The photos in this essay document an important civil rights victory in Port Gibson, Mississippi in 1982

During the 1960s, organizers in the civil rights movement saw a need to motivate, inspire, and protect people who, at great personal risk, were demanding their rights as U.S. citizens. Close at hand was a familiar institution that had nurtured the Black community through years of enslavement, war, reconstruction, and Jim Crow restrictions: the Black church. Many of the rituals that characterized the Black church are ancient and derive from older religious practices: rituals such as meeting, preaching, singing, and marching or parading in the service of their beliefs and aspirations, and eating together to express their union. Throughout the American south, civil rights leaders used mass meetings, often in churches, to inspire their fellow workers with preaching and singing; and marches to display their unity and determination. This photo essay seeks to show how one Black community used these familiar rituals not only to organize the fight but also to celebrate an important civil rights victory. But first, some history to set the scene.

Throughout the American south, civil rights leaders used mass meetings, often in churches, to inspire their fellow workers with preaching and singing; and marches to display their unity and determination.

Historical Context

The Black citizens of Claiborne County, Mississippi, after years of being denied their political and civil rights, found new hope for change in the 1960s amid the stirrings of the civil rights movement. White political leaders, bankers, and businessmen in Port Gibson, the county seat, found something else: a will to resist any change that threatened their control over the political and economic life of the town. Countywide, Black residents outnumbered white residents 80 percent to 20 percent. White citizens had money and the whole apparatus of Jim Crow repression on their side; on the other side, Black citizens had numbers, a rising tide of national outrage over racial attacks, and an embryonic federal push to help Blacks register to vote. The result was an entrenched battle that could have been avoided if white leaders were willing to begin reforms in good faith, but they were not. Attempts to meet and settle differences got nowhere, and Blacks, under the auspices of the NAACP, began holding mass meetings and marches in support of their grievances.

The board members of the local chapter of the NAACP sent letters in March, 1966 to white leaders and public officials listing their demands: jobs for Blacks as clerks and cashiers in local businesses; desegregation of all schools and public facilities; integration of city police and county sheriff’s deputies with Black officers given full police power to arrest whites; employment of Blacks in the welfare office and their addition to all boards and commissions; and (perhaps the most symbolically important of the demands) the extension of courtesy titles to all African American citizens. 1

...[M]ass meetings and marches had spread Black courage and confidence that they had economic power in a small town where white merchants depended on Black spending to keep their businesses profitable.

