Bouncing around in that big car, frightened, yet surrounded by love and concern, was the moment that signified Duttoville to young Beauty; his was a community that banded together in the time of trouble.

Beauty’s Duttoville moment changed his life. He was 12, and it was summertime in the late 1960s, which meant endless hours of hanging outside with the neighborhood kids. They were all in someone’s backyard when one of the kids produced a gun, and no sooner than it emerged, it was going off with a deafening blast. In one instant, time and space stood still, and in the next was Beauty’s stunned realization he was hurt and bleeding. The kids took off in two directions, and he stumbled behind his cousins toward a relative’s home.

There was pandemonium, quite like being caught inside a blender. He had been hustled into the house, into a blur of voices and faces, kneeling over him to examine his injury. A bullet had skidded across his jaw. Fortunately, it was lunchtime, and his Uncle Robert, one of the few people in the neighborhood with a car, was home for lunch. They bundled Beauty into the back seat, and one of the neighborhood men, Mr. Simmons, hopped in back with him. As Uncle Robert raced the rutted streets to the hospital, Mr. Simmons soothed him and held a towel to his jaw to staunch the bleeding. Bouncing around in that big car, frightened, yet surrounded by love and concern, was the moment that signified Duttoville to young Beauty; his was a community that banded together in the time of trouble.

Fifty years later, on the eve of the 15th or so, at the Duttoville Neighborhood Reunion, held yearly at the end of July, there is a forum of Duttoville elders: Beauty Carey, a New Orleans resident, who grew up in Duttoville in the 1960s; Mack Henry, who grew up in Duttoville in the 1940s and 1950s and relocated to the Midwest; Rock Jones, who aside from his active military service, has been a life-long resident; Jonathan Hawkins, a life-long resident, and Carey Simmons, Jr., a bluesman’s son and life-long resident as well as the man that held Beauty in his lap with that towel to his jaw. The elders speak on migrations and homecomings, on common roots and connections that don’t die.

Beauty says, “Home is always going to be home to you. You have a good feeling when you pull up and see familiar faces, and you see friends and family and loved ones. That’s part of the quality of your own life.” For him, Duttoville will always be home. He remembers it as a place of industriousness of hands that moved and worked, belonging to people that wanted him to live and thrive.

For him, Duttoville will always be home. He remembers it as a place of industriousness of hands that moved and worked, belonging to people that wanted him to live and thrive.

Duttoville was named for the esteemed priest, Luigi Dutto, who parceled out the land to poor immigrants in the late 1800’s. There, it stood as an independent village, resisting the city of Jackson’s attempts to annex it. According to Jessie Yancy of Mississippi Sideboard, the original Duttoville was bounded on the north by Town Creek, the east by the Pearl River with the Illinois Central and Gulf & Ship Island railroads to the west. Later the village expanded west of the railroad tracks to Terry Road. Others, like the elders, mark its boundaries as anything south of Capitol on Farish Street. In the early 1900’s, after the village was finally annexed by the city, it maintained its original name, which became a pejorative term as the area became more predominantly black and economically disadvantaged. While researching, I came across several alternative spellings for Duttoville, including Doodaville, Doudaville, and Doodleville. One thing that was consistent, though, is the rough, hardscrabble reputation the neighborhood garnered over the years. If you weren’t from there, you didn’t stop there after nightfall, and at one point in time, the police wouldn’t even ride through. If someone was injured, you had to get them to Gallatin Street and Highway 80 for help. In his song, Doodleville Blues, Carey Lee Simmons, Sr. sings: "you better be careful, careful, careful, how you doodle in Doodleville." But really, what seemed dangerous to outsiders was actually a close-knit group of families committed to preserving a way of life that had sustained them during hard times.

When asked what was considered Duttoville to them, they mentioned the streets Factory, Gum, Julienne, Galilee, Nichols, and McCrae, which is pretty much a lane.

“It’s more like a village,” Mack Henry said. “Everyone was family.”

But really, what seemed dangerous to outsiders was actually a close-knit group of families committed to preserving a way of life that had sustained them during hard times.

