Mississippi’s Native American mounds hold many mysteries. If you know what to look for, they appear regularly: tree covered inclines in the midst of neat rows of crops, dotting the Delta landscape. Just north of Greenville on Highway 1, a nearly imperceptible rise marks the beginning of the Winterville mounds. Built on a natural island in the midst of the swamps and backchannels of the Mississippi River, this cluster forms part of a network of mounds surrounding the Mississippi River and its distributaries, which Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) designated as the Mississippi Mound Trail in May 2016.

Each of the 33 sites has a unique story, offering glimpses of the vibrant cultures that once lived throughout the Delta. Today’s Native American Mississippians largely form part of the Choctaw Nation, living in ten counties in the southeastern part of the state. While some of their ancestors likely spent time at Winterville, only tenuous connections exist between today’s tribes and the people who built these mounds between the 12th and 14th centuries.

To me the most interesting parts of the Winterville story are the beginning and the ending, because they’re both mysterious.

I visited the Winterville Mounds on a hot Thursday in July. A group of students from the University of Southern Mississippi worked under a tent where one of the site’s plazas once stood. Archaeologist Ed Jackson leads this ongoing project, which he began in 2005, intending to document the architecture that once stood on mound summits and excavate refuse related to mound use. Several years ago he uncovered evidence of a great feast on one of the mounds with charcoal dates indicating it took place 100 years after archaeologists previously assumed Native Americans abandoned the site. In these discoveries, the story of Winterville continues to evolve. Like other mound sites around the state, what most people know about them comes partly from archaeological research and partly from myth and storytelling.

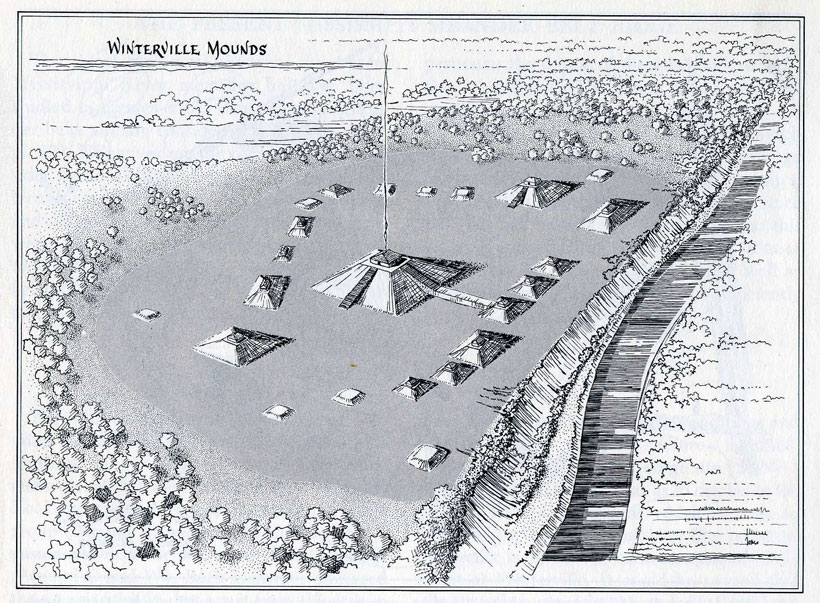

“To me the most interesting parts of the Winterville story are the beginning and the ending, because they’re both mysterious,” says Mark Howell, director of Winterville Mounds Park since 2006. We’re standing inside the site’s museum, which includes displays of pottery, pipes, tools, and other artifacts excavated over the years. A large diagram illustrates the site’s original layout, with at least 23 mounds, two plazas, and clusters of houses extending past the 42 acres now preserved within the state park’s boundaries. “Everything you see at the site is man-made. They made a plan, working on a northwest/southeast axis, and everything sits at an angle,” says Howell.

Howell thinks a theory called lunar standstill may have impacted the site’s design. “A somewhat controversial archaeo-astrologer named William Romaine determined that the three largest mounds here line up with the southern extent of the moon as it makes its way across the horizon, which happens every 18.6 years as a major lunar standstill. We know significant thought and planning went into the site’s design and construction.”

Mound building began in the area with Coles Creek people around 1000 AD, but the site was largely constructed in the 13th century in two generations during the Mississippian era. Another mound complex called Cahokia north of Winterville near present-day St. Louis thrived until around 1250 AD, and some archaeologists theorize that those people moved south to Winterville when construction reached its zenith. “We know there was intense trade between the two sites and that they were both building similar structures,” says Howell.

The sheer amount of physical labor involved in constructing such a site also suggests a powerful, central, authority with the ability to control a large population of workers who lived at Winterville during the mound’s construction. The men and women constructing these ceremonial structures moved dirt with baskets to the site, dumping it out and stamping it flat. The entire site was elevated six feet and then mounds were built on top of this leveled surface, with the tallest mound (Mound A) now standing 55 feet tall. “It’s becoming increasingly probable that each mound was capped with brightly colored clay. You wouldn’t have seen grass on these mounds 1000 years ago; we believe the mounds here would have been bright yellow,” says Howell.

Other sites with a similar design (based around knowledge of lunar standstill) also held burial rituals, and some archaeologists consider the color yellow a mortuary signifier, leading some researchers to conclude Winterville also hosted ceremonies surrounding death. Howell emphasizes that these theories haven’t been proven. “We can’t infer too much. Maybe death rituals were held at Winterville, but most of the interesting theories are a little controversial, and some conservative archaeologists would argue there’s not much here, and that we don’t really know why these mounds were built.”