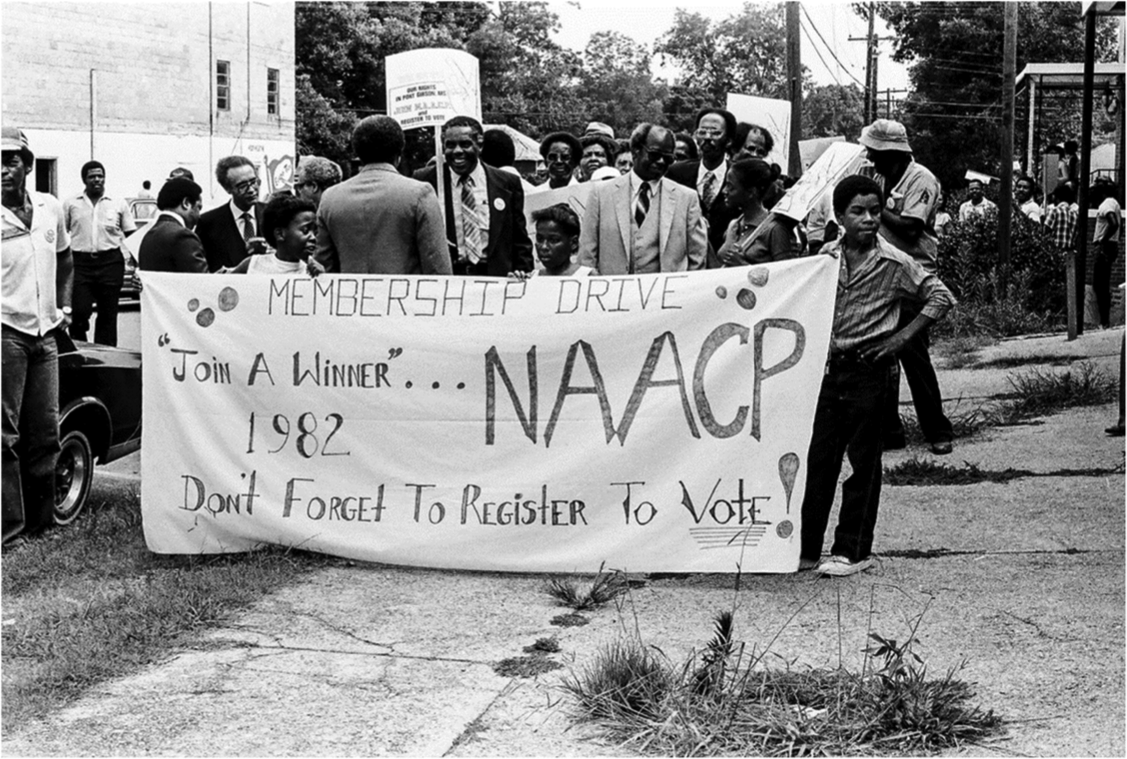

White leaders in Port Gibson resisted the demands, denying that the NAACP represented the true wishes of the local Black citizens and believing that they could outlast this wave of activism by doing nothing. They either did not know or did not appreciate two powerful weapons that the protestors had on their side. NAACP organizer Rudy Shields had been enlisting local activists to carry out a voter registration drive in the county, and, with federally appointed registrars, they had increased the number of Blacks registered to vote to a majority of all potential voters. Also mass meetings and marches had spread Black courage and confidence that they had economic power in a small town where white merchants depended on Black spending to keep their businesses profitable.

While the NAACP board did not specifically threaten the whites with election losses or with a boycott of businesses, they did suggest that whites could avoid these tactics only if their leaders negotiated in good faith and set up timelines for implementation of reforms. The white leaders again refused, and at the next mass meeting, the NAACP chapter called for a boycott of white-owned businesses, beginning at noon on Friday, April 1, 1966. At that time Charles Evers led over 450 protesters from First Baptist Church to the County Courthouse to announce the imposition of the boycott.

This boycott created a virtual wall that divided the town between warring factions. The conflict lasted, with greater and lesser intensity, for over a decade. Whites joined together to fight the boycott with manpower from local and state law enforcement, and strategy from the anti-movement organizations such as the white Citizens’ Council and the state Sovereignty Commission. Employers and landlords threatened activists with firing and eviction. Black activists picketed affected businesses at peak shopping days and times, recruited enforcers to confront Blacks who crossed the picket lines, and formed self-defense units to discourage white attacks on movement activists.

