I am 41 years old and I cannot swim. Surprisingly, my inability to swim is directly related to civil rights, or lack of basic civil rights, for Blacks within the state. Growing up in Southwest Mississippi in the 1980s when de facto segregation was still as common as breathing meant that I had limited exposure to public swimming pools. Was there a public swimming pool that Black kids could go to? Sure, but between lack of time, a problem that still plagues working class Black families, lack of energy--my mom was too tired to take us to the pool, and a self-consciousness about my body stemming from too much exposure to popular television and too little self-confidence, I wouldn’t have gone to the one overcrowded pool that Black kids could go to anyway. These issues, coupled with the fact that the two people I knew who drowned, one who was a very close friend, knew how to swim. I came to the conclusion that swimming was highly overrated. Leave swimming to Aquaman and the fish.

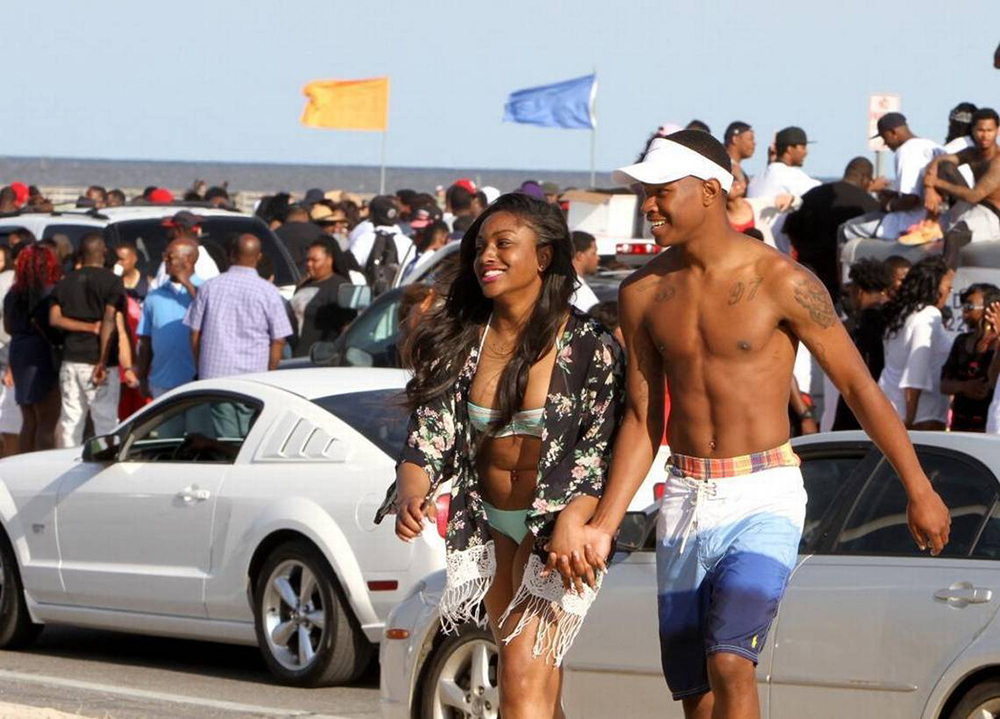

Right: Constance Bailey and her friend, Jamaica Scott, in Biloxi Beach. Photo courtesy of the author.

If for no other reason, Black Spring Break should be celebrated to remind MS residents that only sixty years ago those same beaches were segregated.

This early aversion to public pools gave way to my curiosity about Black people who enjoyed swimming, so as a college student I was so excited to learn, largely through word of mouth, about Black spring break, also called Black Beach. Black Spring Break occurs one of two weekends, sometimes both, that bookend the official spring break of the state schools in MS. 1 Black college students from across the state, and even surrounding states, flock to the Mississippi Gulf Coast in droves. They come to hang out, jet ski, visit local nightclubs, do some shopping, or just to “live their best lives,” as the young people say. Certainly there are families who attend, or maybe even high schoolers who are fortunate to have a drivers’ license and access to a car, but for the most part the expanse of man-made white sand beaches from Gulfport to Biloxi is covered with young Black adults and college students. As unremarkable as all this sounds, young Black people, or any Black people for that matter, could not always go to the beach. For this reason, when I think about the importance of festivals, traditions, and various celebrations that commemorate the legacy of civil rights, Black Spring Break and Black Beach immediately come to mind.

As a former MS Gulf Coast resident, I was always amazed at the lack of welcoming signs for Black Spring Break attendees. Although there was never a formal schedule of events associated with Black Beach that I was aware of, the main activities centered around the Gulfport/Biloxi beaches. When I was in college, my friends and I hit the beach with our makeshift beach towels and rolled up pants legs to wade into the murky Gulf of Mexico waters. Certainly there were many more savvy college students and local residents who hit the beach with all their summertime accoutrement--beach towel, sun hats, beach umbrella, sunscreen (yes there are Black people who use sunscreen), etc. These young people donned the most stylish swimsuits, bikinis, or swimming trunks that their money could buy. Shades of skin that invoked the Diaspora were on display for miles. Think Will Smith’s “Summertime” video but along the beachfront. The juxtaposition of lovely white sand beaches with beautiful Black bodies of all shapes and sizes, really was a sight to behold. By the time the sun set, some groups dispersed to less populated stretches of the beach, some returned to their hotels or homes, and still others got ready to visit one of the local restaurants or nightclubs, but this was in the 90s and early 2000s. These days, there are Facebook and Instagram accounts that announce a diverse array of events including car shows and concerts, but social media was not a thing twenty years ago when I first attended.