Mack Henry and Simmons are contemporaries. Though the area was one of unpaved roads and no industry, they recall idyllic times in the 1940s and 1950s. Older neighborhood guys would take them fishing and camping. They would issue challenges: fighting, sports, and over the attentions of young ladies. They would fight and be right back friends again, and nobody got hurt. There were rites of passage: when water used to come up in the ball diamond, they’d go swimming down there. You proved yourself by swimming its length. If you got halfway and somebody had to come get you, you were considered a failure. Back then, Mack Henry’s father headed the semi-pro baseball team. By the time he turned 14, he said his daddy was letting him pitch four innings per game. Reminiscent of the movie, The Bingo Long Travelling All-Stars & Motor Kings, they played teams like the Birmingham Bears, the Indianapolis Clowns, and the Memphis Red Sox. He recalled being the first in the neighborhood to go out for football. A girl named Betty Jo told him that if he went out, he better make first string because they didn’t want no scrubs coming out of Duttoville. He went out and made first string, and the entire neighborhood would come cheer him on.

When they were older, there were good times to be had in the neighborhood jooks. Sugarman, also known as the Cafe, was one such spot. Mr. Ibbs’s was another. Everyone believed Mr. Ibbs had connections in high and low places. People came to play and party at his establishment as if it were a fancy spot, but it was really a hole in the wall complete with dirt floors. Simmons and Mack Henry saw the likes of B.B. King, Bilbo Jenkins, Muddy Waters, and Sonny Boy Williams. Simmons, whose entire family was musical, remembered his father playing there as well.

Says Mack Henry, “On a many night, you would hear that they gone be performing down there [at Ibbs’s], and it’ll cost you a dollar to get in. We’d all dress up and go. That’s the most famous place there is in Jackson.”

They speak on the segregated side of the times as vividly. Mack Henry once worked room service at the King Edward Hotel, a place where he could work but not stay. At the stores on Mill and Capitol, black folk were prohibited to try on clothes, so that they had to guess their size and pay the consequences. They had nice theaters like the Booker T. and the Alamo, but the movies premiered there so late sometimes that they sometimes had to just subject themselves to the peanut gallery 1 at the theater on Capitol Street. Henry didn’t know how bad Duttoville was until he had relocated to Illinois and looked back.

Migrations happened; children grew up and left home. Small family churches dwindled and shuttered. Unlike these gradual transformations, the 1979 Easter flood was an immediate, dramatic change to the physical and emotional landscape of the place.

Migrations happened; children grew up and left home. Small family churches dwindled and shuttered. Unlike these gradual transformations, the 1979 Easter flood was an immediate, dramatic change to the physical and emotional landscape of the place. Every couple of years, the Pearl River would flood Duttoville; the waters would always come, but they’d always go down. Mack Henry remembers he hadn’t been home in a long time when he came in December 1978 to ring in the new year in Jackson. Upon his return to Illinois, he saw some of the worst snows he’d ever experienced. In Jackson, a hard rain began the Thursday before Easter and continued, causing the Pearl River to eventually crest at over 43 feet, more than twice what was then considered flood stage.

According to Stephen Chapman in the New Republic:

To see the worst of what the flood wreaked on Jackson, one has to visit the poorest, blackest section of town, an area in south Jackson known by its inhabitants as Doodleville. Here the houses are stained with mud as high as three and four feet off the ground… Most are used to dealing with such calamities: the Pearl River floods Doodleville every few years, though not as badly as this time.

Rock says, “The flood of 1979 changed Duttoville like night and day. They lost a lot of people.”

Those who could, came back and rebuilt. Those who couldn’t scattered to the wind. The elders agree intervention was needed after the flood but felt like they were ignored, prompting the young people to leave and stay away.

“Not enough people remain here, keeping up the properties,” says Rock. “I hope it won’t always be this way. But I can remember, at one time, for me, I was also kind of ashamed of Duttoville, didn’t claim it, because I was unaware of the sacrifices it took to build it. But now I know that all the things I learned growing up in Duttoville is why I survived so many places in this world.”

