Baba Asante Nalls and Carolina Whitfield Smith participated in the Mississippi Arts Commission’s 2019-2020 Folk Arts Apprenticeship Program. This grants program supports the survival and continued evolution of community-based traditional art forms. During the apprenticeship, the master artist teaches specific skills, techniques and cultural knowledge to the apprentice, who is an emerging artist of the same tradition. Participants are awarded $2,000 to assist with the teaching fees for the master artist and other expenses such as travel costs and supplies. To learn more about the program, click here.

Introduction

Apprentice Carolina Whitfield-Smith had been learning traditional African drum techniques from Master drummer Newman “Baba Asante” Nalls for several years before their apprenticeship began. Through the apprenticeship program, Baba Asante taught Carolina more advanced drumming techniques, and taught her the Dudunba family of drums, which can be more challenging.

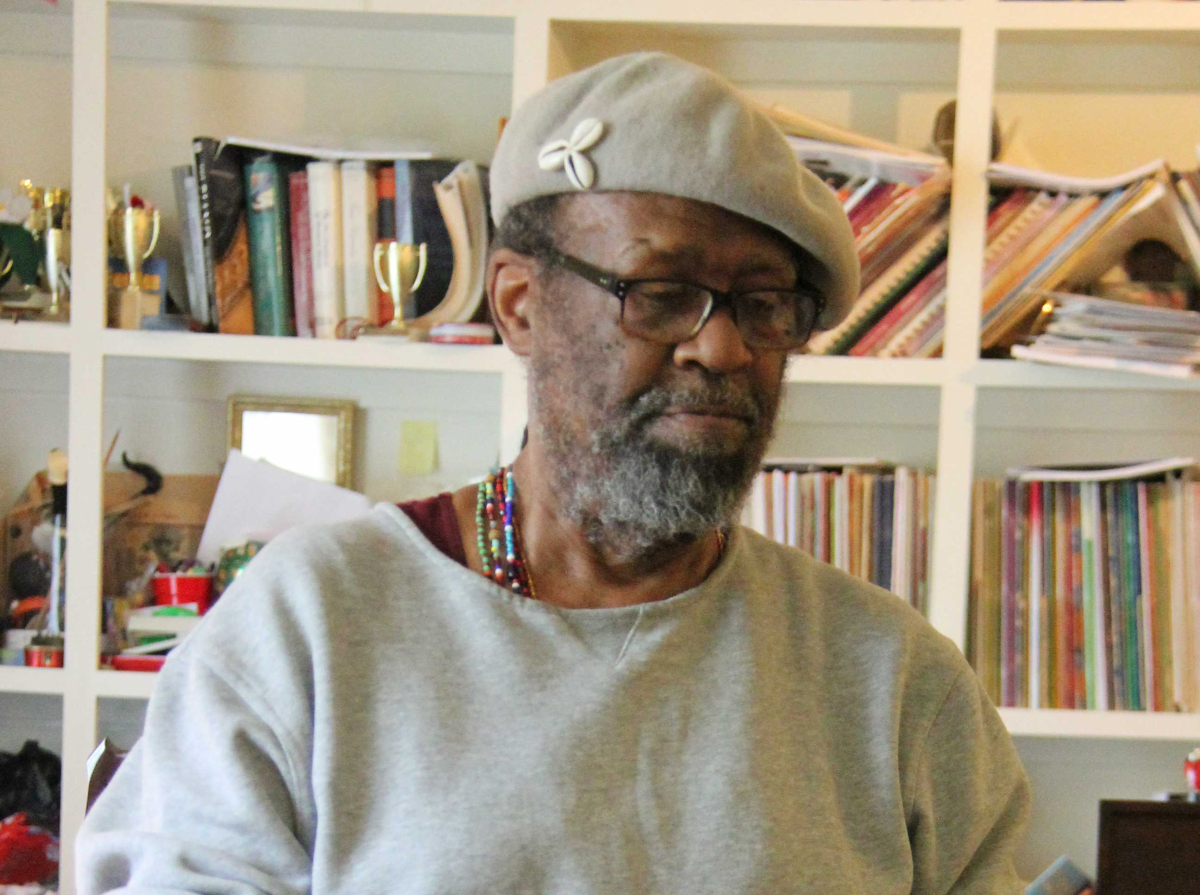

Master Artist: Baba Asante

African drumming is dance music, and the two art forms typically go hand in hand, with each dance having its own meaning.

