“It’s amazing my little needle could carry me so far!”

When Hystercine Rankin received a National Heritage Fellowship award in 1997, it capped her 56-year journey as a quilter, homemaker, teacher, and artist. As she remembers it, learning to quilt at age twelve signaled the end of childhood and the beginning of responsibility. “[Grandmother and I] quilted in the front room, in front of the fireplace….After we’d come from school and finish our homework, she’d have a lamp on the mantelpiece and we’d quilt into the night. We’d quilt on weekends and rainy days. I’ve been quilting on something ever since…” She learned her craft in the most traditional of ways, in and among her family and the community near Blue Hill in Southwest Mississippi. Just as there were always mouths to be fed, there were always beds to be covered. “We did a lot of quilting....Wasn’t no buying and selling quilts in those days. You just gave them away. Poor folks didn’t have nothing. We weren’t rich, but we had our land and a big garden, so we didn’t go hungry. Everybody was poor then.” 1

Her early quilts belong to a tradition of Southern Black vernacular quilting practiced by many other Southwest Mississippi quilters.

Hystercine (pronounced Hur’-tuh-seen by all who knew her) was the third of eight children born to Denver Gray and his wife, Laula. Her family tree’s roots go deep in Mississippi’s troubled past and help to explain her extraordinary self-reliance, industriousness, and devotion to family. Her great-great-grandfather was an enslaved Black man conscripted by the Confederate Army “to dig ditches, carry water, and gather wood.” He and two sons were killed during the siege of Vicksburg in 1863. His youngest son, Joe January, who was Hystercine’s great-grandfather, survived and prospered by dint of hard work, earning enough to buy 100 acres of bottomland and build a substantial house. In 1878, Joe married Elvira Segrest, an educated woman who taught him to read and write. 2

Prosperity, however, did not mean security for a Black man and his family. One local white man raped his wife and another raped his daughter Alice. “Daddy Joe” raised as his own the two daughters born from these violent attacks, but it pained him that he couldn’t defend his family. Hystercine recalled being told, “[He] sat in the hallway of the big house he’d built, with a shotgun on his lap, and just cried like a little baby… He had his family to look after, and if he went for that white man, they would have killed Daddy Joe, probably burned his place and taken the land. That’s just the way it was in those times.”

Alice’s child, Laula, red-haired and freckle-faced like her white father, married Denver Gray on Christmas Day in 1925 at the age of nineteen. Their third daughter, Hystercine, was born in 1929. She took pride in the reputation of her father as a man “who didn’t cow down to white folks, and… if he saw a white man bothering anybody colored, he’d stop him. They didn’t like that.” Violent tragedy struck in 1939 when Hystercine’s father was shot and killed by a white man in the road near their house. She was not yet ten years old. The day her father was buried, her grandmother Alice loaded up Laula and her children in a wagon and took them back to live with her on Joe January’s farm. It was there that twelve-year-old Hystercine began to learn about quilting.