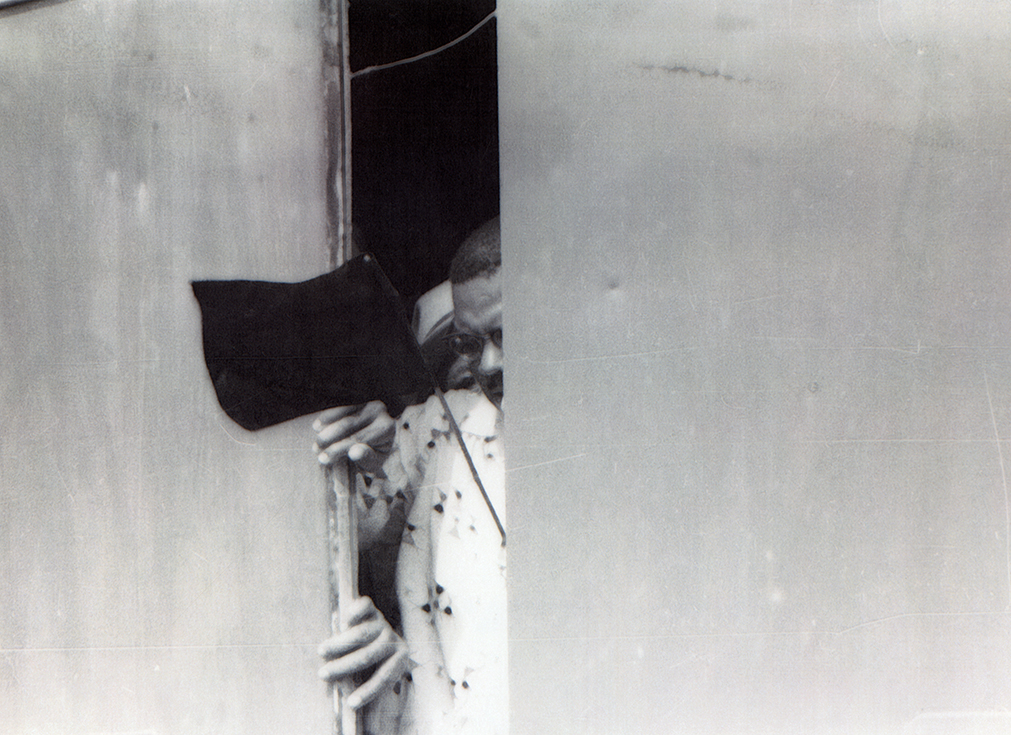

“On the beach just south of the old Biloxi Cemetery sometime between 2:00 and 4:00 p.m., nine of us made our move to start the first wade-in and the first public civil rights demonstration in modern Mississippi history.”

Even as a resident over five years ago, I saw or heard little acknowledgement of the events associated with Black Spring Break, with the notable exceptions being the local Black owned radio station and Black businesses. Now of course I must concede that as a working parent with young children, I was not always privy to what occurred outside my workplace and household. Still, it seemed odd that on my daily commute I would see banners and signage announcing festivals for kites, crawfish, poboys, and any other random culinary treat your heart could desire, but I do not recall seeing a similar beachfront welcome for Black Spring Break. Festivals occur on just about every weekend from April through September in one of the towns along the MS Gulf Coast, and they are part of what gives the region its charm.

If for no other reason, Black Spring Break should be celebrated to remind MS residents that only sixty years ago those same beaches were segregated. There is a highway marker on Biloxi Beach that commemorates the site of the beach wade-ins, but few people outside the city are aware of its existence or its importance, but the historic significance of the Biloxi Beach wade-ins is undeniable.