Newman “Baba Asante” Nalls is originally from the San Fernando Valley in California and has been a musician since the age of nine, playing the clarinet and drums throughout high school. It was not until later in life and after a hiatus from music while he attended college and graduate school that he first became interested in African dance and drum. While living in Chicago, he saw an African dance company perform at a concert. His sons, who were with him at the time, were extremely interested in the combination of dance and music. African drumming is dance music, and the two art forms typically go hand in hand, with each dance having its own meaning. Baba Asante later purchased drums for his sons. In order to help teach them how to play, he started learning the instrument himself. He eventually became immersed in the culture of African drumming and dance and learned to play the Dudunba and Djembe from a community of Senegalese drummers.

Baba Asante felt his work really began when he moved to Mississippi where there was not much of an established African drumming community. His efforts turned to building interest and connecting with other musicians. After living in Jackson for a time, Baba Asante met his apprentice, Carolina, at a wellness retreat where he was teaching drums and where she was practicing tai chi and yoga. After sharing lunch at the same table, their conversation quickly turned to music. Later that evening, Baba Asante asked Carolina to fill in on Dudunba at the drum circle he was leading. Although she had never played before, she thoroughly enjoyed the experience, and she later attended one of Baba Asante’s workshops.

Apprentice: Carolina Whitfield-Smith

Longtime resident of Jackson, Carolina Whitfield-Smith has been playing piano most of her life. She started learning in first grade and eventually became a music major in college. She found that the percussive nature of piano made for an easy transition to the drums. She is drawn to the connection she experiences with the drum when she plays. As she says, “I love the way it feels on your hands. Especially the hand drum, the Djembe.”

Carolina experienced many challenges when first learning, “I guess [it was difficult] in that I’ve never been a very strong player by ear, and this is an oral tradition.” She had a hard time improvising and singing while playing without sheet music, which she was accustomed to on the piano. However, her musical background did give her an advantage over other students in that she was used to right and left hand coordination.

Apprenticeship Experience

Carolina sees her role in this tradition as a practitioner and documentor as she continues to work on tracing Baba Asante’s drumming family tree through generations of drummers.

Baba Asante and Carolina began their apprenticeship after Carolina had attended several of Baba Asante’s workshops. Because Carolina had already become very familiar with the Djembe, they would play a certain song, then Baba Asante would teach her the Dudunba part. Carolina explains the difference between the drums:

“The Djembe is kind of a catch-all term. It’s the one-headed drum that kind of looks like a really nice end table. It’s got kind of a bowl shape and then tapers down to a pedestal shape that flares down toward the bottom. You sit and tilt it between your knees where part of it is resting on the floor, then you play with your hands. Or you can wear it on a strap and walk or dance with it. The Dudunbas are larger, two-headed drums that are the metronome, or the parents of the family, so they’ll keep the main beat of the core. They come in three sizes. The big one is the Dudunba, the middle one is the Songbon, and the small one is the Kinkini. Mine, I got from Baba. When we took his workshop, he let us rent from him. He has a nice collection, and I just loved it so much I just bought it from him.”

During the apprenticeship Carolina wanted to become more proficient on the Dudunba as well as learn how to incorporate more improvisation into the accompaniment. Because she has a hard time learning by ear, she also wanted to begin notating the rhythms in order to preserve the African drum tradition by creating sheet music for the songs. While notating the music was an important aspect of the apprenticeship, so was documenting Baba Asante’s lineage as well as the Senegalese drummers and their mentors, who initially taught Baba Asante in Chicago.

Conclusion

Baba Asante still holds drum circles, which Carolina attends, and he frequently hosts workshops. He explains that the best part of teaching is when he can see his students’ “lights turn on” and he can just tell that they understand the music. At the heart of the apprenticeship and central to Baba Asante’s teaching experience is a continued effort to garner interest in African drumming in the Jackson area. With the apprenticeship over, Carolina now has a deeper understanding of the drums. She has been able to learn and annotate at least 27 songs. She sees her role in this tradition as a practitioner and documentor as she continues to work on tracing Baba Asante’s drumming family tree through generations of drummers.

In the fall of 2020, the Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC) hosted their annual State Arts Conference virtually. During the conference, one artist from each of the five apprenticeship pairs spoke about their apprenticeship experiences and take-aways for a panel facilitated by MAC’s Folk and Traditional Arts Director, Maria Zeringue. In this video, apprentice Carolina Whitfield-Smith talks about the significance of her apprenticeship experience and why it was important for her to participate in the program.