Since I departed from my former home in Mississippi, the images and stories of the extraordinary built environments found throughout the state have remained burned in my mind, and find themselves frequent jumping off points when talking with someone unacquainted with the state. The joyful reimagining of household objects found in L.V. Hull’s yard show, the visual gospel of Rev. Dennis’ roadside cathedral, the bejeweled Beautiful Holy Jewel Home of Loy Bowlin, the illustrative world of Earl Wayne Simmon’s Art Shop, and the brightly painted characters which lined Mary T Smith’s picket fence--these and other sites mark Mississippi as a catalyst for unorthodox, and often undefinable, forms of expression. Most of the artist-builders featured here passed on before my time in the state, though their personalities, stories, desires, and creative legacies were on full display. Through the people they brought into their fold (many of whom became dedicated believers and advocates), and the remnants left behind in various forms; physical structures that persist to be known despite the cruelties of weather, and through democratic documentation that spans home photo albums, feature films, and academic publications, alike, one can begin to know the fullness of these spaces.

It’s easy to be nostalgic for sites that no longer exist, or aren’t in their “original” form (whatever that means), yet there’s fault in my expectation for a creative work so tied to time and architecture to remain unchanged, particularly once the maker has moved on in this life, or from the work, itself. It is in fact the constantly-shifting, improvisational nature of this style of art that is so powerful: It keeps us all coming back for another glimpse of these artist’s worlds. What I glean from these makers is a loud and clear reminder that living is a constant act of creativity. Often it’s the limitations society places on us (economic status, education, racial and cultural discrimination) that move us to make a world according to our own terms. Each of these sites tell us something important about how Mississippi, and the world, could be.

1. L.V. Hull – L.V. Hull House + Yard, Kosciusko (1942 - 2008)

Miss L.V. Hull was born and raised in McAdams, Mississippi, but made her home in nearby Kosciusko for over 35 years. There, she worked as a caretaker for children in her home and locally, and began to arrange and adorn objects such as shoes, televisions and hubcaps in her house and yard with her signature colorful polka dots and sayings. More than anything, it was the clever folk sayings and phrases she included on her artwork that caught the public's attention — many her original turn of phrase, including:

Face powder may get a man but baking powder will keep him.

I started with nothing, and I still got most of it.

Be aware of the half truth... You may have got ahold of the wrong half.

Hull also painted her own clothing, including the hats she wore. Repurposing beads and baubles of all kinds, she bejeweled objects, and hung shoes among the native plants in her front yard. Hull regularly enjoyed visitors who came from near and far to share in her work, and take home a piece of their own. An L.V. Hull work is not an uncommon site in the homes of Mississippians, each accompanied by a fond anecdote of their visit to Ms. Hull’s house. In addition to her statewide reach, local appreciation never waned, with nearly every storefront on the Kosciusko town square proudly displaying an easily-identifiable piece by their local artist.

When Hull passed away in 2008, her home and collection started deteriorating, but a dedicated group of local friends and advocates of the artist incorporated as the Friends of L.V.. Through the non-profit, the group was able to raise funds to pay off her debts and purchase the land, thereby acquiring the collection altogether. Hull’s collection was then documented, cataloged, and moved from the house and yard to the newly-restored Kosciusko City Hall building for safekeeping. The home was ultimately sold to a neighbor, but the collection remains intact, and ready to be available for public view when the group and the city decide on a suitable way to present and preserve the work and legacy of L.V. Hull.

See:

- To visit the collection in its current holdings, make arrangements with the Kosciusko City Hall.

- Where there is Doubt, Faith: A Case Study in the Community-Based Preservation Efforts of Margaret’s Grocery and the L.V. Hull Home, Jennifer Joy Jameson — A talk given at the Divine Disorder conference at the High Museum of Art, in partnership with the NPS’ National Center for Preservation Technology & Training (2015)

2. Rev. H.D. Dennis – Margaret’s Grocery, Vicksburg (1916 - 2011)

“All are welcome, Jews and Gentiles,” was a phrase often used by Reverend Dennis,” wrote Mary Margaret Miller White. “While many of the sermons he shared with tourists and visitors were hell fire and brimstone, equality and brotherly love were also major themes of his doctrine.” Margaret’s Grocery was a former country store that Rev. Herman D. Dennis turned into his own colorful cathedral located alongside the historic Highway 61 — the Blues Highway — on the outskirts of Vicksburg near the Mississippi River. Reverend Dennis was born in 1916 upriver in Rolling Fork, Mississippi.