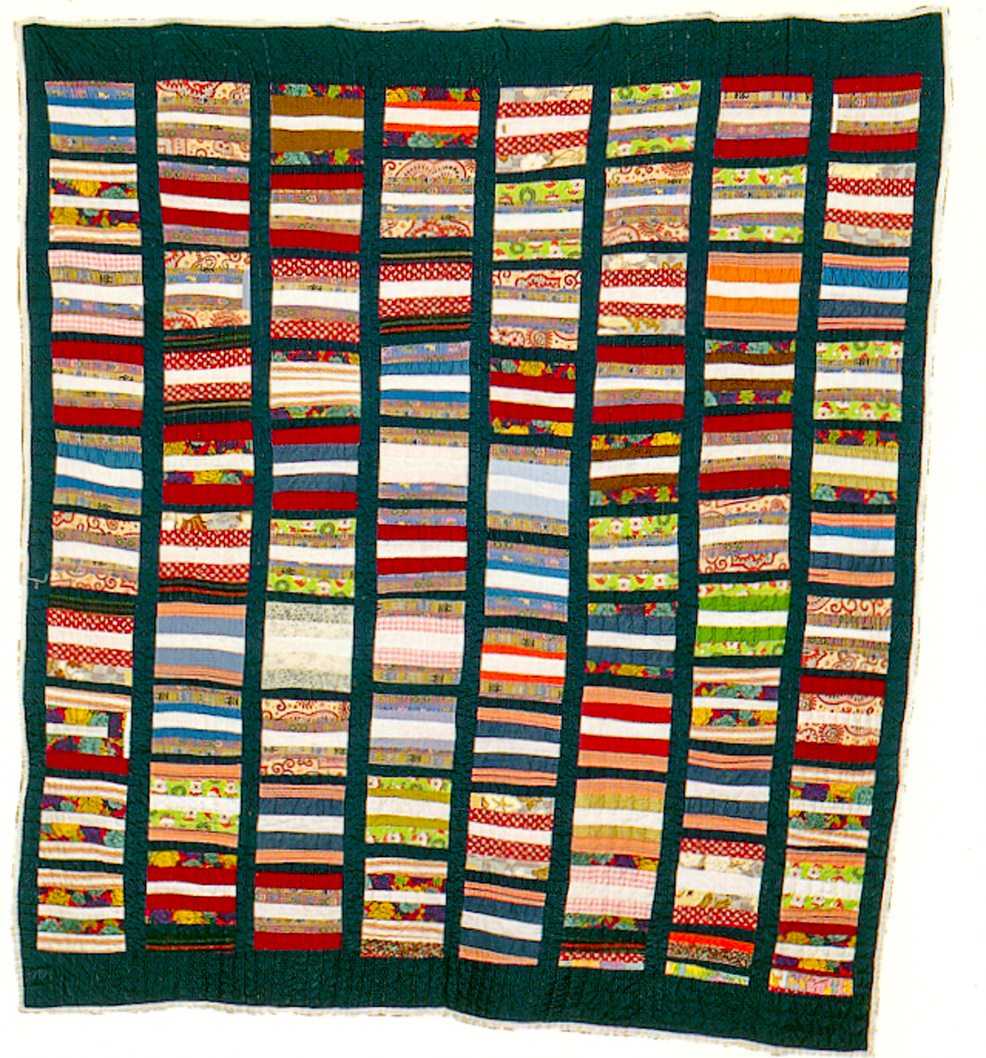

Her early quilts belong to a tradition of Southern Black vernacular quilting practiced by many other Southwest Mississippi quilters. They were utilitarian bed covers, made from pieces and strings of old cloth, sewn into strips, then joined together to make the right size for a bed. 3 For years she designed quilts using whatever materials were available, including the ends cut off the pants she shortened for her sons. She called the pattern “Britcher Leg.”

Above (main image): Hystercine Gray Rankin (1929-2010) receiving the National Heritage Fellowship award in 1997 from First Lady Hillary Clinton and Jane Alexander, head of the National Endowment for the Arts. Her response to the honor: “It’s amazing my little needle could carry me so far!”

Photo by Patricia Crosby.

Right: This Britcher Leg pattern obeys one of the community’s unwritten rules, “It isn’t a quilt if it doesn’t have a little bit of red in it.” It also demonstrates how design principles can be handed down from one culture to another. The long vertical strips alternate the direction of the small strings and where they change direction they often change the width of the string, just as the alternation of fabrics creates a wavy outline in long narrow strips of woven Kente cloth.

Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

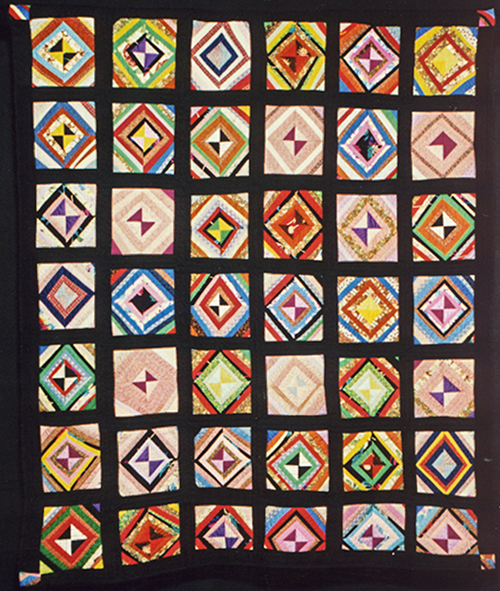

Another quilting style Hystercine’s grandmother taught her was a little fancier. She was told that during slavery times her great-grandmother would bring strings home, cut small squares out of old material and cover the squares with diagonally placed strings. Then, she would join four squares to make a block with the little triangles at the center and outer corners. 4 Hystercine’s version used many different colored strings as she built her own String Quilt.

Each block of this String Quilt contains four squares of muslin covered with brightly colored strips sewn diagonally. When they are joined together they form a block resembling a square on point. In this quilt Mrs. Rankin created six vertical columns of seven blocks and sewed them together to form the final quilt. Each block is separated from the others by a lattice of black strips to suggest the panes of stained-glass windows.

Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

In 1945, when she was 16 years old, Hystercine married Ezekiel Rankin and became Mrs. Hystercine Gray Rankin. Ezekiel was an army veteran, just returned from the war and eager to demand his rights as a citizen. He registered to vote and purchased land where he could farm and raise a family. Soon the Rankins took in her five younger brothers and then there were seven children of their own, meaning lots of new beds to be covered with home made quilts.

In the 1970s, Mrs. Rankin began to experiment with patterns that came to her in dreams. One night she went to bed thinking about all the strings she had and how she could use them. By morning she had dreamed a pattern made of multiple blocks of five contrasting color strings sewn horizontally with a white string always in the center. Some might call it a Jacob’s Ladder, but for Mrs. Rankin it was a Rainbow.

For quilters who love to repeat the same pattern in every block, this Rainbow quilt is a serious challenge. Although a white string is at the center of each block it is flanked top and bottom by a kaleidoscope of different colored strings which do not repeat. And because the width of the strips varies, when they are sewn into vertical columns and the columns are joined together, nothing lines up.

Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the collection of David and Patricia Crosby.

Another significant creation came from a vision she had one afternoon when she looked up from her quilting frame to see the sun setting a brilliant orange in the blue spring sky, with shafts of sunlight piercing the clouds. From that vision she designed a quilt with a large whole-cloth orange square in the center, surrounded by strips with squares at the corners. Two strips, built of black and blue right triangles, represented the sun’s rays breaking through the clouds. Mrs. Rankin named it Sunburst.

This Sunburst pattern became one of Mrs. Rankin’s favorites, which she varied through the years. The large central block is reminiscent of medallion quilts common in Amish tradition, but she reimagines it in terms of her everyday experience of earth and sky in Mississippi.

Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

Those strips of triangles also got her thinking of a darker reality of Black life in Mississippi: the incarceration of so many young men. Using this as inspiration, Mrs. Rankin created a variant of the Sunburst quilt pattern, but in place of the whole-cloth central square she created a nine by ten matrix of four-patch squares, representing prisoners, and surrounded them with a strip of triangles representing prison guards. Around them she filled the quilt with more four-patches and finished it with an outer strip of triangles. The glorious Sunburst had become a sinister Parchman Prison.

Based loosely on her Sunburst pattern, this Parchman Prison quilt reverses the energy. Whereas the sun bursts outward through the surrounding strips, the concentric double walls here force the fragmented population of squares into the center. Even the squares outside the inner prison are surrounded by force as well.

Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

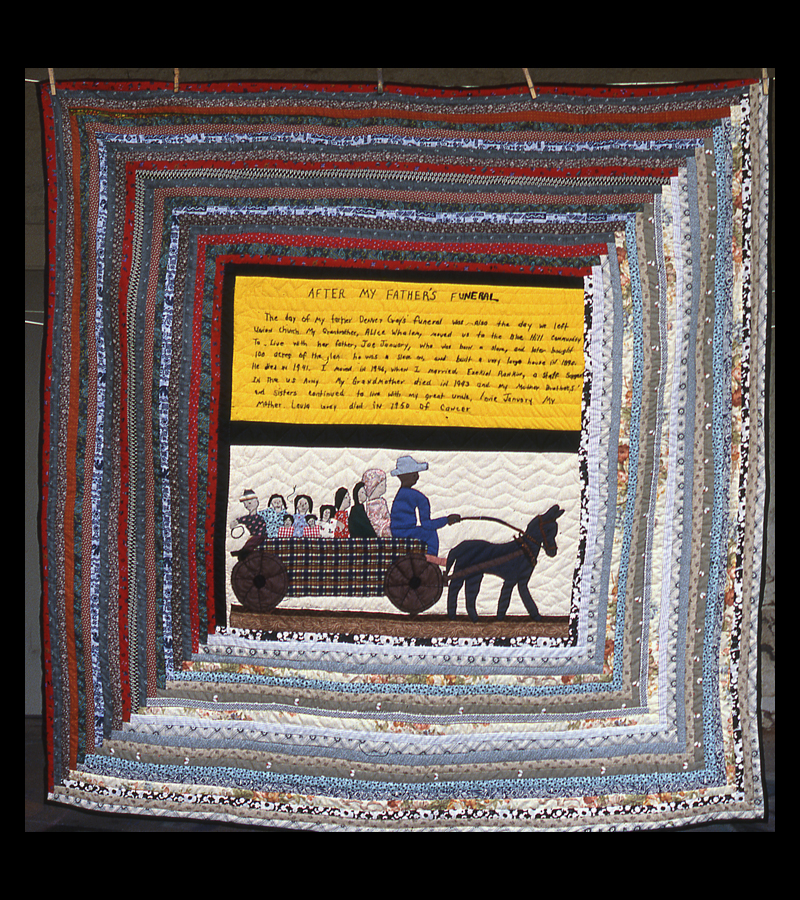

When the pieces and strings in a quilt become more than just abstract design elements and begin to represent natural or man-made events, they take on a story-telling function. They refer to something that happened–either to the designer personally (Sunburst) or to the society in which she lives and works (Parchman Prison). Roland Freeman–photographer, quilt historian, and collector–noticed this movement toward story-telling in Mrs. Rankin’s work and suggested that she tell the story of her father’s death in an appliquéd quilt. Mrs. Rankin hesitated to make such a private grief public, but eventually decided it was time. The resulting two quilts, “Memories of My Father’s Death” and “After My Father’s Funeral” are among her most forceful social statements.

Moving from iconography to storytelling required skills new for Mrs. Rankin: converting a scene held in memory as a four-dimensional experience to the two dimensions of a quilt, and the art of appliqué, layering cloth on cloth. She used her familiarity with the sunburst design to center a visual image and added words above and below to recite a narrative and provide context. Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

In her second treatment of these traumatic memories Mrs. Rankin combined elements of two traditional patterns, the medallion and the log cabin. Parts of the narrative are combined in a single central square, much like an illustrated book, but the frame is no longer enclosing the story within walls. The cart is taking the family into the lighter strips and away from the darker, and the stair-step effect of the log cabin design ensures that no string fully imprisons the lives of the people. Photo by Patricia Crosby; the quilt is in the permanent collection of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

According to Southern folklorist Deborah Boykin, these quilts document “a deeply personal trauma, her father’s murder by a white man… Creating the quilt was a healing process.” In 1995 Mrs. Rankin told an interviewer, ‘When I did this quilt of my father, that was a joy to put it on a quilt. It just relaxed me.’” 5 It also opened a floodgate of story quilts based on her own life and that of her community.