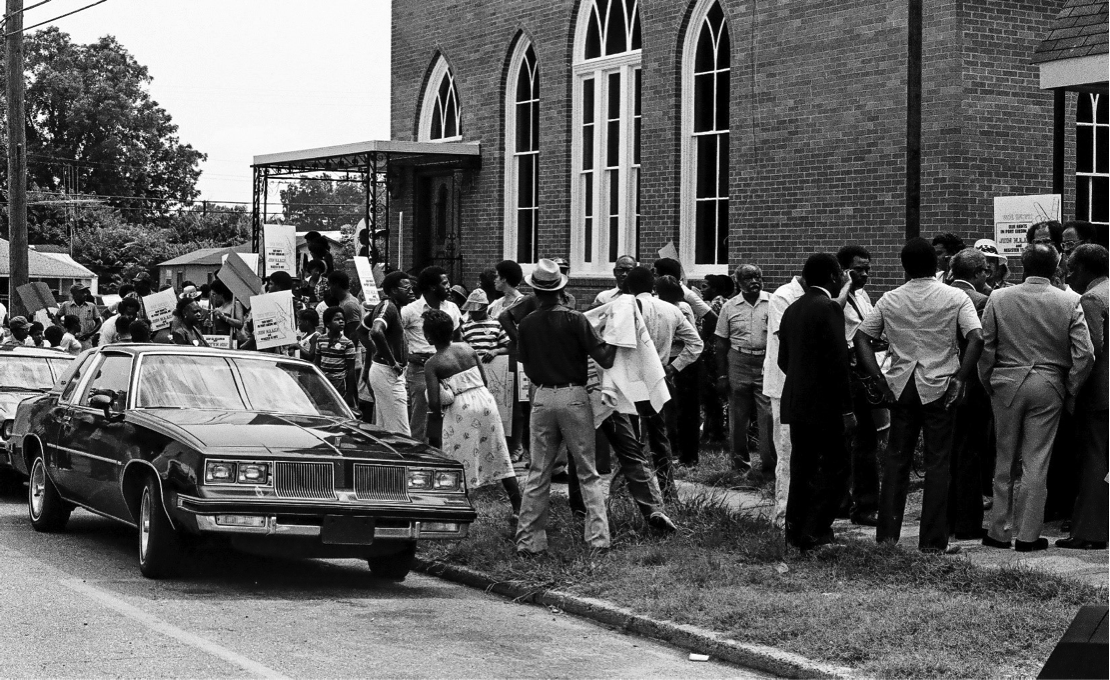

To keep their eyes on the prize during that tumultuous time, Black protesters held mass meetings in churches to hear exhortations from preachers and orators, to sing together, to march, still singing and chanting, from their churches to important civic venues such as courthouses, banks, and mercantile establishments—all this to make known their determination to resist injustice.

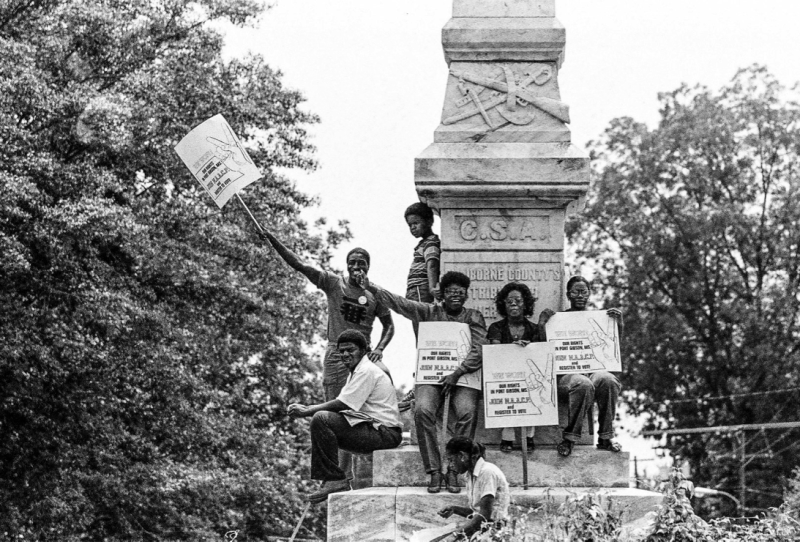

In 1969, a group of white merchants sued the NAACP and local boycotters, seeking an injunction and damages for lost business. The Mississippi Chancery Court ruled in 1976 that the boycott was illegal and ordered the defendants to pay the merchants $1.2 million in damages. To appeal the ruling, the NAACP had to raise a $1.2 million bond to cover the damages if they ultimately lost, and the defendants faced liens against their property. Finally, in 1982 after years of judicial wrangling, the US Supreme Court reversed the judgment, and in a precedent-setting decision, upheld the right to boycott for political reasons, and ordered the plaintiffs to pay the defendants’ legal fees.