As Howell explains the site’s construction, a visitor approaches and interrupts. “We’ve got a mound on my grandparent’s land near the Tensas River. Well, it’s part caved in now, but when I was a kid I would dig around in there and find arrowheads and all kinds of things…I’ve got boxes of stuff,” he says.

There’s a wide variety of specimens, and some people are confused. I had one guy who mistook a rusted lawnmower blade for a Spanish sword

Howell nods politely, listening to the man describe artifacts common in the area. A lot of Mississippians (and Louisianans) have mounds on family land, the condition of which varies depending on the land’s history. Some privately owned mounds now make up part of MDAH’s Mississippi Mound Trail, while others have largely disappeared as a result of construction and agriculture. It’s not uncommon for people to have large collections of artifacts about which they are very knowledgeable. “I was completely unprepared for the amount of personal collections,” says Howell. “People feel an intense connection to artifacts that they have found, which is odd because most of their families have been in the area 200 years or less.

At an artifact identification day held in October, nearby residents brought collections to the museum and received expert advice as archaeologists looked through shoeboxes, some full of legitimate artifacts and others full of petrified wood and rocks. “There’s a wide variety of specimens, and some people are confused. I had one guy who mistook a rusted lawnmower blade for a Spanish sword,” says Howell.

Artifacts found on private land belong to the landowner, but artifact removal from state or federal land is illegal. A series of rains in 2015 precipitated a sloughing event on Mound A at Winterville, during which dirt containing artifacts accumulated at the mound’s base. Archaeologists proposed moving the dirt offsite for excavation, initiating conversations between the state and the Mississippi Choctaws, who often serve as the de facto tribal representatives at Winterville and other delta mound sites, because the chiefdoms which ruled the area during the site’s construction no longer exist.

“We think Winterville is probably closer to Chickasaw country, when the Chickasaws were in northern Mississippi. But at various points we have owned most of Mississippi, so anything that is found could be connected to our history,” says Jay Wesley, Director of Cultural Affairs for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw. “Our focus is on honoring Nanih Waiya, which we consider our Mother Mound. We share a history, though, and we do consider mound building part of our sacred culture. When artifacts are found, we think conversations are essential. No one want’s someone coming to their grandmother’s grave and digging things up.”

When [Spanish explorer Hernando] de Soto came through the Delta in the mid-15th century, some forty different named tribes existed. When French Explorer Robert de La Salle followed in his footsteps 150 years later, there were around fifteen “At this point there was political and social upheaval and the Choctaw were taking in refugees. It was like Syria or Libya,” says Howell. “So, is it correct to say the Choctaw built these mounds? No, but it is correct to say that some of their ancestors undoubtedly did. Or maybe not,” he laughs.

“Winterville was part of our land base, and we had a big land base, but our people were all around,” says Wesley. “This whole ownership thing is new to us. Yes different tribes had different agreements about territory, but it was pieces of paper that said, ‘that’s yours’ that led to us losing our land. But this site is a part of our past, regardless of whether it’s specifically Chickasaw or Choctaw.”

Yale archaeologist Jeffrey Brain oversaw excavations at Winterville in 1967 and used charcoal dating to conclude that Native Americans abandoned the site in the early 1500s. For some archaeologists, this meant an unfortunate designation of Winterville as more or less irrelevant, as its settlers didn’t have contact with colonizers. Recent dating indicates that people remained at Winterville much longer. “Ed’s recent excavations have found activity at the site into the 1600s, which means it could be a major polity mentioned in de Soto’s chronicles called Quigualtum. He never went there, but he camped at a site across the river in Lake Village called Guachoya, which is where we believe he is buried, at the bottom of Lake Chicot,” says Howell.

At various points we have owned most of Mississippi, so anything that is found could be connected to our history.

The great feast that Jackson recently excavated at Winterville happened one hundred years after the site was abandoned, meaning that members of what became the Choctaw nation may have taken part. Bones from thousands of swamp rabbits and a large quantity of a plant related to cone flowers were found in one of the smaller mounds. Swamp rabbits are thought to be a totemic animal for the people at Winterville. “They didn’t eat these things in these quantities for no reason. People returned to the area for some sort of ceremony…they remembered this place,” he says.

“People, mostly academics, want to get into the mound and find out what’s in there. They dig things up, or they find things, and then the question becomes: Where does it go? We are adamant that if artifacts are discovered all relevant tribes should be part of that discussion. That’s part of taking back our sacred history,” says Wesley. “Some things can be displayed after a conversation, but Native American culture has been fetishized and sensationalized and in the past that didn’t happen. It used to be normal to have skeletons and remains on display in museums all across the country. We have pieces in Massachusetts and New York.”

You never know what’s in the middle of the mound.

At one point the remains of a Native American man were displayed in Winterville’s museum, removed sometime in the 1970s. When I visited the site a second time, several months later, Howell was working with two college students clearing pottery from the museum’s main display case. Artifacts found in burial mounds were headed to MDAH’s archives in Jackson. “We want to make sure to accommodate any requests from tribes to have remains or artifacts repatriated, and to handle anything found respectfully,” Howell says.

Excavations at the site will continue, with plans to repair Mound A and update and renovate other parts of the park. Howell points to other, smaller, mound sites where an unexpected discovery led to great gains in knowledge about Native American history in the region. The mystery of what’s inside the mounds is part of the site’s appeal, and one that will always remain. There’s still so much to know about Mississippi’s early cultures. Every site is important, particularly a place like Winterville that was a site of power for thousands of years,” Howell says. “You never know what’s in the middle of the mound.”