“I couldn’t have did them much good just marching and marching only.

I could do better by helping them raise money to get them

out of jail, and I did a lot of that.”

– B. B. King on his alternative form of protest during the civil rights movement 1

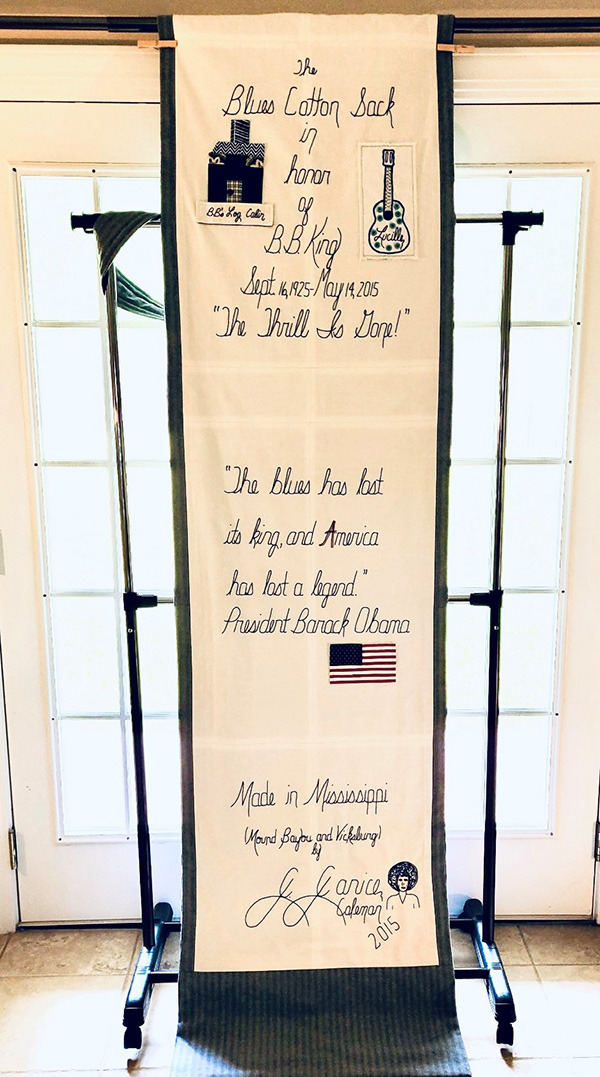

A professor at a college in Los Angeles who had invited B. B. King to perform asked the blues singer, “Did you study the Blues? Why the Blues?” 2 King admitted that he had not finished high school, adding, “I think I’ve had the blues all my life. [On September 16, 1925], I was born in poverty and hunger on a Mississippi plantation.” A “Wednesday’s child,” 3 King stated further that his mother died when he was nine, and afterward he became a farmhand who was left to fend for himself, asking, “Does it have to be like this?” 4 Through makeshift means, King later learned to play the blues, naturally progressing to professional status. When King died, on May 14, 2015, I began my tribute to him as a fellow Mississippi Delta artisan by making the B. B. King Blues Cotton Sack that tells the story of his rise from rags to riches. Using various scraps of discarded fabrics, which some called rags, I stitched quilt patterns into an eleven-foot bag to capture the story of King’s journey from the humblest of beginnings to places of prestige and privilege. An integral part of this patch-worked narrative is the role that King played in the civil rights movement.

Using various scraps of discarded fabrics, which some called rags, I stitched quilt patterns into an eleven-foot bag to capture the story of King’s journey from the humblest of beginnings to places of prestige and privilege.

King was a self-proclaimed dues-paying member of the movement. These are the dues that he sings about in “Why I Sing the Blues”:

When I first got the blues

They brought me over on a ship

Men were standing over me

And a lot more with a whip

And everybody wanna know

Why I sing the blues

Well, I’ve been around a long time

Mm, I’ve really paid my dues.

