“To include yourself in the future,” he explains, “you have to first learn about your past. And somebody has to go through the trials

before the good can come.”

The civil rights movement of the twentieth century is often lauded as perhaps the most critical, watershed moment to have occurred within American democracy. From out of the margins sprang a generation of men, women, and even children, who would uphold the charge to challenge the perennial hold of white hegemony. If in our assessment, it is axiomatic, that “each generation (in the words of Fanon) must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it,” then the world must bear an especial witness to the role of the artist within this discovery, and also how Bobby Whalen has been fulfilling his generation’s mission for decades.

Whalen is a folk artist from Indianola, Mississippi—a musician and painter who specializes in portraits, murals and hand-lettered signs. Much of Whalen’s art focuses on the southern civil rights movement, Blues music, local history and culture, as well as different experiences that he has had in his life. Through his art, Bobby prides himself as a historian, an important recorder of the human condition. His work comes from his experiences and the rich life that he has led fulfilling many roles as an artist, musician, activist, veteran, teacher and community historian. Talking about his influences and the subject matter of his work, he says: “The only things that we own are our memories.”

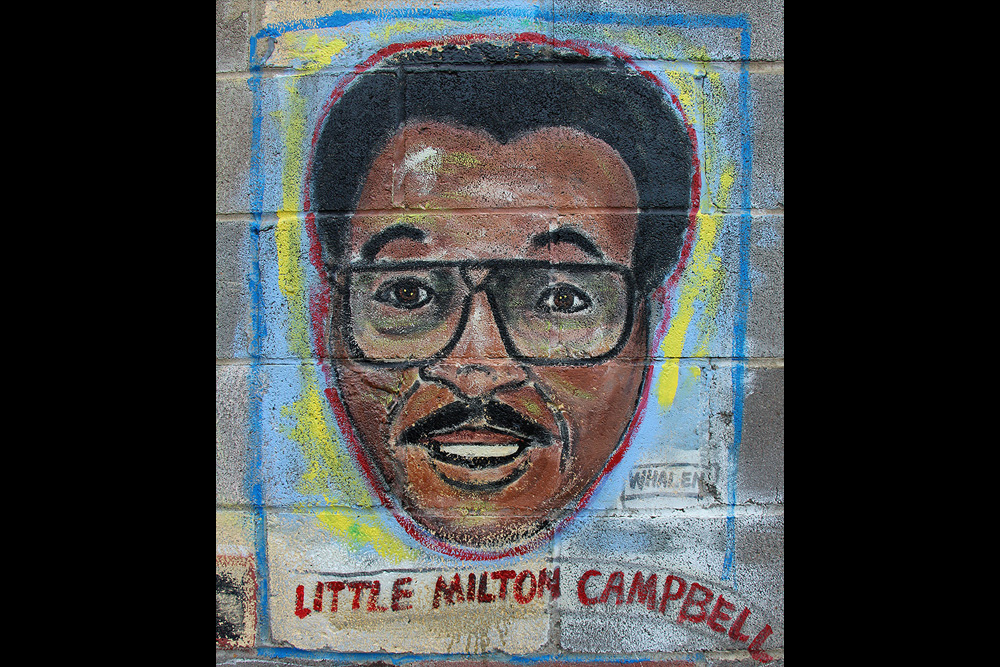

Left: Bobby created this mural of blues musician B.B. King. The mural is located on the side of the Motor Mouse Motorcycle Club building in Indianola. Photos by Maria Zeringue.

As a Blues artist, he has opened for B.B. King and Muddy Waters, both whom he has also painted. He first learned to play music at the age of thirteen and tells the story of how he was able to purchase keyboard lessons after selling the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper, in his community. “My teacher had me starting off with basic stuff like Twinkle-Twinkle Little Star and the fingering chart on a piano,” he laughed. “As soon as she’d leave, I’d go trying to play something by Ray Charles, and she’d come back with a belt.” He would study with his instructor for as long as he could, and soon developed his skill as a drummer by organizing two oil cans and beating on them with sticks. He attributes his love for music to the proliferation of juke joints and local cafes in his neighborhood. He also hints that his passion may be genetic, as his grandfather was rather skilled with a harmonica—all factors that he indicates to be the reason why he took to music “like a duck takes to water.”