His mother died in childbirth and it’s been said that Reverend Dennis can remember being born and watching his mother die. He was raised by an abusive father until he ran away at 12 and was taken in by a white family on a farm between Rolling Fork and Vicksburg. As an adult, he joined the military and served in World War II, where he was first exposed to Freemasons and learned about bricklaying and carpentry — which ultimately became visual, structural, and aesthetic foundations for the site.

Reverend Dennis returned to Mississippi in 1979 and met Margaret Rogers, who ran the roadside country store, Margaret’s Grocery, selling sundries like luncheon meat, cold drinks, and sometimes beer from behind the counter. Miller White wrote that Rev. Dennis told Margaret that if she would marry him, “he would build her a castle that the world would come to see.” It’s been said that Margaret’s Grocery was a sometimes juke joint, though, when Reverend Dennis came on the scene, that quickly ended.

Reverend Dennis then began to transform their single wide mobile home in the early 1980’s. Over the next 30 years, Dennis fashioned towers, archways, fences, paths, and signs, making Margaret’s Grocery a popular attraction far and wide, and one of the most widely documented art environments in the South. A favorite work was the school bus that Dennis adorned and turned into his church, complete with a pulpit at the front of the bus. This is where Reverend Dennis practiced his sermons, both in the solace of God, and in earthly company. The site became known for its bright reds, yellows, and oranges, but it wasn’t until Margaret thought she’d get a little exercise that the pinks started showing up.

In 2009, both Margaret and Reverend Dennis were moved to an assisted living facility. This proved detrimental to the upkeep of Margaret’s Grocery as well as its susceptibility to theft and vandalism, and Margaret soon passed away in 2010. Around this time, local people organized as the Friends of Margaret’s Grocery, organizing town hall meetings and working toward preservation plans. Miller White wrote that “in the spring of 2011, as part of the Mississippi Arts Commission’s annual advocacy initiative Day at the Capitol, Reverend Dennis and Margaret’s Grocery was recognized by then-governor Haley Barbour with a proclamation naming March 20 through 26 Reverend Herman D. Dennis and Margaret’s Grocery Appreciation and Awareness Week. A joint Senate-House resolution was also put in place and state Senator Briggs Hopson and House representative George Flaggs made speeches, kind remarks, and promises to help save Margaret’s Grocery.” While all this momentum seemed promising, local and regional efforts to incorporate as a non-profit and raise funds for preservation lost steam, which was further inhibited by the passing of Reverend Dennis in 2012.

In 2015, Margaret’s Grocery was named one of the 10 Most Endangered Historic Places by the Mississippi Heritage Trust, which became another opportunity for preservation efforts and advocacy. At this point, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History’s Historic Preservation office took on a full survey of the property, in anticipation of potential use in future preservation work.

While the decaying site’s future is still unknown, in 2017, a non-profit was incorporated, and a fundraiser established with the intention of preserving the work and legacy of Rev. Dennis in a new Vicksburg location, yet to be determined. With engagement and direction from the local people who knew and loved the Dennis family, this effort could prove a lasting way to spread the gospel of Reverend Dennis, indeed.