King paid his dues, both literally and figuratively, as when he and his band members were travelling across the South by bus and stopping at service stations where they were not allowed to use the restroom. In these instances, King would pull into a service station and inform the owner that he intended to fill his gas tank, a 130-gallon hold. In the meantime, surveying his surroundings, King would note that a station would sometimes have two restrooms, one for white men and one for white women, but not a “pot to piss in” 5 for the weary bluesman. King says that when an attendant had put about a gallon of gas in his bus, he would ask if he could use the restroom. A customary response from the owner would be, “Sorry! You know, it’s out of order,” and King would then say to the attendant, “Don’t put no mo’ gas in there.” 6 This was, King says, “back in the days when segregation was in full swing.” By this nonviolent action, King was protesting racial discrimination in the tradition of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and practicing what Medgar Evers, another civil rights leader, was preaching: “Don’t Buy Gas Where You Can’t Use the Restroom.” 7

Despite its peaceful nature, King’s activism did not go unnoticed. In the mid-seventies, a writer noted that King’s lyrics were becoming more radical than they had been in past years, that they seemed to have evolved from narratives about love affairs gone wrong to calls for freedom, justice, and equality for Black people. When he questioned the bluesman about this rhetorical shift, King admitted that the language of his blues was sometimes ambiguous. “You see, years ago, you could not say or sing what you wanted to say,” he said, “and the Blues served as a vehicle to relay a message, and that message in fact was social, and it was about conditions, and very often when I [sang] about a woman, I, in reality, would be singing about a social situation.” 8 The lyrics of King’s “How Blue Can You Get?” provide an example:

I’ve been downhearted, baby

Ever since the day we met

I said I’ve been downhearted baby

Ever since the day we met

Our love is nothing but the blues, woman

Baby, how blue can you get?

The “woman” here, dressed in coded language, is undoubtedly America.

“You see, years ago, you could not say or sing what you wanted to say...and the Blues served as a vehicle to relay a message, and that message in fact was social, and it was about conditions, and very often when I [sang] about a woman, I...would be singing about a social situation.”

Years later, King was convinced that peaceful protests, his and others, were making a difference in the struggle for Black civil rights, and they inspired him to speak more unequivocally against civil wrongs. On June 2, 1984, he attended the eleventh annual Medgar Wiley Evers Homecoming which was held in Jackson, Mississippi, to name a street in honor of the slain civil rights leader. When asked for comments, King cast aside the idea of coded messaging, choosing instead to openly credit Evers as a positive changemaker by noting the stark difference between the Mississippi of the present that Evers had helped to shape and the one of racial segregation and strife that he had known for most of his life. “The changes now in Mississippi are as different as night and day,” King said. “It’s good to be born [in Mississippi] now. Black people have a lot more than they used to. They may not have as much as whites, but they have a better opportunity of getting it.” 9

If he did not know it before, King knew that he had gotten it on February 15, 2005. On that day, both King and I had been invited to the Capitol in Jackson to receive awards—but for different reasons, of course. King was there because Governor Haley R. Barbour had declared it B. B. King Day for the entire state of Mississippi, and I, deemed an outstanding faculty member at Alcorn State University, was there to receive an award for excellence in teaching from the Mississippi Legislature. Nevertheless, as fate had arranged it, King and I were in the same place at the same time, and what King said of the day, with tears of joy streaming down his face, was true for both of us: “This has been the most beautiful day of my life.” 10

Another truth regarding King came in an observation that a writer made shortly before the B. B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center opened in Indianola in September of 2008: “We use B. B. King, his life and his successes, as an example,” she stated. “He was a tractor driver, a sharecropper, and he has been to the courts of kings and popes. He’s traveled around the world and received every kind of award you can imagine. He came from the same place that we all live in, yet he was able to accomplish so much.” 11 That sameness of place, the Mississippi Delta, is the thing that inspired me to prepare to pay tribute to King through the medium of a cotton sack the moment I heard that he had died. The sack features, on its top, three quilt patterns that relate the story of King’s life: the pinwheel, the log cabin, and the nine-patch. On its back or underside, the sack displays narratives and graphics about the King and me.

The Pinwheel Pattern

The pinwheel is a traditional American quilt pattern. It is usually composed of eight triangles in two—or sometimes three—contrasting colors or designs which are arranged in a square that mimics the rotating pinwheel. On this sack, each of the three pinwheels appears as a square on the left-hand side. Following the traditional design of the pinwheel pattern, it is the most conspicuous pattern on this sack because each is composed of the dynamic chevron print and solid blues which make the pattern easy to recognize. In the center of each pinwheel is an orange button, which matches the color of the flame in the log cabin and marks the point from which the wheel turns. The pinwheel represents both faces of bluesman King, the times when he was letting the good times roll as well as the times when the thrill was gone. During both of these times, King, like the pinwheel, kept on turning.