It was around the same time that he started learning music that he found his love for visual art and sign painting. Bobby learned how to paint hand-lettered signs when he was 13 from a master sign-painter named Brady Thompson. Through Mr. Thompson’s mentorship, Bobby was able to gain additional income by painting signs in his community. Bobby notes that his sign painting eventually led him to later branch out to painting murals. Today, many of his murals can be seen around Indianola.

As a child, Bobby also loved to draw and paint. He is a self-taught artist who learned by emulating his older brother’s drawings. However, he did not take his painting and drawing work seriously until he enrolled as an art major at Mississippi Valley State. Though originally seeking to study medicine in college, as he was deployed as a medical technician during the war in South Vietnam, he transitioned from studying medicine to art after deciding he needed a profession that would provide a quicker turnaround financially to help support his family. Upon completing his degree, he returned to Indianola to work under a local school principal named Dr. Robert Merritt. It was during this time with Dr. Merritt that Whalen began documenting the fire of the civil rights movement in his work.

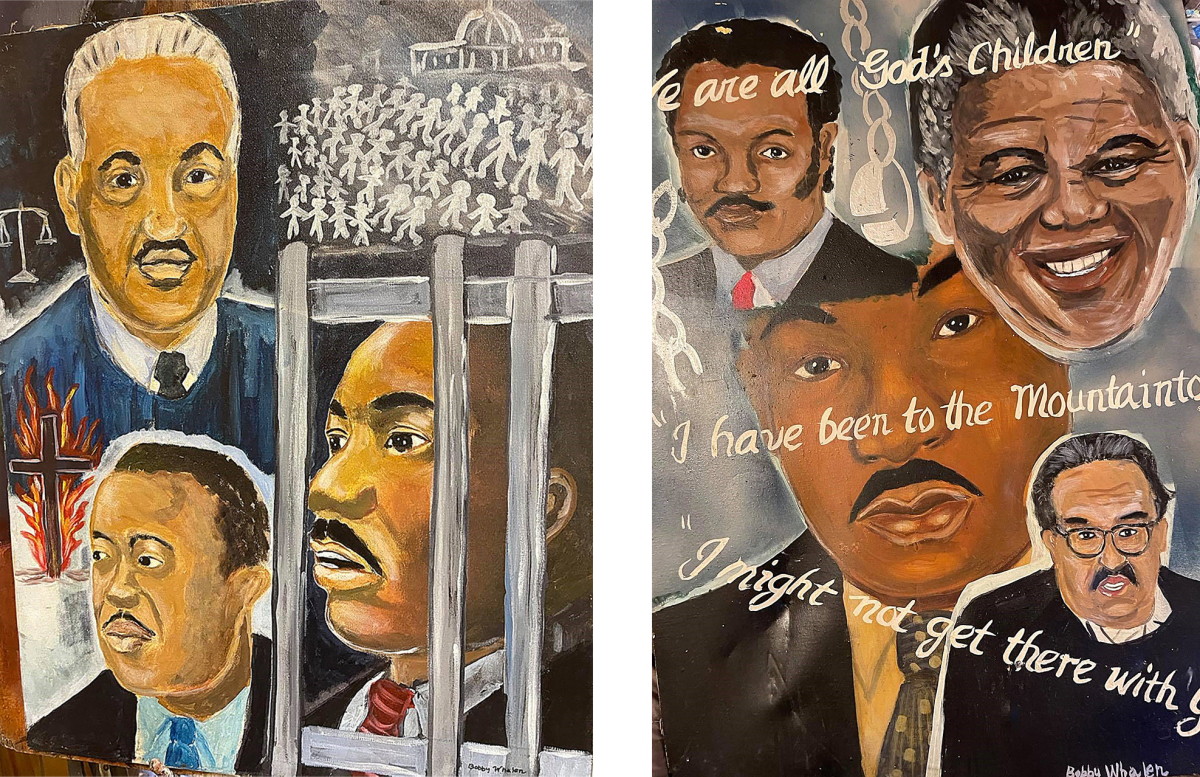

Far right: A painting of Rev. Jesse Jackson, Nelson Mandela, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Thurgood Marshall by Bobby Whalen. Photos courtesy of the artist.

Behind each brush stroke painted and each music note played, there is a story of Bobby’s activism and encounters with leaders of the movement...

Dr. Robert Merritt soared into prominence as an activist during the Indianola struggle, later culminating in his election as the first Black superintendent of the school board in 1986. During the campaign for Dr. Merritt’s election, Whalen was able to meet many civil rights figures, including Muhammad Ali, Stokely Carmichael, Sidney Poitier, and Harry Belafonte. To commemorate Dr. Merritt’s campaign and activism, he painted a 34-foot mural to document the complex and turbulent history of the Movement.