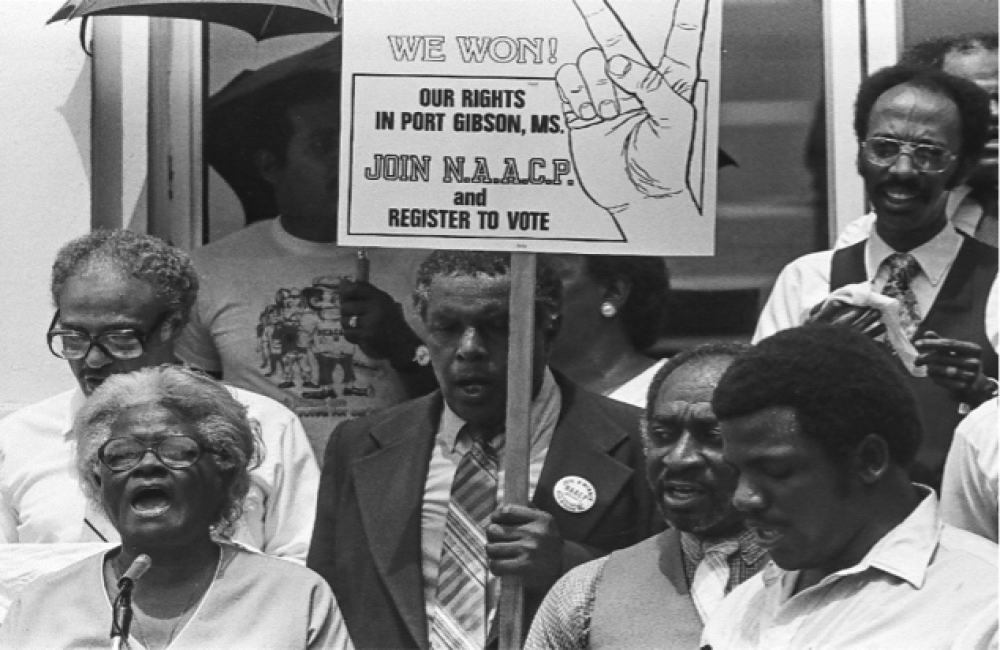

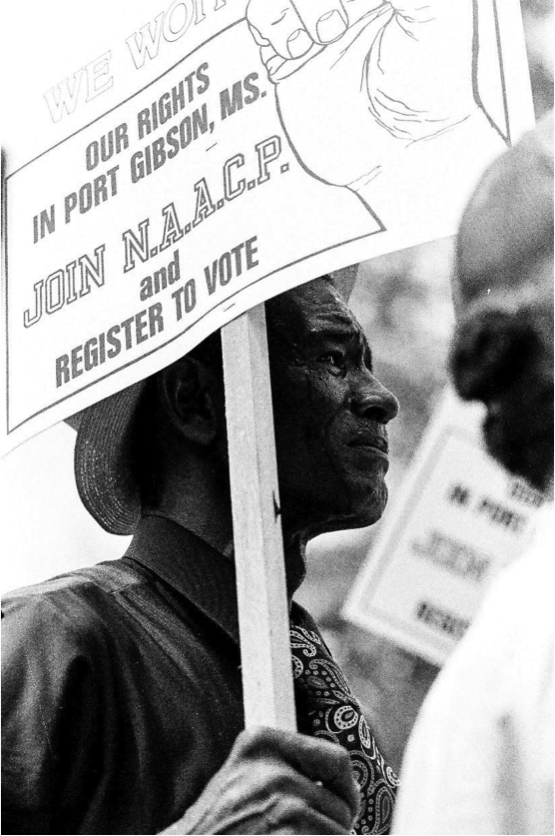

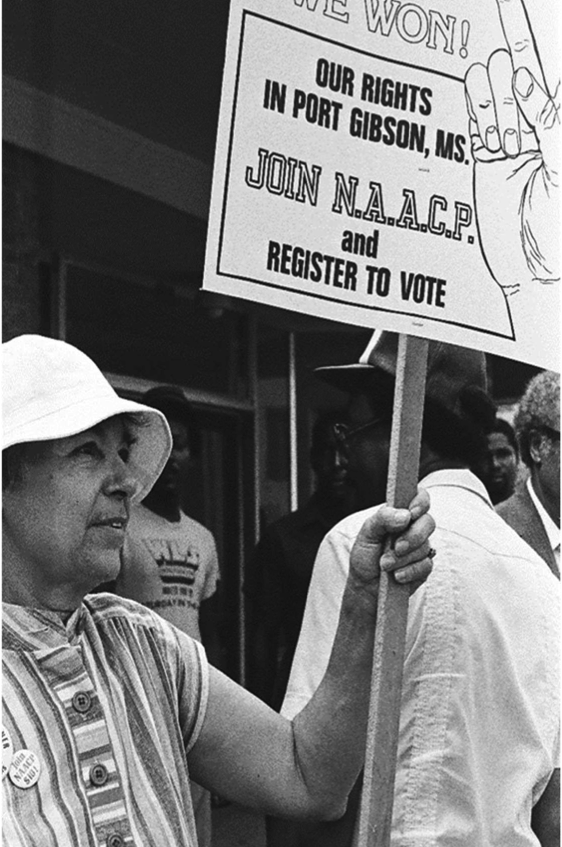

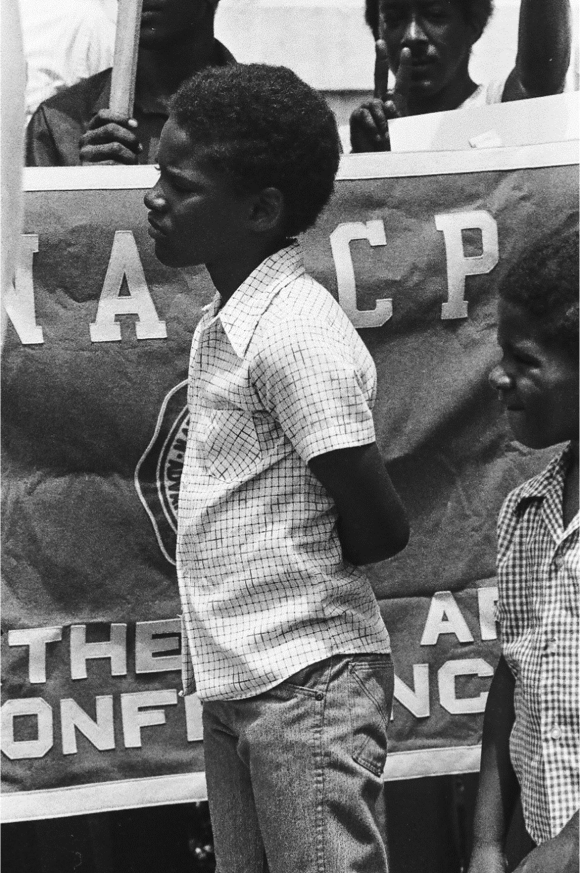

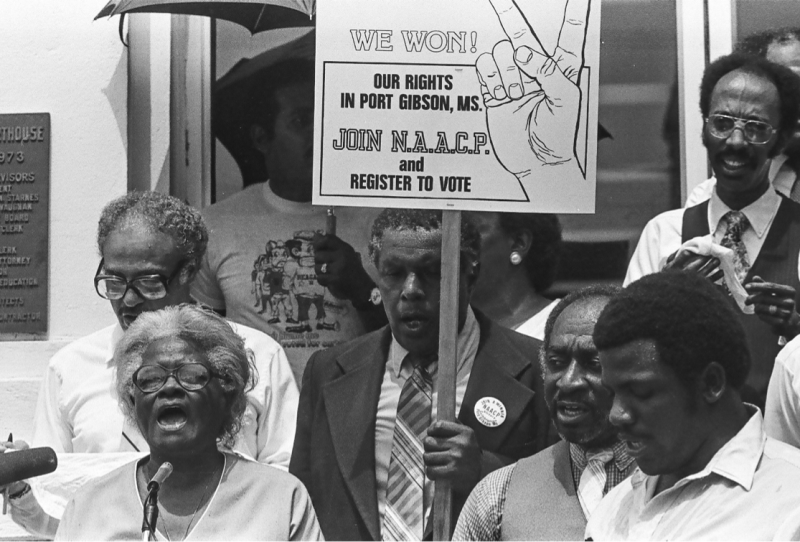

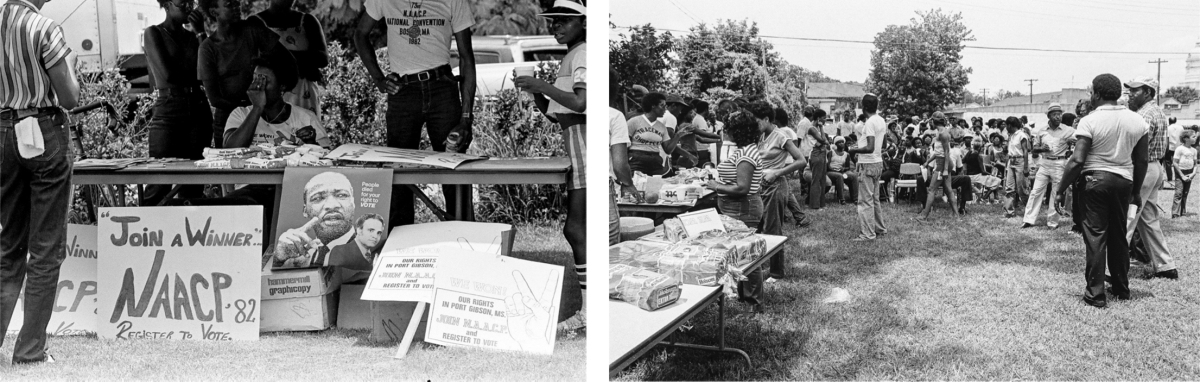

The NAACP proclaimed a day of jubilee on July 29, 1982. National and state leaders joined local people to meet, to sing, chant, and parade to the Courthouse, many of them carrying signs like picketers.

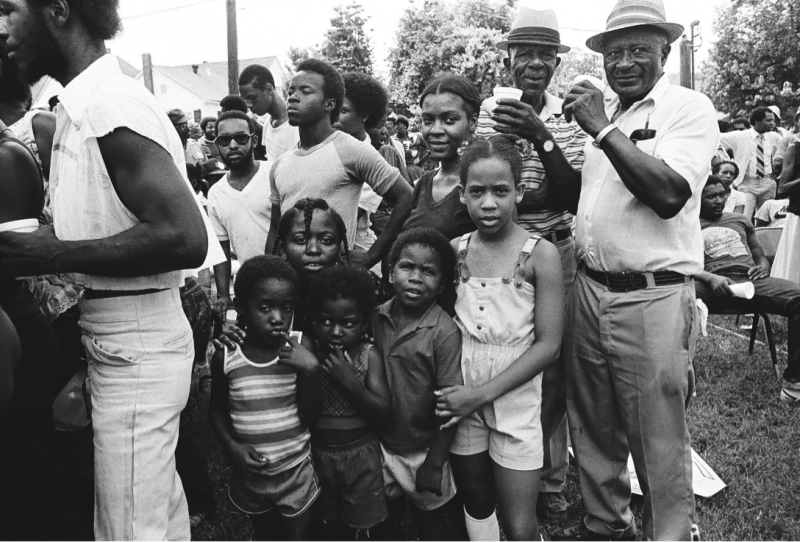

It is not then surprising that when Blacks in Port Gibson won a significant civil rights victory for themselves and for the nation, they expressed their joy with some of the same rituals. The NAACP proclaimed a day of jubilee on July 29, 1982. National and state leaders joined local people to meet, to sing, chant, and parade to the Courthouse, many of them carrying signs like picketers. They applauded and cheered for the speakers, and they arranged a picnic on the grounds. Finally they met together at the church to give thanks.

Photo Essay

On that hot, steamy, typical July day, my wife, Patty was privileged to witness and photograph the celebrations. Here are a few of the images that her camera caught that historic day. Patty and I are grateful to our daughter, Emilye Crosby, for being with her then and for reading drafts of this manuscript to help us get right the historical facts surrounding the boycott. Also to our daughter, Sarah Campbell, for reaching out to her many contacts among the people of the Claiborne County community, and to James and Carolyn Miller and Geraldine Nash for helping to identify many of the persons present that day. If we did manage to get things wrong, they are not to blame.

Churches seemed like a natural choice for mass meetings, which were “structured in a traditional way, almost like a church service, but there was freedom, the word ‘freedom’ instead of a religious reference” (Crosby 106). The celebrators greeted one another, picked up signs and banners as they had done during the movement days, and began a march through town.

It was their determination to claim the streets and sidewalks of the town that paved the way for the freedom of access to public places

they enjoy today.

The celebrators greeted one another, picked up signs and banners as they had done during the movement days, and began a march through town.