The Log Cabin Pattern

The log cabin is another traditional American quilt pattern. It usually features a small, center square block in red, yellow, or orange which signifies the glowing fire of the hearth within the cabin. Surrounding the blaze, in the traditional pattern, are L-shaped strips of fabric which represent the logs. On this sack the three log cabins are the patterns to the right of or alongside the pinwheels. They are variations of the traditional log cabin design in that the hearths, represented in orange, are surrounded by logs that are more inconsistently placed than the ones in the traditional pattern. The wayward placement of the logs allows the pattern to reflect the lack of precision and refinement in the structure of these rural dwelling places that, in the Delta, were built mostly for sharecroppers and their families. The shanty-styled log cabin was a humble abode, and on a plantation such as that of Berclair where the king of the blues was born, the cabin would have been akin to the biblical manger—lowly but still the only place for a poor boy like King. The design of the cabin itself may have mirrored that of a patchwork quilt, for it may have been pieced together from used wood, tin, nails, and other recycled materials.

The Nine-Patch Pattern

The nine-patch is also a traditional quilt pattern. It is usually composed of two alternating colors that are grouped by threes to make up three rows. On this sack, it is the dominant pattern, but it often appears as a variation of the traditional design because a single nine-patch block is sometimes composed of as many as seven or eight different patches to reflect the unregimented lifestyle of the traveling bluesman who was always on the move, going “from Spain to Tokyo, from Africa to Ohio,” as King says in “You Never Make Your Move Too Soon.” By using the nine-patch pattern as a template, one could easily chart the ninety years of King’s life decade by decade, noting a major event in each of the ten years and recording it within one of the nine rectangles of each block. Here, there is plenty of room to tell and expand the story of King’s life, for this sack has six rows of quadrupled nine patches, totaling twenty-four rows.

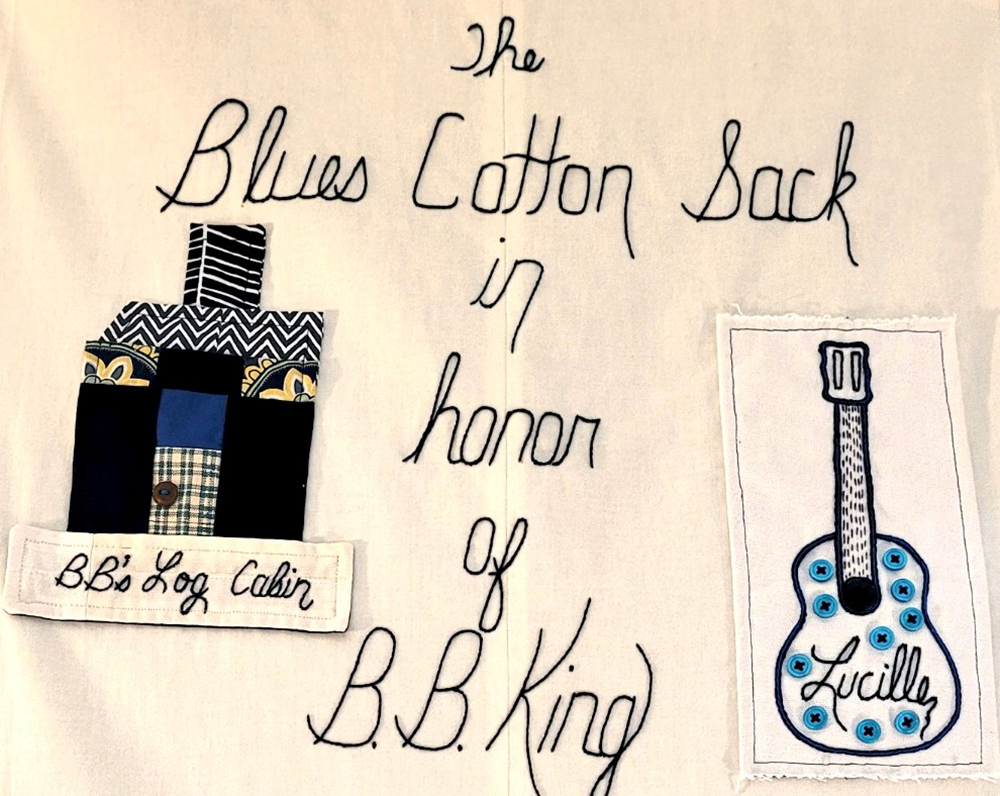

Two panels of information on the sack’s back continue the biography of King, and a third one provides information about me as the sack’s maker. The first panel names the bag as a cotton sack in honor of King’s life and legacy. It also cites King’s birth and death dates, and, beneath these, the title of King’s signature song, “The Thrill Is Gone.” This panel also contains two graphics. Reminiscent of King’s boyhood homes, one is a log cabin that is constructed from some of the same blue fabrics that are on the topside of the sack. The other graphic is King’s iconic guitar, Lucille, stitched in navy blue and lighting up the sack with bedazzling aqua blue buttons.