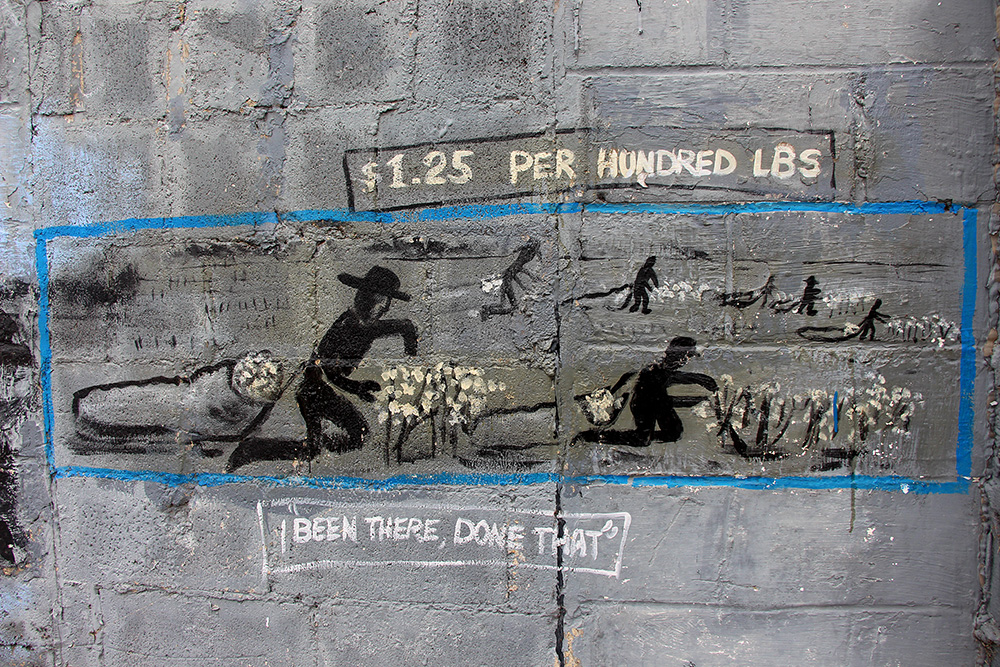

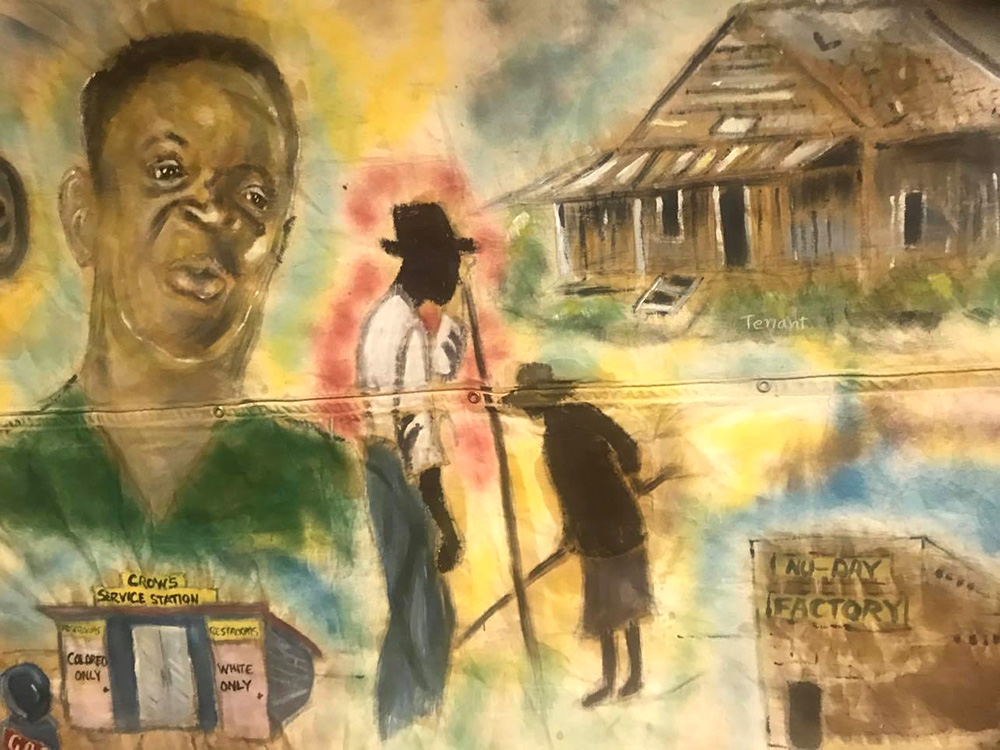

“To include yourself in the future,” he explains, “you have to first learn about your past. And somebody has to go through the trials before the good can come.” The mural is supposed to depict said trials to aid in the instruction of younger generations. For this reason, he hopes to find an institution that will permanently house the piece. When viewing the mural, the audience will notice a montage of various symbols from the struggle. For example, the illustration of “Crow’s Service Station” is set to represent the system of Jim Crow segregation. In further reflection of the day, the service station in the mural has two restrooms, one that is for “Whites Only,” while the other is for “Coloreds Only.” Viewers will also see other images that symbolize less popular memories of the era. An example is the “Nu Day Factory,” scene in this mural, which Whalen says is meant to capture a new factory that was built in Indianola during the 1960s that paid slightly higher wages for much harder work.