See:

- Home of the Double Headed Eagle — A film by Brian Graves and Ali Colleen Neff (2006)

- God’s Architects — A film by Zack Godshall featuring Rev. Dennis (2009)

- The True Gospel Preached Here — A photography book by Bruce West, University of Mississippi Press (2014)

- Where there is Doubt, Faith: A Case Study in the Community-Based Preservation Efforts of Margaret’s Grocery and the L.V. Hull Home, Jennifer Joy Jameson — A talk given at the Divine Disorder conference at the High Museum of Art, in partnership with the NPS’ National Center for Preservation Technology & Training (2015)

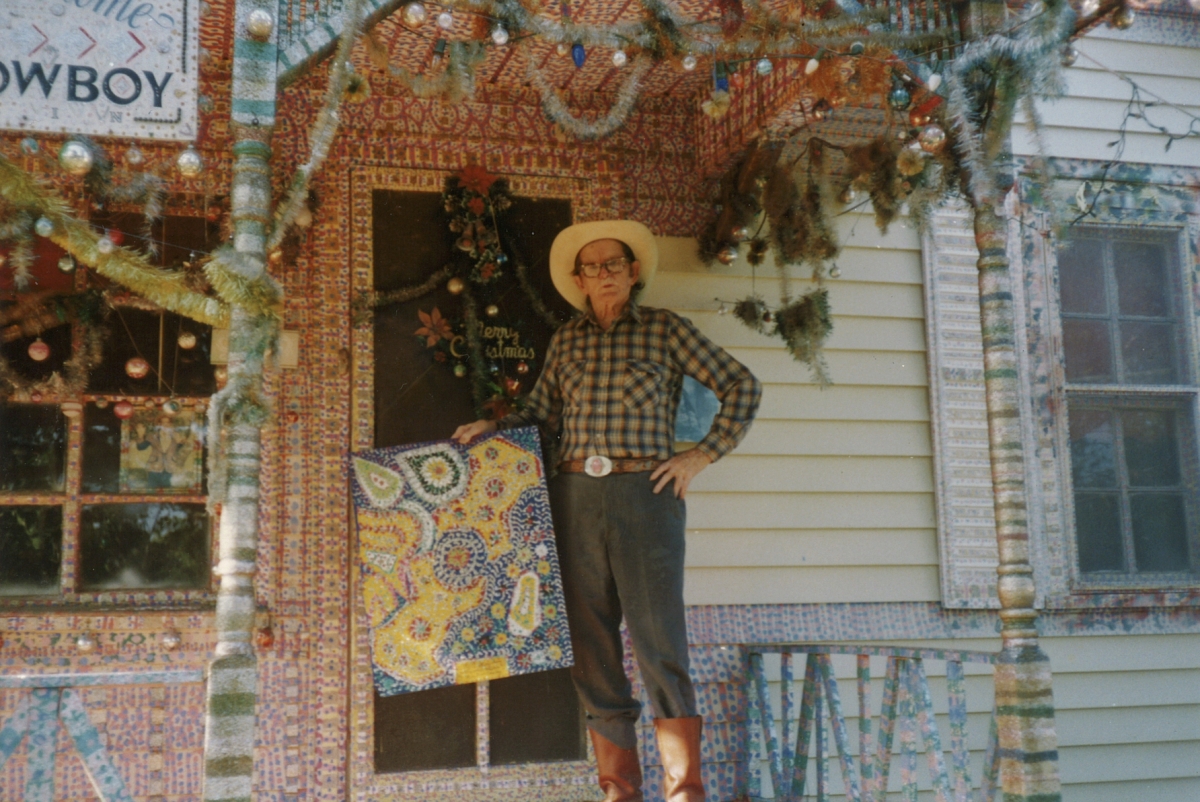

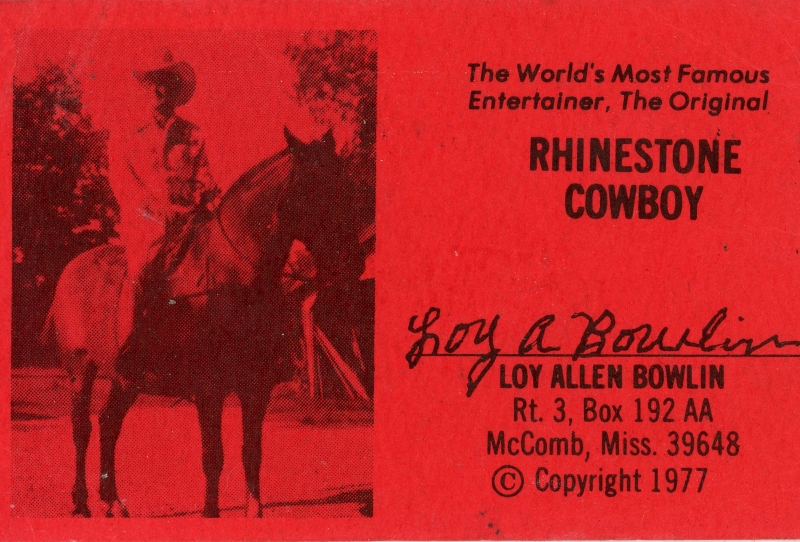

