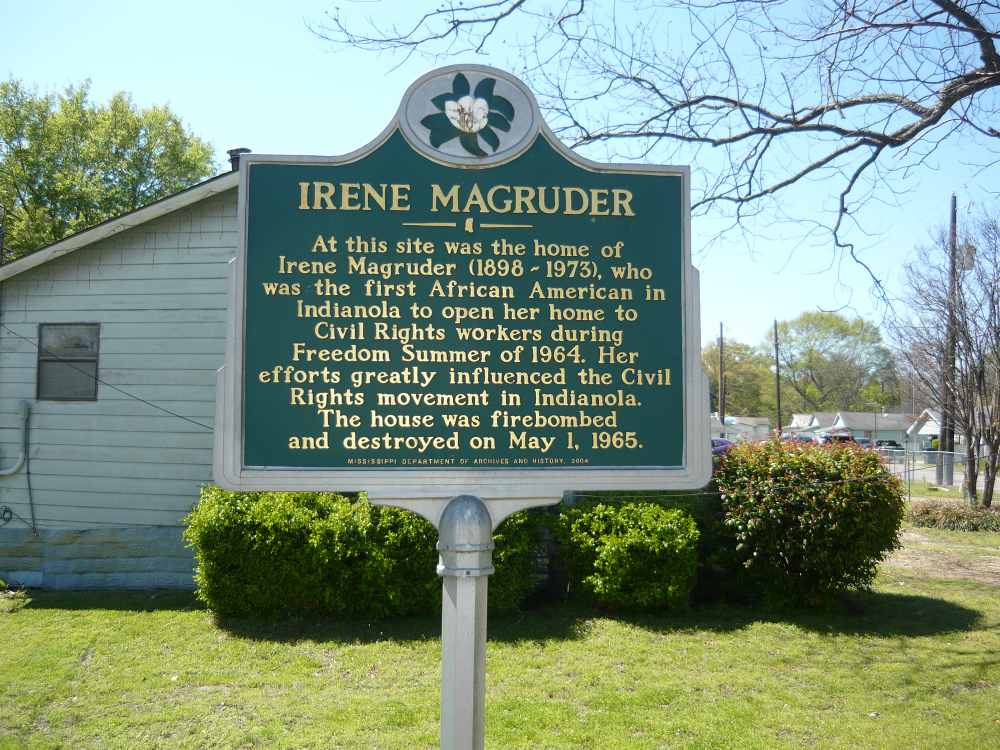

In the summer of 1964, both White and Black college students came to Sunflower County, Mississippi to help Black residents register to vote. They were called Freedom Summer volunteers. I was a very young girl, and several of them stayed with my maternal great aunt, Mrs. Irene Magruder, who was the first African American to open her home to civil rights workers during Freedom Summer in Indianola, Mississippi. Her house was an underground railroad for the civil rights workers. Freedom Summer volunteer, John Harris, writes how the Freedom Summer volunteers were able to enter Indianola:

As I grew older and was able to understand, my mother often shared the stories about the brave local Black people and Freedom Summer volunteers who came down to change Indianola.

After being in Ruleville for maybe 2 weeks in June, it was decided that we had enough workers to broaden our organizing; so it was decided that I would be responsible for going to Indianola since it was the county seat and the location of the courthouse where citizens tried to register to vote.

I drove from Ruleville for a while to Indianola, talking to people in the cafes, homes, and on the street. There was interest in Indianola, in order to build a stable movement. I was eventually directed to see Ms. Irene Magruder. She had room in her house for me and was very willing and brave enough to accept me. At that time (1964), that was a very courageous thing to do. Ms. Magruder said she 'was not afraid.' She would do 'whatever she could to help the movement.'

She was the first Indianola resident to open her home to one of the civil rights workers. This represented a significant breakthrough. Others in Indianola opened their doors and their hearts to the voter registration movement. 210 Byas Street became a symbol and often the center of the movement in Indianola and Sunflower County thanks to the quiet, but strong support of Ms. Magruder and I will never forget her. 1

"At that time (1964), that was a very courageous thing to do.