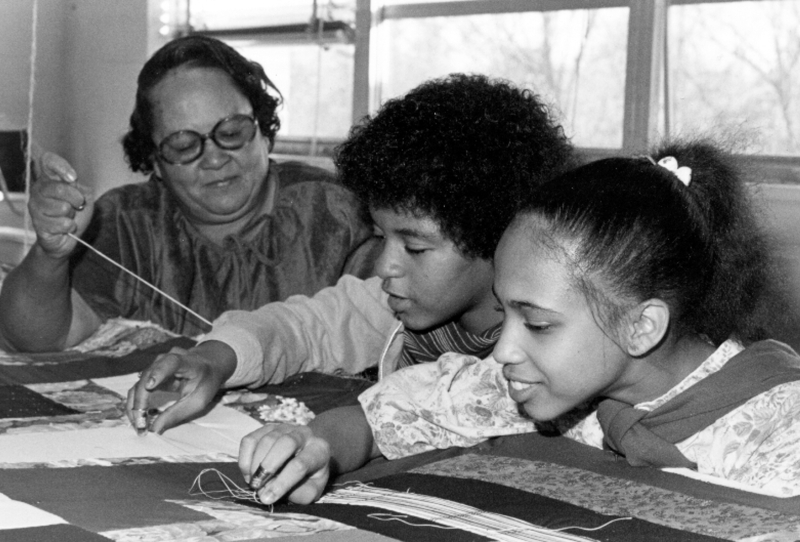

Mrs. Rankin first realized that others might consider her an artist in 1981 when she was 52 years old. Mississippi Cultural Crossroads (MCC), a fledgling local arts agency in Port Gibson where her daughter went to school, invited her to participate as a folk artist in an Artist Residency in the Schools program funded by the Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC). There for two weeks she taught middle school students to piece and quilt and participated in an exhibition of local quilts arranged by MCC in Port Gibson’s National Guard Armory. In the years that followed her residency it became clear that Mrs. Rankin had both extraordinary design skills and was committed to her craft in a special way. Concluding that the local community had much to learn from her, MCC began collecting and photographing her quilts so she could apply (successfully) to MAC for a Folk Arts Apprenticeship grant which paid her $2,000 to teach a group of six apprentices. With the grant came official recognition of her as a Master Artist in the apprenticeship program.

Mrs. Rankin demonstrates her stitching technique for students Yolanda Brown and Valorie Spencer as a folk-artist in residence at Addison Jr. High in Port Gibson in 1980. Photo by Patricia Crosby

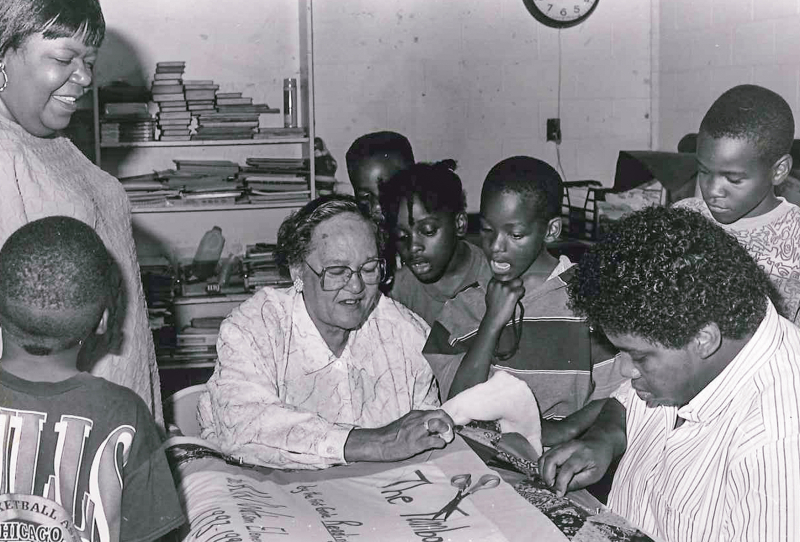

This group of boys flocked to Mrs. Rankin perhaps because she believed that every person could benefit from the art of quilting. She often sought out the students who were considered troublesome and trusted that they could be reached by kindness and love. Looking on is teacher’s aide Gwen Aikerson Brooks and sitting at the frame is volunteer Esther Rogers. Photo by Patricia Crosby