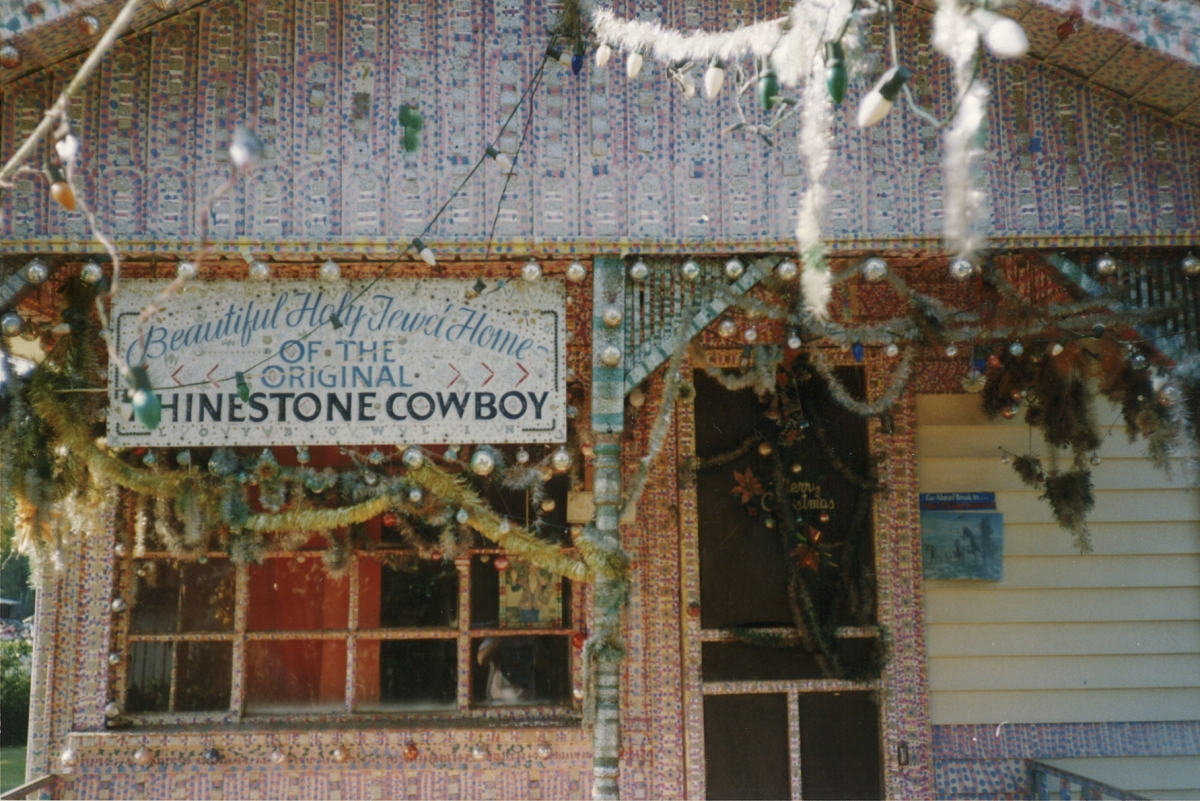

3. Loy Allen Bowlin, "The Original Rhinestone Cowboy" – Beautiful Holy Jewel Home, McComb (1909 - 1995)

Over 20 years have come and gone since the passing of Loy Bowlin and the subsequent removal of his bedazzled magnum opus, the Beautiful Holy Jewel Home, from its location just beyond city limits of McComb, Mississippi. It’s in this small railroad town that the former shade-tree mechanic first embodied the persona and aesthetic of the “Original Rhinestone Cowboy.” Inspired by Glen Campbell’s 1975 hit recording, and, depending on your version of the story—divine intervention—Bowlin was compelled to adorn everything he touched.

