb, who fights for the rights of farmers of color and plays harmonica with the band led by Greenville, Mississippi's Keith Johnson, as well as the bands led by former Liberators Willie Lee Halpert and Debbie Bond.

King’s years in the national and international spotlight following the release of Freedom Creek also raised consciousness about the blues traditions of the Black Prairie region of Mississippi and Alabama. They’re now celebrated annually at the Bukka White Blues Festival in Aberdeen and the Black Prairie Blues Festival in West Point, where a Black Prairie Blues Museum that will honor King and others from the region is planned.

Resources

Barretta, Scott. "Willie King: Backwoods Philosopher of the Blues," pp. 24-33 in Living Blues, issue 154, November/December 2000

Carawan, Candie. Email correspondence, May 12, 2021

Ferris, William. Telephone interview, March 15, 2021

O'Neal, Jim. Telephone interview, March 13, 2021

Watkins, Hollis. Telephone interview, March 25, 2021

Links

Himes, Geoffrey. "Musician Willie King mixes politics with blues," Chicago Tribune, June 21, 2002

Footnotes

- ^ The source for all quotes by Willie King in this article can be found here: Barretta, Scott. "Willie King: Backwoods Philosopher of the Blues," pp. 24-33 in Living Blues, issue 154, November/December 2000.

- ^ Moore was a plantation owner near Navasota, Texas who was infamous locally for his brutal labor practices. Hopkins initially recorded the song in 1949 as “Tim Moore’s Farm” to avoid reprisal, and later as “Tom Moore Blues.”

- ^ Both were imprisoned but the convictions were reversed following major protests.