In 1988, Mrs. Rankin joined MCC as a part time quilting teacher and helped to found Crossroads Quilters, a loosely organized cooperative of women, most of them African Americans, who display and sell their one-of-a-kind handmade quilts through MCC. One of their projects is an annual quilt contest and show titled “Pieces and Strings,” which offers cash prizes and provides a venue for selling competing quilts. From the beginning both black and white quilters were encouraged to enter, and the first judges–Roland Freeman and Patty Carr Black, director of Mississippi’s Old Capitol Museum–decided to create many categories for judging, including styles like traditional patterns, improvisations on traditional patterns, bits and pieces, story quilts, and so on. Over its first 18 years, Pieces and Strings attracted 939 quilt entries from many places around the state. Over the first ten years, Mrs. Rankin won 13 first-place awards in several different categories. Her recognition was amplified across the state when the Mississippi Museum of Art agreed to hang each year’s winning entries as a summer exhibit in their own galleries.

Crossroads Quilters, which Mrs. Rankin helped found in 1988.

As her fame grew Mrs. Rankin began to earn prizes of increasing monetary value and prestige. In 1990, she won the Susan B. Herron Award and Art Fellowship, which included a prize of $5,000. In 1993, she received $5,000 when she won the Southern Arts Federation/NEA Regional Visual Arts Fellowship. A few years later in 1997, she was the recipient of the NEA National Heritage Fellowship, which included an award of $10,000. Her quilts are also in many private collections around the nation and in the permanent collections of the Mississippi Museum of Art and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Her work has been featured in videos created by Craft in America, Egg: the Art Show, CBS, and NBC.

From a humble beginning of learning stitches with her grandmother before the fireplace, Mrs. Rankin continued to work with people of all races and ages to introduce them to the joy of quilting. She promoted creativity until her death in 2010. She once told a group of beginners, “You can create such beautiful patterns without looking at nobody’s work. This is yours. You can give the quilt to someone, but the joy you get from starting from nothing and making something beautiful is yours.” 6 And perhaps this is the key to Mrs. Rankin’s success—the recognition that great beauty and meaning can be found in the act of making something useful and sharing it with others.

Mrs. Rankin poses before one of her Sunburst Quilts in an exhibition at Mississippi Cultural Crossroads.

Photo by Patricia Crosby

Video courtesy of CRAFT IN AMERICA (www.craftinamerica.org)

Video courtesy of CRAFT IN AMERICA (www.craftinamerica.org)

To learn more about the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) or to nominate a Mississippi traditional artist for a NEA National Heritage Fellowship, please visit their website.

Footnotes

- ^ Quotes are from Mrs. Rankin’s interview with Roland Freeman, A Communion of the Spirits, 94-95. (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1996), 94-95.

- ^ Biographical details come from these sources: Hystercine Rankin, interviewed by Octavis Davis, I Ain’t Lying, vol. 2 (Port Gibson, MS: Mississippi Cultural Crossroads, 1982), 64; Ann Brown, “Hystercine Gray Rankin: Quilter Extraordinaire,” The Fayette Chronicle (July 18, 1989); Roland Freeman, A Communion of the Spirits, 85, 91-99

- ^ For a discussion of one tradition in Southern Black vernacular quilting, see David Crosby, Quilts and Quilting in Claiborne County: Tradition and Change in a Rural Southern County (Port Gibson: Mississippi Cultural Crossroads, 1999).

- ^ For a fuller explanation with illustrations of how to create a string quilt, see Crosby, Quilts and Quilting in Claiborne County, 20-22.

- ^ Deborah Boykin, “Hystercine Rankin,” an essay accompanying “Hystercine Rankin,” a solo exhibit at The Museum of Arts and Sciences, (Macon, GA., January 17-February 23,1997)

- ^ Hystercine Rankin, quoted by Boykin