Bowlin’s body of work extends from material manifestations like the Home, to his highly adorned Western wear (a gleaming suit for each day of the week), and even rhinestone-studded dentures, to his performance as “The World’s Most Famous Entertainer,” McComb’s buck-dancing, joke-telling, harmonica-toting Rhinestone Man—wheeling around in his personalized 1967 Cadillac, when not a fixture on Main Street McComb.

It was when Bowlin’s health started to decline that he moved away from the public square, and retreated to adorning every inch of his 2 bedroom home off Highway 51, in hopes of bringing his fans and friends directly to him. Bowlin covered his walls with paper cut-outs, glitter, and collaged photographs and magazine clippings, often directed by dreams he would have. The result of the work was nothing but cathedralesque, and visitors would often cite the range of effects from viewing the Home in the light of different times of day. A community of emerging artists, many of them generations younger than Bowlin became steadfast in their loyalty and support of him. A family of visual artists including Paul Maurer and his grown children Christina and Saul Maurer, ran a sign-painting shop and studio, and would often collaborate with the artist, helping to realize Bowlin’s unique vision and identity through contributing hand-lettering on the house and car, and paintings on his customized jackets.

Since the passing of Loy Bowlin in 1995, his creative legacy has largely been explored beyond Mississippi’s borders, with the Beautiful Holy Jewel Home ultimately arriving nearly 1,000 miles away from McComb at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin for conservation and public access. At the museum, Bowlin’s Home, and other works have been cared for, exhibited, and interpreted over the years, bringing national and global into his dazzling world. This year, Bowlin’s Home went on display for the first time in 10 years in a new exhibit I helped with called “The Making of a Dream.” From 2015-2017 I gathered with Bowlin’s family, friends, and collaborators, who generously shared their stories, home photos, clippings, and other objects. For the first time, an exhibition of Bowlin’s artistry is largely interpreted and brought to life by the voices of the Mississippians who knew him, and experienced him best.

Today, a drive past the small plot of land that once held Bowlin’s 2 bedroom home reveals only one clue of its former glory: A small shed with a spray-painted mural that Bowlin commissioned from his friend Paul Maurer, proclaiming the “Rhinestone Cowboy” brand. But if you ask any local person over the age of 30, they’re likely to offer an anecdote or two of Rhinestone’s brave and compelling example of rural, Southern creativity. They say it sticks with you.

See:

- Wild Wheels — A film by Harrod Blank (1992)

- Loy Bowlin (1909-1995): The Road to My Horizon — An article by Leslie Umberger in Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds (Princeton Architectural Press and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 2007)

- THE MAKING OF A DREAM: Loy Bowlin + Jennifer Joy Jameson — An exhibition at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (2017-2019)

- Audio Stories from THE MAKING OF A DREAM exhibition — produced by JJJ (2017)

4. Earl Wayne Simmons – Earl’s Art Shop, Bovina (b. 1956)

Up the road from Margaret’s Grocery was Earl’s Art Shop in small town Bovina. As a child, Earl Wayne Simmons made toy jukeboxes, trucks, and planes out of cardboard and bottle caps. With an early interest in becoming an artist, he found creative ways to continue building sculptural works when he trained as a carpenter in the Job Corps in Louisville, Kentucky.

When Simmons returned to Bovina in 1978, he decided to build out his home into a studio, cafe and eventually a gallery shop, where he could welcome guests to break bread, enjoy his artwork, and occasionally juke it up on his Wurlitzer, which was loaded with 45s. Many of Simmons works were larger than life, like a giant carton of Kool cigarettes that was recently exhibited in the Gasperi Collection at New Orlean’s Ogden Museum of Southern Art. His work has been widely collected and represented in the South, primarily with the advocacy of Vicksburg’s Attic Gallery, and Southside Gallery in Oxford.