Thelma Crowder Wells...was a movement stalwart and defendant in the lawsuit. When she first tried to sing “Amazing Grace” at a rally, she was afraid. “Oh, I was trembling, scared and crying. But I led the hymn, and the people sang it. And on and on my fear went away"

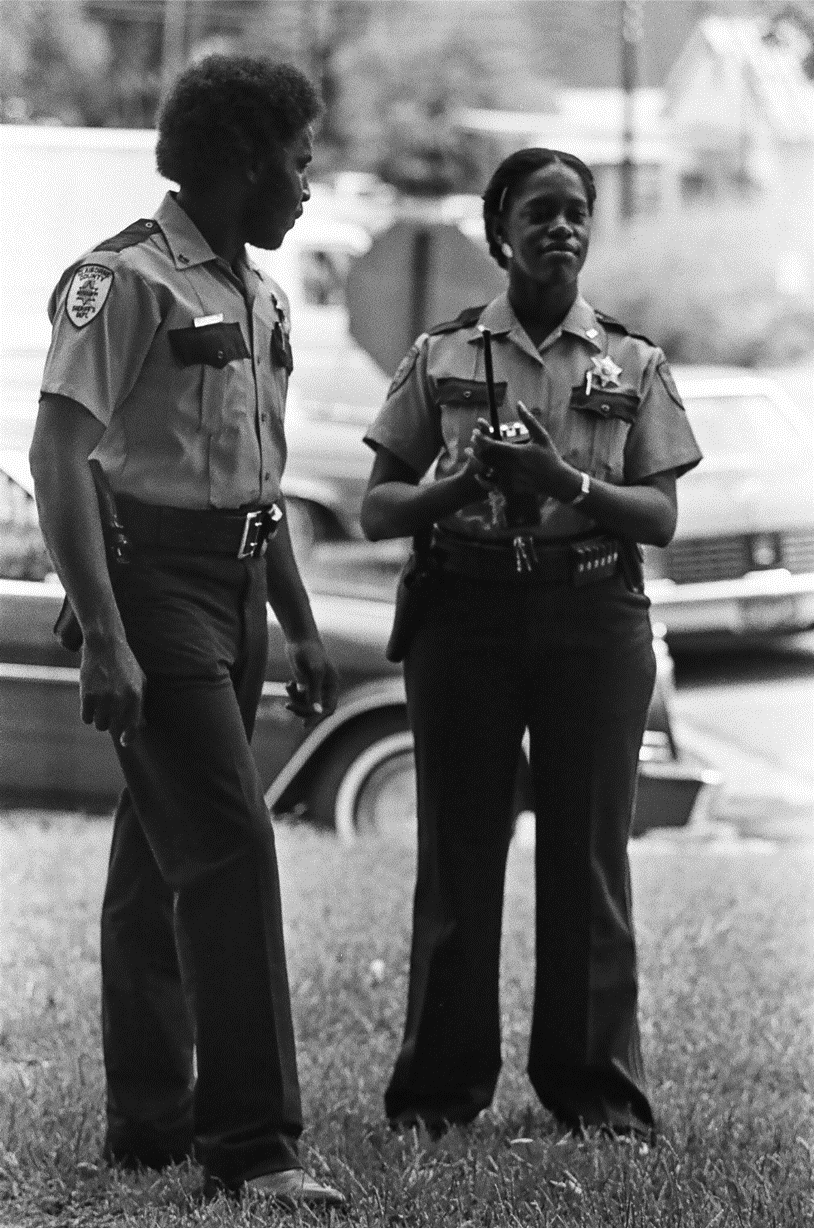

On duty sheriff’s deputies Freddie Yarbrough and Shirley Hall mingled with the celebrating community on the day of victory. One of the movement’s major goals was Black representation in law enforcement. It was intensified when a white man shot and killed an unarmed man, Roosevelt “Dusty” Jackson in April 1969, leading to a rejuvenation of the boycott. Earlier Black officers were appointed by white leaders and had no authority to arrest whites, but the situation had changed when a Black sheriff had been elected. On this day, the police were not afraid of a Black crowd and the crowd was comfortable with the deputies.

Resources

Crosby, Emilye. A Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi. University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Links

Rozier, Alex. “Why a Confederate monument endures in majority-black Port Gibson, Claiborne County.” Mississippi Today, October 3, 2018, https://mississippitoday.org/2018/10/03/why-a-confederate-monument-endures-in-majority-black-port-gibson-claiborne-county/, Accessed May 10, 2021.

Footnotes

- ^ Emilye Crosby, A Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 112.