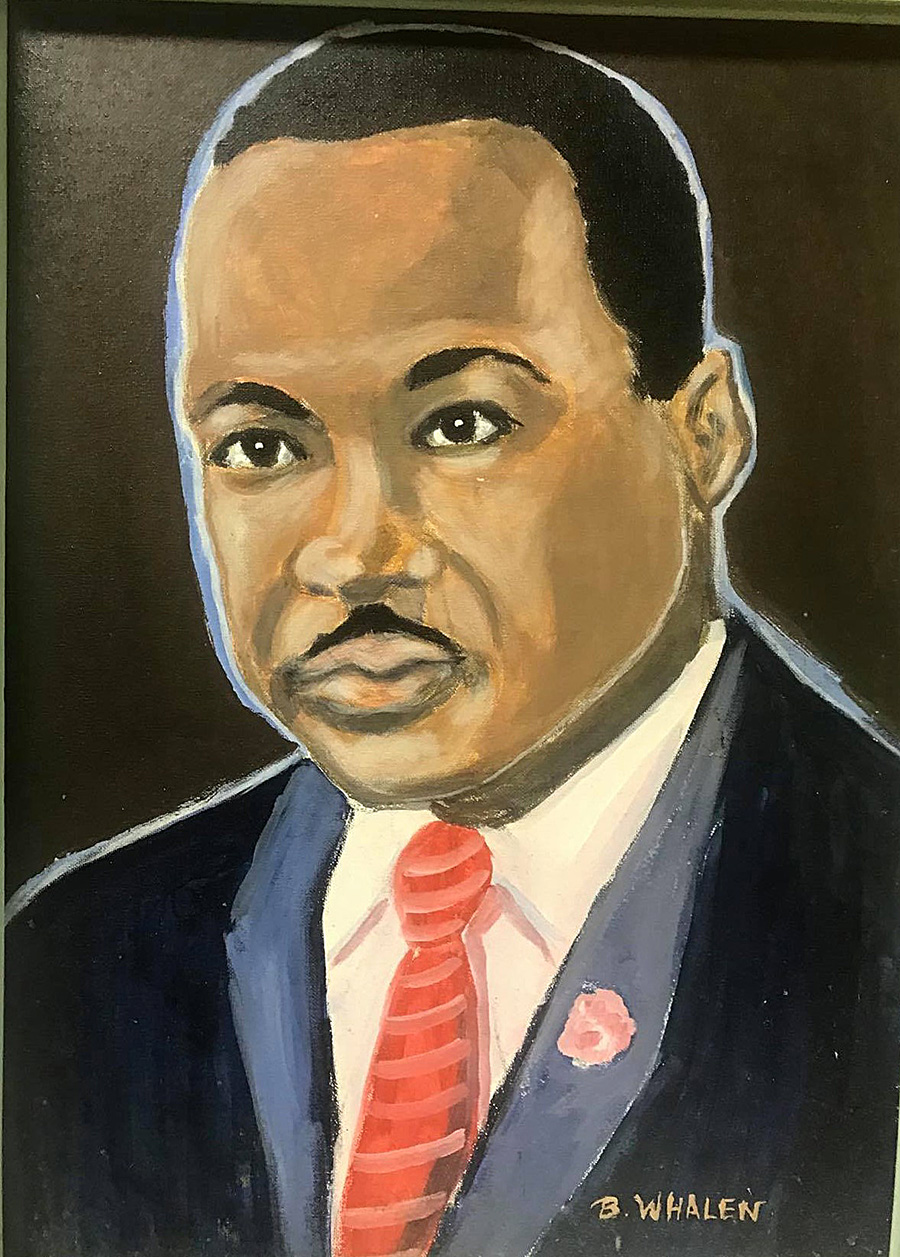

In another painting, the depiction of Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and Thurgood Marshall are used to convey the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Justice. Whalen has also painted several other portraits of significant figures from the era, including Malcolm X, Redd Foxx, Oprah Winfrey, and Muddy Waters. His portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was commissioned by the Lorraine Motel and hung in exhibition for almost two months. With this piece, he recalls how he “tried to put [King’s] respect and dignity in the portrait.”