In 1994, Simmons received an Artist Fellowship from the Mississippi Arts Commission, which he used to expand the Art Shop, which resulted in a total of 30 separate rooms. Curator Katherine Huntoon writes, “Over the remainder of the decade, he focused primarily on painting, taking as his subject matter such Mississippi pop culture icons as hot tamales, juke joints, and Highway 61, and often riffing on advertising images.”

Tragically, Earl’s Art Shop burned to the ground in 2002, after which he rebuilt the site, only to endure another fire in 2012. Earl has largely shifted to making new works outdoors, which then make their way to the Attic Gallery for public view, though, as of 2015, Earl started the process of rebuilding his beloved Art Shop once more.

See:

- A Helping of Gravy: Earl’s Art Shop and Cafe by Lindsay Kate Reynolds, Southern Foodways Alliance (2015)

- Earl Simmons by Katherine Huntoon in the Mississippi Encyclopedia, University of Mississippi Press (2017)

What I glean from these makers is a loud and clear reminder that living is a constant act of creativity.

5. Mary T. Smith – Yard Show, Hazlehurst (1904 - 1995)

One of the relatively few female artists known for building an art environment, Mary Tillman Smith made her expression known in bold figurative stories told in her Hazlehurst yard show. Born into a sharecropping family in Southern Mississippi, educational resources and opportunities were limited, and the severe hearing loss she was born with made it difficult to communicate with her family and peers. Although her voice was routinely subjugated, Ms. Smith made her experiences and perspective known in full color.

Houston gallerist Jay Wehnert explains the personal history that motivated the artist:

As a teen, she married Gus Williams, a union that lasted just two months due to her new husband’s infidelity and her uncompromising refusal to accept it. Now a young divorced woman, Mary worked and lived independently from her family. She soon met John Smith, a sharecropper, and they married. Together, they raised potatoes and peanuts. However, their lives together would also be disrupted by a controversy not of Mary’s making, but again, of her principles. As a sharecropper, John Smith worked his farm and was given an end-of-year settlement by the landlord based on the farm’s production. Mary Smith kept careful farm records and her calculations did not agree with the landlord’s meager assessment. In the dispute that ensued, the landlord ordered John Smith to get rid of his wife if he wanted to continue working the farm. Smith agreed, sent Mary packing, and took on a new “wife” provided by the landlord. Mary left for nearby town of Hazelhurst, which would be her new home. These events in Mary Smith’s life as a young woman, in a time and culture that almost required her to have a husband for economic and social survival, paint a picture of a woman who was fiercely independent and willing to risk all for her integrity. Mary Smith settled in Hazlehurst and worked as a domestic. She raised a son, fathered by a man that she did not marry, but maintained a close relationship with. She was deeply religious and was actively engaged with her faith and church.

Starting in her 70s, Ms. Smith started making use of the dump near her home on Highway 51, salvaging wood and sheets of corrugated tin to create paintings that were then arranged carefully along her fence and outdoor structures for all to see. Self-portraits, neighbors, animals, and biblical scenes made a moving tapestry of narrative presented by the artist, often including striking messages such as “I Know You. Hear I Am” or “I Was in a Rake. The Lord Was For Me.” Ms. Smith created work through the 1980s until she had a stroke that slowed her practice until she passed away in 1995. Although Mary T. Smith’s ever-changing yard show does not stand along Highway 51 (barely north of Loy Bowlin’s site in McComb), her work has been introduced to global audiences in the collections of Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, New York’s American Folk Art Museum, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, alike. Smith’s artwork continues to be a benchmark in Mississippi visual arts, and her voice amplified by her lasting creative legacy.

See:

- Mary T. Smith, Her Name is Someone by William Arnett. Souls Grown Deep Foundation

Other Mississippi sites, both gone and remaining:

- William Carl Middleton - Bottle House, Flowood (non-extant)

- Wesley Bobo - Giant metal figures, Vicksburg (extant)

- Walter Harvell Jackson and Pelleree Jackson - Palestine Gardens, Lucedale (extant)