The second panel reflects President Barack Obama’s farewell tribute to King, in whom Mr. Obama might have seen a little of himself—as someone who entered the world humbly but had the audacity to hope for a better future than the circumstances of his birth and early childhood would suggest. On February 21, 2012, President Obama invited King and other blues musicians to the White House to perform at a “Red, White, and Blues” concert, for he understood the blues as the nucleus of a great many musical traditions in America as well as the conveyor of feelings within humanity that runs the gamut from agony, angst, and tragedy to good and glorious times. Reflecting on King’s choice genre, Mr. Obama said:

This is music with humble beginnings—roots in slavery and segregation, a society that rarely treated Black Americans with the dignity and respect that they deserved. The blues bore witness to these hard times. And like so many of the men and women who sang them, the blues refused to be limited by the circumstances of their birth. The music migrated north—from the Mississippi Delta to Memphis to my hometown of Chicago. It helped lay the foundation for rock and roll and R & B and hip-hop. It inspired artists and audiences around the world . . . and the blues continues to draw a crowd because this music speaks to something universal. No one goes through life without both joy and pain, triumph and sorrow. The blues gets all of that, sometimes with just one lyric or one note. 12

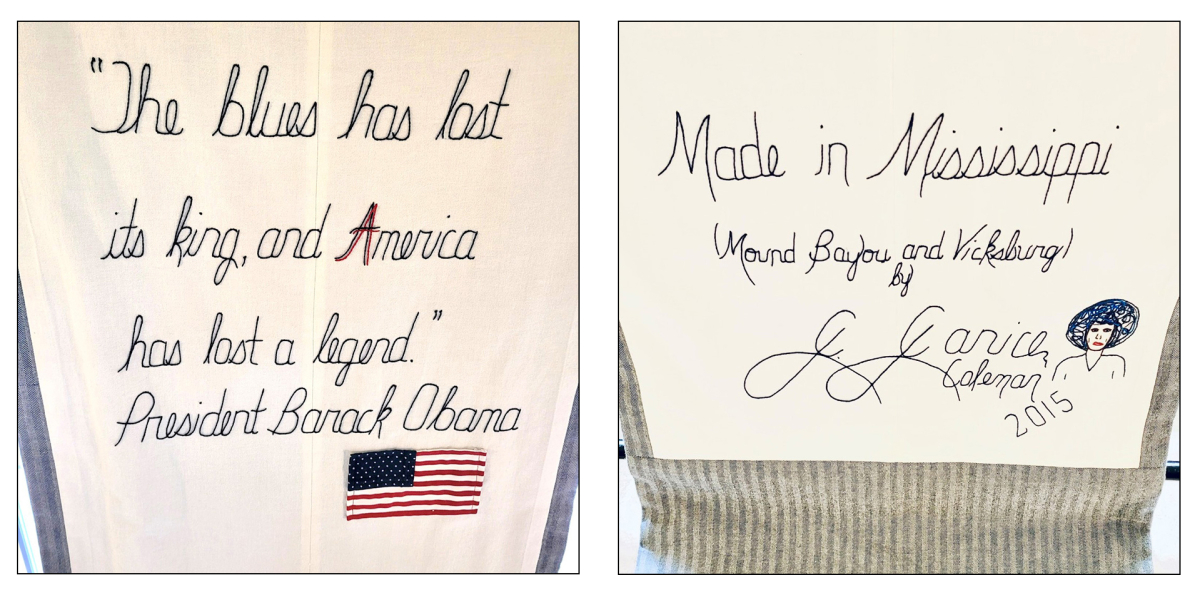

On the day of King’s death, the President, acting as the nation’s “Comforter-in Chief,” observed, “The blues has lost its king, and American has lost a legend.” 13 This quote appears on the sack, followed by the speaker’s title and name: President Barack Obama. Below the President’s name is an image of the American flag, that symbol of freedom, justice, and equality that accounted for both Obama’s and King’s presence in the White House, even for such an event as a blues concert.

The third and final panel on the back of the sack relates the production information. It indicates that the bag was made in Mississippi, specifically Vicksburg, where I now live, and Mound Bayou, my birthplace. It also points to me as the maker of the sack, not just by my signature, but also by my self-portrait in which I am stylin’ and profilin’ in a blues afro. Finally, below my signature and portrait is the year 2015, the one in which I made the sack and, more importantly, the one in which King would have turned ninety had he survived for just four months more.