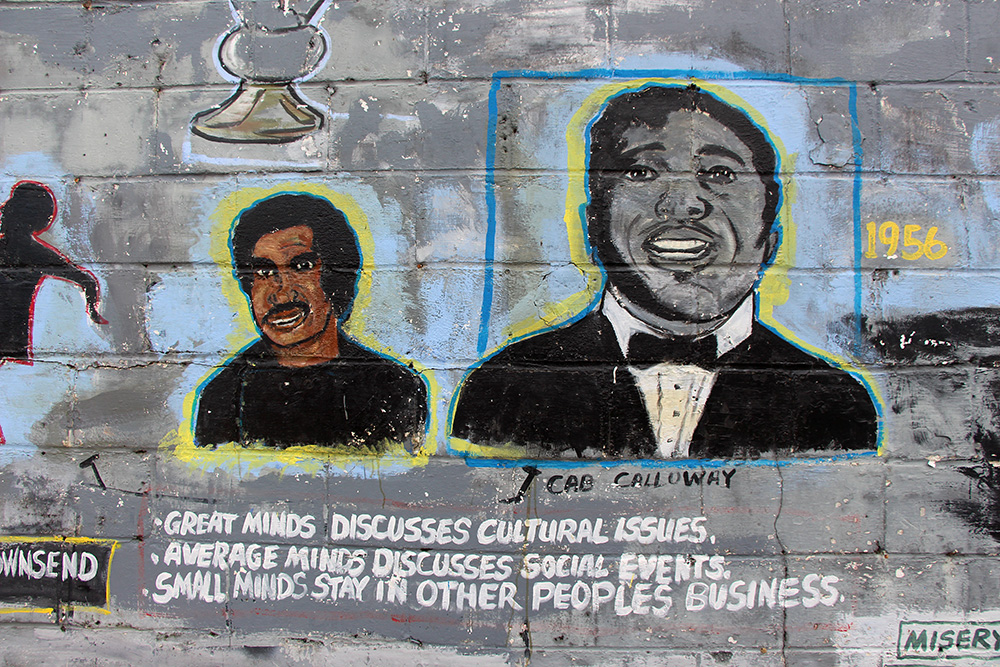

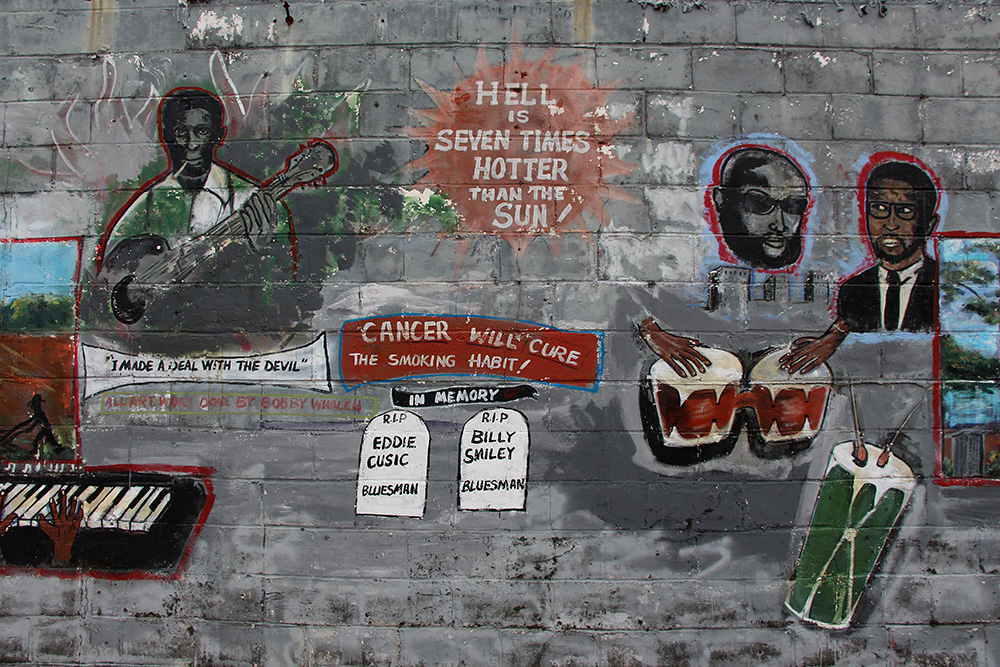

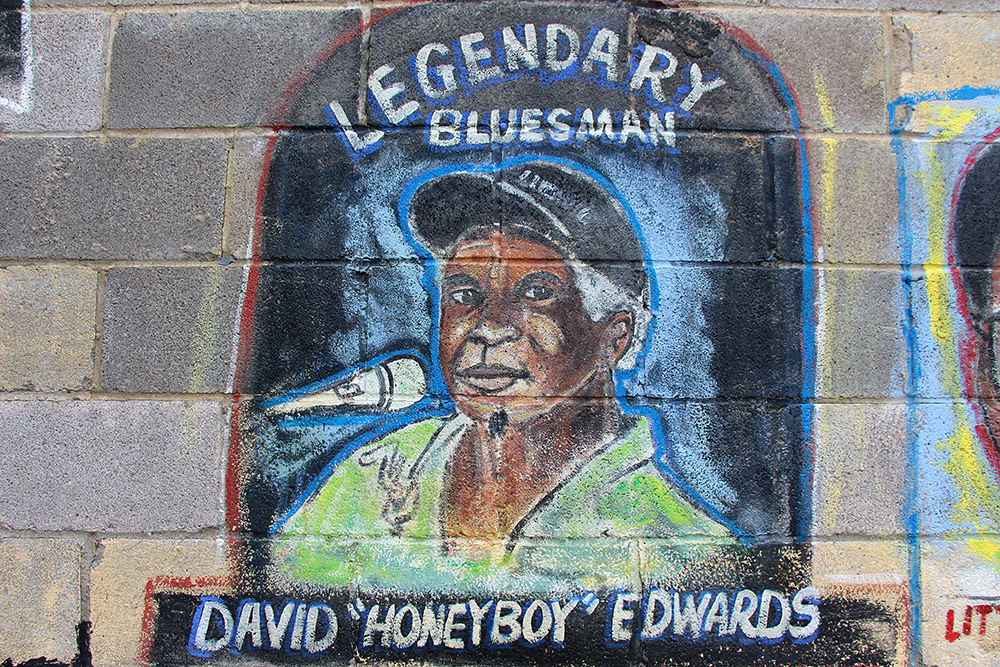

If one were to travel to the Blues Corner Cafe, a fish-fry restaurant owned by Ronnie Ward on Church Street in Indianola, they would see another large mural of which holds Bobby Whalen’s signature. Bobby painted this mural to visualize the history of the Delta region and to memorialize several of the great local musicians who did not receive the recognition many thought they deserved. To commemorate the lives and work of the many musicians who passed through Indianola, Bobby included the names of almost every musician who has ever performed on Church Street, which was the home of a vibrant blues scene during the time of the civil rights movement. To this today, Bobby continues to add names to the list when he has the time. Also depicted in the mural are some of Bobby’s own turns of phrase that he likes to incorporate into his work. He was given the name, the “Church Street Philosopher” due to his use of clever sayings in his signs and murals.

Bobby Whalen’s work has been featured in numerous institutions throughout the south, including the University of Memphis, the University of Florida, the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, and the Mississippi Museum of Art. He even has a day of celebration dedicated to him at his alma-mater. He is also passionate about passing on his skills to the next generation. In 2016, Bobby mentored a fellow sign painter, Calvin Jones through an apprenticeship with the Mississippi Arts Commission. As far as his craft, Whalen says that he is simply a lover of the work: “I’ll probably do it the rest of my life, as long as I got two hands and a sane mind.”

During interviews with Bobby to research this essay, 1 he reminisced on the turbulence of the civil rights era, and even mentions his involvement in many of the marches, to the degree that he was once arrested on a picket line. Behind each brush stroke painted and each music note played, there is a story of Bobby’s activism and encounters with leaders of the movement such as Stokely Carmichael and Fannie Lou Hamer. It is because of experiences such as these that he feels called to participate in and document the history of the civil rights movement in the Delta through his art, a calling that he continues to fulfill today.

“I’ll probably do it the rest of my life,

as long as I got two hands and a sane mind.”

Footnotes

- ^ Source material from this essay was gathered from an interview with Bobby Whalen conducted via telephone by Kumasi McFarland and Maria Zeringue on May 22, 2020 and an interview with Bobby Whalen conducted by Maria Zeringue on October 3, 2017 in Indianola, Mississippi.