Ms. Magruder said she ‘was not afraid.’ She would do

‘whatever she could to help the movement.’”

The area where she lived was called, “Bear’s Den,” which was a close-knit working-class community. The Indianola, Mississippi Civil Rights History Driving Tour explains the origin of Bear’s Den:

Shortly after Earnest Benson, brother of Martha Ford came home from WWII, a minstrel show came to Indianola. The show featured a wrestling bear. Earnest took the challenge and wrestled the bear, throwing it the first time. The bear threw Earnest the second time. Later, when Earnest opened up a juke joint next to Hollins Grocery, he named it Bear’s Den. 2

My beloved mother Bernice White, sister Brenda and twin sister Marsha, and I would visit her home and see a diverse group of young adults sleeping on the floor in her den. Because Marsha and I were very young, our parents shielded us from the outside world; therefore, we did not understand what was going on and the significance of their being in Indianola. In my eyes, they were very nice people, and I saw them as playmates. They were different in a good way. The Freedom Summer volunteers stayed in her home until it was firebombed and totally destroyed on May 1, 1965. The homes of Mr. and Mrs. Dudley Wilder and Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Giles, Freedom School and Freedom House were also firebombed on May 1, 1965 in Indianola.

As I grew older and was able to understand, my mother often shared the stories about the brave local Black people and Freedom Summer volunteers who came down to change Indianola. Many were beaten and jailed. Fortunately, no one was killed. She told us the story about Charles Scattergood, a white volunteer, who possessed kindness and Christlike characteristics. He was dragged, bloodied and jailed for protesting Black citizens not being able to use the public library. His mother travelled from the east coast and begged him to return home, but Charles refused and remained in Sunflower County devoted to the civil rights movement. He reputedly kept the shirt the day that he was abused for a long time as a badge of honor.

Freedom Summer volunteers at the 2004 reunion stand outside Drew jail where they had been locked up for trying to get Black people registered to vote.

My mother also shared the story about how she and my father, Dorsey J. White, Jr., registered to vote out of anger in the early 1960s. My mother was a science teacher at Amanda Elzy High School in Greenwood, and she drove four Black female students to a Tri-Hi-Y meeting in her car to Laurel. A white police officer pulled her over for alleged reckless driving. She was quiet and gave him her driver’s license. The policeman used an ugly racial slur in referencing them. That incident was what made her and my father determined to register to vote. My mother received a civil subpoena, and she testified on behalf of the federal government in federal court about voting rights in October 1964.

My family and others often wondered what happened to the volunteers and where they were at that time. A group of Sunflower County, Mississippi civil rights veterans and I came together and organized the civil rights reunions on June 5, 1999, June 3, 2000, August 5-7, 2004, September 11-13, 2008, May 26-28, 2011, June 26-28, 2014 and October 3-4, 2019. I searched for the volunteers online and made many telephone calls and sent numerous emails. The goals of the reunions were to preserve, to commemorate, and to educate the future generations about the civil rights movement in Sunflower County. Several civil rights veterans, who resided and participated in the civil rights movement, returned for the first time since leaving Mississippi in 1964 and 1965 to attend our reunions with their spouses and children. They travelled from Alabama, Massachusetts, California, New Mexico, New York, Connecticut, Minnesota, Missouri, Georgia, Louisiana, Nevada, Tennessee, Washington, DC, Washington state, and even Israel. Sadly, Freedom Summer volunteer, Charles Scattergood, was tragically killed in an automobile accident before our first reunion.

The organizers of the first reunion were people who had been part of the Sunflower County, Mississippi civil rights movement. The reunion included a moving testimony from civil rights veteran, Mrs. Cora Johnson-Stone. It was decided that the reunions would coincide during the B.B. King Homecoming concert in Indianola.