In 2019, Duttoville wears a devastated stillness quite similar to that of the lower ninth ward of post-Katrina New Orleans. There are long stretches of lots without homes, and some buildings that lean down rather than stand up. The streets are gutted by potholes. Nearby, the gritty sounds from South Gallatin Street seem to symbolize the progression of time without the once-bustling community. That’s not to say all is lost. Some of the landmarks still stand: Sugarman a.k.a The Cafe. Some of the old families remain. For instance, Mrs. Burleigh, whose home is famous for its Coca-Cola décor, still makes pepper sauce and muscadine jelly, and the Simmons, two of the last children of a bluesman, still make their home in the neighborhood. Hope remains, but unfortunately, hope is less effective than money and action.

Rock says, “The heritage is worth preserving.”

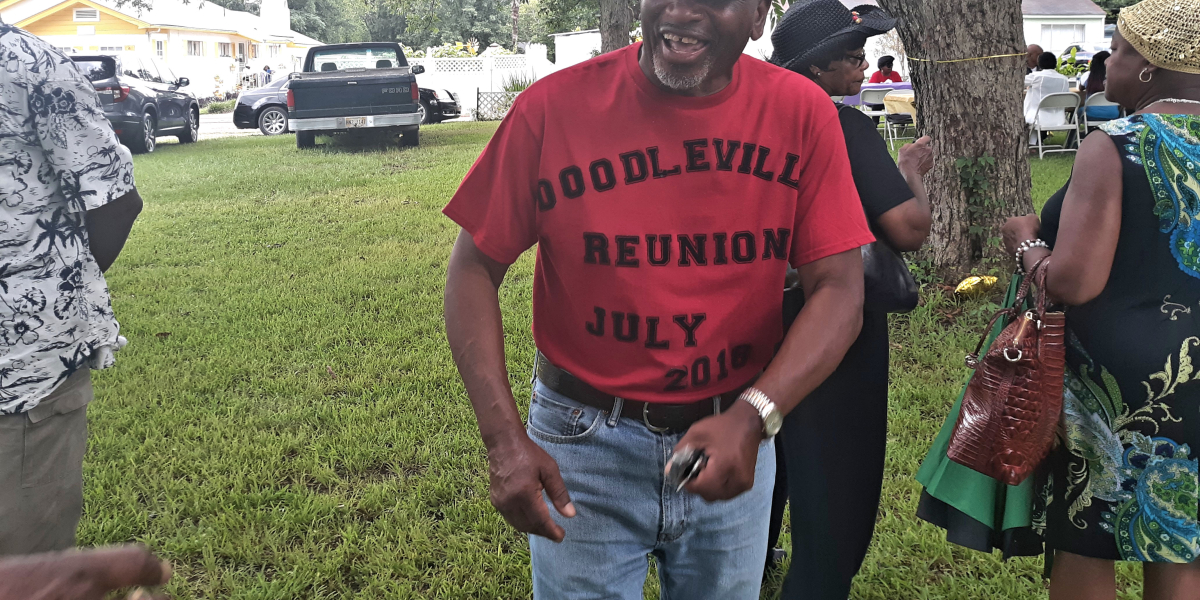

The Annual Neighborhood Reunion is the attempt to do so. On July 20, 2019, Duttoville will set up for a celebration. This gathering, initiated by Duttoville residents, Kenneth O’Quinn and honorary mayor, Pudden Bingham in the mid-90’s, takes place yearly during the third weekend of July. Special t-shirts commemorate each year’s reunion, and wherever there is a bit of grass to set up, the residents erect colorful tents, bbq grills, and huge barrels to fry fish. Around the colorful tents and smoking grills will be a smattering of college students from Jackson State and Tougaloo, and there’ll be younger kids and babies, the grands, great grands, and beyonds of the families who made Duttoville what it was. The elders will be there, too, and they’ll be educating this new generation on their community’s rousing past and still-pertinent heritage. While the blues play on giant sets of speakers, Duttoville congregates, feasts, and fellowships, and they reminisce about the past and pass the old stories along to new ears.

Resources

Projects

John Badham, dir., The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976; Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 1976), 35mm.

Stephen Chapman, "After the 1979 Easter Flood," The New Republic, May 11, 1979.

Footnotes

- ^ Peanut gallery: the cheapest seats in the theater, in the case of the American South at this time, segregated by race.