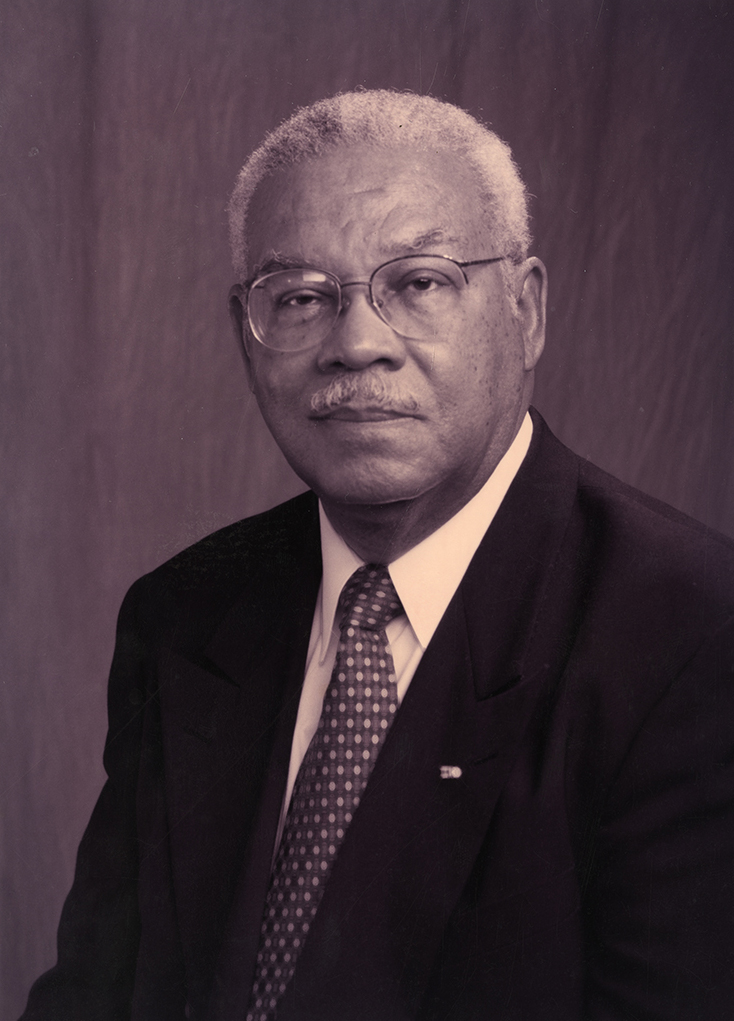

Upon moving to the MS Gulf Coast in 1955, Dr. Gilbert Mason Sr. said that he immediately began to envision desegregated beaches. The beautiful 26-mile expanse of beaches that stretches across Harrison County was one of the reasons the region appealed to him (Mason and Smith 50-53). With this in mind, he spearheaded a campaign to desegregate the public beaches. The first wade-in occurred on May 14, 1959. Mason Sr. writes, "On the beach just south of the old Biloxi Cemetery sometime between 2:00 and 4:00 p.m., nine of us made our move to start the first wade-in and the first public civil rights demonstration in modern Mississippi history" (Mason and Smith 52).

The group was warned by the police to stay away from the beach because it was private property, but of course it was not. The next formal demonstration did not occur until April 17, 1960 because organizers were busy fundraising should they have to take their fight to the Supreme Court. On that afternoon, Dr. Mason was actually the only individual arrested because he was the only one to show up at the Biloxi beach location. Racial animus, intimidation, and violence discouraged other community members from attending, and the Gulfport beach protestors received warnings but were not arrested (Mason and Smith 63).

Inspired by the courage of Dr. Mason’s convictions, many of his patients, church members, and lodge brothers joined him the following week for their nonviolent protest, but when a white mob met them there, they were attacked. The Mississippi Civil Rights Project website notes that, “The Clarion Ledger and Daily News reported this [April 24, 1960] as the bloodiest riot in Mississippi history.” One witness who was present on Bloody Sunday, as it would later be called, while “speaking to local TV station WLOX during the 50th anniversary, even recalled the police encouraging the mob” (Poon). For the witness, Clemon Jimerson, and others who showed up that day, it was about more than just fighting racial injustice for the sake of fighting it. Indeed, it was also a fight “over their right to leisure” (Poon). On June 23, 1963, just a few days after Dr. Mason’s friend, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, was assassinated, he, and other protestors, went to the beach one last time before legal segregation of the Mississippi beaches would be struck down in 1968. Because of the courageous efforts of those MS Gulf Coast residents, “Biloxi’s public beaches have been open to all ever since” (Blakemore).

...by reclaiming a previously segregated space, Black Spring Break

also reaffirms why the beaches were so important

in the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi.

In White Sand, Black Beach: Civil Rights, Public Space, and Miami’s Virginia Key, Gregory Bush poetically describes beaches proclaiming that “as places that change over time, beaches are unique staging grounds and metaphors for the fragility of human existence, enlarging and eroding within a large and sometimes unfathomable universe" (131). The beaches along the MS Gulf Coast are no different. As such, Black Spring Break becomes an important site of recovery, both literally and metaphorically, because it showcases Black joy, and by reclaiming a previously segregated space, Black Spring Break also reaffirms why the beaches were so important in the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi.

Resources

Mason, Gilbert R. and Smith, James Patterson. Beaches, Blood, and Ballots: A Black Doctor's Civil Rights Struggle. Univ Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Links

Blakemore, Erin. “How Civil Rights Wade-Ins Desegregated Southern Beaches.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 21 July 2017, www.history.com/news/how-civil-rights-wade-ins-desegregated-southern-beaches.

Bush, Gregory W. White Sand Black Beach: Civil Rights, Public Space, and Miami's Virginia Key. University Press of Florida, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uark-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4529436. Created from uark-ebooks on 2021-05-12 14:15:15

Poon, Linda. “Remembering the Beaches as Battlegrounds for Civil Rights.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 21 June 2017, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-21/the-bloody-wade-ins-that-brought-equal-rights-to-beaches.

Footnotes

- ^ Due to Covid-19 concerns, the 2021 celebration is scheduled in late August and has been rebranded as the Summer Beach Festival ‘21.