And yet, King does survive. Six years after his death, he still reigns, as he was generally known, as “the undisputed King of the blues.” He lives on through his legacy of “confessin’ the blues,” his description of his lifetime of work. On the day after King’s death, Lenny Kratviz, whose multi-faceted musical style includes rhythm and blues, recognized the persistent presence of King by addressing the bluesman directly in a tweet, acknowledging the power, the sole power, of King’s words: “BB, anyone could play a thousand notes and never say what you said in one.” 14 King’s legacy, however, extends beyond the world of music. It includes the story of how he rose from poverty in the Mississippi Delta to occupy space in brave new worlds all around the globe. It also includes the story of how he fought to make the world better by playing an active role in the civil rights movement. No, he wasn’t a marcher, but he was, nevertheless, one of the movement’s movers and shakers. Somewhere, in either concrete or abstract form, I have stitched all the stories of King’s life into the making of the B. B. King Blues Cotton Sack, and one can find them in the reflections of the pinwheel, the log cabin, and the nine-patch as well as in the expansion of the narratives on the backside of the sack.

That sameness of place, the Mississippi Delta, is the thing that inspired me to prepare to pay tribute to King through the medium of a cotton sack the moment I heard that he had died.

Resources

“Monday’s Child.” Big Book of Nursery Rhymes and Fairy Tales. Illustrated by Eric Kincaid. New Margaret, England. Brimax, 1989.

Pettus, Emily Wagster. “Most Beautiful Day of My Life, Says B. B. King.” The Bolivar Commercial, 16 Feb. 2005.

Rundles, James. “Up and Down Farish Street.” Jackson Advocate. March 27-April 2, 2008.

Sewell, George Alexander. Mississippi Black History Makers. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, l977.

Stringer, Debbie. “New Museum Honors Indianola’s Famous Son.” Today in Mississippi, Sept. 2008.

Projects

“Artists and the Movement.” Wall panel. B. B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center. Indianola, Mississippi. n.d.

Life on the Road. Produced and directed by Jim Dollarhide, interviewees B. B. King and others, narrated by Dennis Haybert. B. B. King Museum, 2009.

Links

Flores, Reena. “Obama on B. B. King’s Death.” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/obama-on-bb-kings-death-blues-lost-king-america-lost-legend/. 15 May 2015.

“NAACP History: Medgar Evers.” https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/medgar-evers. Accessed 3 March 2021.

Footnotes

- ^ The quote above is from the “Artists and the Movement” wall panel at the King Museum in Indianola, Mississippi. n. d.

- ^ George Alexander Sewell. Mississippi Black History Makers. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1977, 202.

- ^ “Wednesday’s child” is a description from “Monday’s Child,” a Mother Goose nursery rhyme. The full line reads, “Wednesday’s child is full of woe.” King was born on Wednesday, September 16, 1925

- ^ Sewell, Mississippi Black, 202.

- ^ “Pot to piss in.” This phrase is from a popular saying that identifies one as a have-not by stating a basic necessity that one lacks. The complete expression is that one doesn’t have “a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of.”

- ^ Life on the Road. Produced and directed by Jim Dollarhide, interviewees B. B. King and others, narrated by Dennis Haybert. B. B. King Museum, 2009.

- ^ “NAACP History: Medgar Evers.” https://www.naacp-history-medgar-evers/. Accessed 3 March 2021.

- ^ Sewell, Mississippi Black, 203.

- ^ James Rundles. “Up and Down Farish Street.” Jackson Advocate. March 27-April 2, 2008, 13B.

- ^ Emily Wagster Pettus. “Most Beautiful Day of My Life, Says B. B. King,” The Bolivar Commercial, 16 Feb. 2005, 6.

- ^ Debbie Stringer, “New Museum Honors Indianola’s Famous Son,” Today in Mississippi, Sept. 2008, 15.

- ^ “Remarks by the President at ‘In Performance at the White House’ Blues Event.” https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. 12 February 2012.

- ^ Reena Flores. “Obama on B. B. King’s Death.” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/obama-on-bb-kings-death-blues-lost-king-america-lost-legend/. 15 May 2015.

- ^ Lenny Kravitz @LK, “BB, anyone could play a thousand notes and never say what you said in one, #RIP #BBKing,” Twitter, May 15, 2015, 1:46 A. M., https://twitter.com/lennykravitz/status/599103555841040384.