The civil rights veterans’ attendance at the first reunion appeared very promising and efforts were made to reach out to even more veterans. My mother said she was looking forward to seeing volunteers at the second reunion, but she passed away shortly after the first reunion. The second reunion consisted of a reception, B.B. King concert, civil rights bus tour, civil rights memorabilia display, public forum, and dinner. Several civil rights veterans provided testimonies of their experiences in the civil rights movement. The dinner speaker was Sunflower County Freedom Summer Project Director, Charles McLaurin. Back in 2000, I began sharing my vision of interviews with civil rights veterans to show appreciation and posterity. I thought it would be ideal to interview the volunteers, while they were attending our reunions about their experiences in the civil rights movement and changes they have noticed since returning back to Mississippi. Understanding the importance of documenting their stories, I invited the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program to conduct oral history interviews of the civil rights veterans. Working closely with them, these interviews are part of the Mississippi Delta Freedom Project Digital Collection at the University of Florida and can be accessed here.

The goals of the reunions were to preserve, to commemorate, and to educate the future generations about the civil rights movement in Sunflower County.

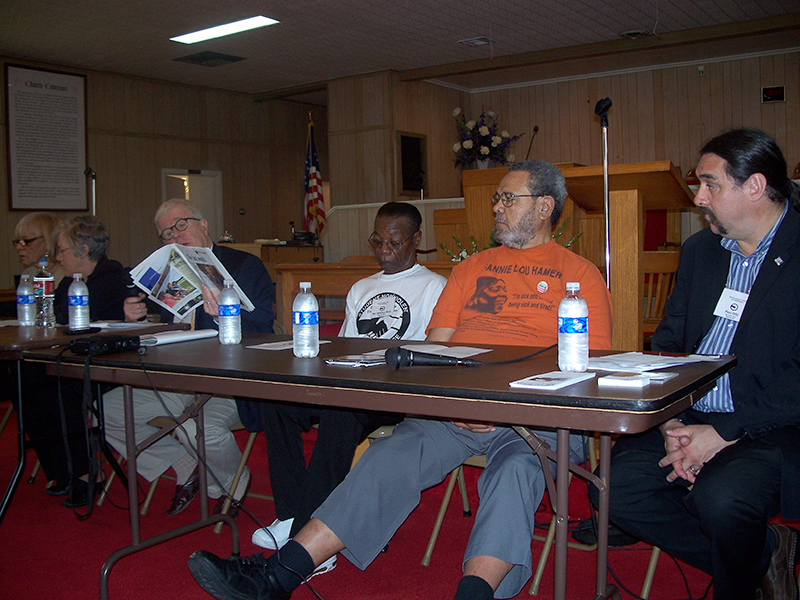

The third civil rights reunion was held in honor of the 40th Anniversary of Freedom Summer in Sunflower County. The reunion included most of the civil rights veterans who previously attended the reunions and a volunteer from Israel. The veterans participated in a reception, civil rights bus tour, panel sessions, viewing of The Intolerable Burden, blues performance by Terry Harmonica Bean and an address from keynote speaker Lawrence Guyot, the first Chairman of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The major event of the reunion was the unveiling of the Giles Penny Savers Store, Freedom School, and Irene Magruder historical markers.

The fourth civil rights reunion took place during the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center grand opening weekend in Indianola. Highlights of the reunion included keynote speaker, Congressman John Lewis; the unveiling of the Indianola, Mississippi Civil Rights History Driving Tour book, which highlights some of the significant individuals and sites during the early years of voter registration in Indianola; and a visit to the Fannie Lou Hamer Memorial Garden; and a play by the Sunflower County Freedom Project students.

The fifth civil rights reunion coincided with the 50th Anniversary of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi. The reunion included a reception, panel discussion, play by the Sunflower County Freedom Project students, guided civil rights tour, and performances by blues musicians, Mickey Rogers and Alphonso Sanders. The dinner speaker was Patricia Thompson, an organizer who helped educate the community about Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer's courage and accomplishments.

The sixth civil rights reunion centered around the 50th Anniversary of Freedom Summer in Sunflower County. The reunion included a reception, tour of the Fannie Lou Hamer Civil Rights Museum and Fannie Lou Hamer Memorial Garden and Museum, dinner and showing of the documentary, Freedom On My Mind, at the B.B. King Museum and a book event at the Henry Seymour Library. The civil rights veterans received a commemorative 50th anniversary souvenir book displaying their photos from 1964-1965 and present reunion photos.

"A lot of the people is still around, glad to see us. It’s just like we became real close, real sisters and brothers, you know what I’m saying."

A scaled back event was held for the seventh civil rights reunion. The civil rights veterans toured the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson. They also had the opportunity to attend the Fannie Lou Hamer 100th Birthday Celebration in Ruleville and the 50th Anniversary of Hawkins v. Town of Shaw.

Today, Sunflower County has a large number of African American office holders. Many believe that this nation would not be what it is today without the contributions and sacrifices of the courageous civil rights veterans who fought for voting rights. At the 2004 civil rights reunion, Freedom Summer volunteer Bright Winn gave an emotional response when asked how he would like to be remembered.

Well, I think it was summed up today by those speakers. We did make a difference. I would ingratiate myself if I said, we came down, we worked, they worked, we sacrificed, they sacrificed (voice breaking up, crying). And, after thirty-five years, we made a difference. (crying) 3

Freedom Summer volunteer Karen Koonan shared her thoughts in a 2004 interview:

No, it’s just what I said yesterday afternoon, it’s just the sense of community here. And also, as a political - someone who’s been a political activist for almost 40 years, the thing I was telling my kids yesterday was, the interesting thing here is that about eighty percent of the community is sympathetic. Not only that, but most of them were active. This wasn’t a movement where there was a vocal minority. This was a movement that really touched the hearts and minds of most of the Black community, so you really felt that sense of being part of everybody and not just being on the fringe. 4

In an August 2009 interview, local civil rights veteran Rev. McKinley Mack, Jr. expressed the sense of family among the civil rights veterans:

Like I was saying, Stacy--Ms. White--and Charles McLaurin, there’s a bunch of people still around. We get together from time to time and we’re having a reunion. All of the civil rights workers that was here at that time, we come back with reunions, and we’re planning another reunion in 2011. We’re working on that now. Then we get back and we go and tour a lot of places that we went to and did work in. A lot of the people is still around, glad to see us. It’s just like we became real close, real sisters and brothers, you know what I’m saying. It’s enjoyable for me, that we can still look at the changes that have been made, that were made and we was part of making that change. So, it really is gratifying to me. It really takes me to the level that I want to be on. 5

These are some of the civil rights veterans who worked hard and long to register Black people to vote in Sunflower County during the tumultuous period of 1964-1965. Their sacrifices provided us with the privileges that we have today. To summarize, the reunions gave the civil rights veterans the opportunity to come together and bond again with the people with whom they lived and worked. During these gatherings, they reflected on the significance of their shared experience in changing the political landscape of America.

Footnotes

- ^ John Harris to Jim Woodrick, September 20, 2003.

- ^ Stacy J. White et al., Indianola, Mississippi Civil Rights History Driving Tour (Jackson: The Hamer Institute at Jackson State University, 2008), 11.

- ^ Bright Winn, interview by Paul Ortiz, August 6, 2004, interview MFP 031, transcript, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Collection, P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida.

- ^ Karen Koonan, Interview by Paul Ortiz, August 6, 2004, Interview MFP 030, transcript, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Collection, P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida.

- ^ McKinley Mack, interview by Khambria Clarke and Amanda Noll, August 22, 2009, interview MFP 052, transcript, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Collection, P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida.